Άκρο κεφαλόποδου

Το άκρο κεφαλόποδου είναι ευέλικτο μυώδες όργανο που προσφύεται κοντά στο κεφάλι του και γύρω από το ράμφος του, λειτουργεί ως μυϊκός υδροστάτης, και μπορεί να ονομάζεται είναι βραχίονας, πόδι ή πλοκάμι.[A]

Περιγραφή

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Στην επιστημονική βιβλιογραφία, το άκρο κεφαλόποδου διαφοροποιείται από το πλοκάμι, αν και οι όροι συχνά θεωρούνται συνώνυμοι. Γενικά, ο βραχίονας έχει μυζητήρες σχεδόν σε όλο το μήκος του, ενώ το πλοκάμι έχει μυζητήρες μόνο προς το τέλος.[4] Εκτός ορισμένων εξαιρέσεων, τα χταπόδια έχουν οκτώ βραχίονες και 0 πλοκάμια, ενώ τα καλαμάρια και οι σουπιές έχουν οκτώ βραχίονες και δύο πλοκάμια.[5] Τα άκρα των ναυτιλοειδών, που είναι περίπου 90 και δεν έχουν μυζητήρες, ονομάζονται πλοκάμια.[6][7]

Τα πλοκάμια των Δεκαποδιμόρφων πιστεύεται ότι προέρχονται από το τέταρτο ζευγάρι βραχιόνων των προγονικών κολεοιδών, αλλά ο όρος βραχίονες IV αναφέρεται στο επόμενο, κοιλιακό ζευγάρι βραχίονων στο σύγχρονα ζώα (που είναι εξελικτικά το πέμπτο ζευγάρι).

Τα αρσενικά κεφαλόποδα διαθέτουν ένα εξειδικευμένο άκρο για την απόθεση σπέρματος παράδοση, το εκτοκότυλο.

Ανατομικά, τα άκρα των κεφαλόποδων βασίζονται σε χιαστή δομή ελικοειδών ινών κολλαγόνου αντίθετα προς την εσωτερική μυϊκή υδροστατική πίεση.[8]

Μυζητήρες

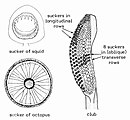

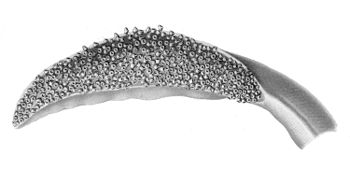

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Οι βραχίονες ή πόδια κεφαλόποδων έχουν πολλούς μυζητήρες σε όλο το μήκος της κοιλιακής επιφάνειας, όπως φαίνεται από παρατήρηση χταποδιού, καλαμαριού και σουπιάς. Τα πλοκάμια κεφαλόποδων διαθέτουν μυζητήρες ομαδοποιημένους σε συστοιχίες στα διευρυμένα σαν παλάμες άκρα τους, όπως φαίνεται από παρατήρηση ορισμένων ειδών καλαμαριού και σουπιάς.[9] Ο μυζητήρας είναι συνήθως κυκλικός και κοίλος και διακρίνεται σε δύο μέρη: μία εξωτερική ρηχή κοιλότητα που ονομάζεται infundibulum και μία κεντρική κοιλότητα που ονομάζεται κοτύλης. Και οι δύο αυτές δομές είναι παχυλοί μύες, και καλύπτονται με προστατευτική στιβάδα χιτίνης .[10] Οι μυζητήρες λειτουργούν συνεργικά με τα άκρα του κεφαλόποδου για αφή, για σύλληψη της λείας και για μετακίνηση. Όταν ένας μυζητήρας αγγίζει ένα αντικείμενο, το infundibulum κυρίως παρέχει πρόσφυση, ενώ η κοτύλη παραμένει ελεύθερη. Η σύνδεση και αποσύνδεση επιτυγχάνονται με διαδοχική συστολή των μυών του infundibulum και της κοτύλης.[11][12]

-

Βραχίονες και στοματική μάζα στο καλαμάρι Taningia danae. Όπως όλα τα Octopoteuthidae τα ενήλικα ζώα δεν έχουν πλοκάμια

-

Η στοματική περιοχή του καλαμαριού Semirossia tenera

-

Κεφάλι και άκρα του καλαμαριού Rossia glaucopis

-

Η στοματική περιοχή αρσενικού Bathypolypus arcticus με εκτοκότυλο στον τρίτο βραχίονα (αριστερά)

-

Μυζητήρες κεφαλόποδου και διάταξη των μυζητήρων στην παλάμη.

-

Σειρά από μυζητήρες σε γιγάντιο καλαμάρι.

-

Πόδι χταποδιού με δύο σειρές από μυζητήρες

-

Μυζητήρες χταποδιού

-

Μεταλλαγμένοι μυζητήρες χταποδιού

Ανωμαλίες

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Έχουν καταγραφεί πολλά περίεργα άκρα χταποδιών,[13][14] , όπως ένα 6-ποδο χταπόδι (με το παρατσούκλι Ερρίκος ο Hexapus), 7 ποδο χταπόδι,[15] 10 ποδο Χταπόδι briareus,[16] με ένα άκρο πηρούνι,[17] χταπόδια με διπλό ή διμερείς εκτοκότυλους,[18][19] και δείγματα με έως και 96 παρακλάδια άκρου.[20][21][22]

Παρόμοιες ανωμαλίες άκρων έχουν καταγραφεί σε σουπιές,[23] καλαμάρια,[24] και bobtail καλαμάρια.[25]

Μεταβλητότητα

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Τα άκρα και οι μυζητήρες κεφαλόποδων διαφέρουν ως προς τις μορφές και μάλιστα σημαντικά μεταξύ των ειδών. Μερικά παραδείγματα παρουσιάζονται παρακάτω.

Βραχίονες

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Για εκτοκότυλα δείτε εκτοκοτυλική μεταβλητότητα.

| Το σχήμα του βραχίονα | Είδη | Οικογένεια |

|---|---|---|

|

Todarodes pacificus | Ommastrephidae |

Πλοκάμια

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]| Το άκρο του πλοκαμιού | Είδη | Οικογένεια |

|---|---|---|

|

Abraliopsis morisi | Enoploteuthidae |

|

Ancistroteuthis lichtensteini | Onychoteuthidae |

|

Architeuthis sp. | Architeuthidae |

|

Austrorossia mastigophora | Sepiolidae |

|

Berryteuthis magister | Gonatidae |

|

Idioteuthis cordiformis | Mastigoteuthidae |

|

Iridoteuthis iris | Sepiolidae |

|

Mastigoteuthis glaukopis | Mastigoteuthidae |

|

Onykia ingens | Onychoteuthidae |

|

Semirossia tenera | Sepiolidae |

|

Spirula spirula | Spirulidae |

|

Todarodes pacificus | Ommastrephidae |

Μυζητήρες

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Βιβλιογραφία

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Σημειώσεις

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]- ↑ A study has determined that octopi have two arms and six legs, often commonly and erroneously referred to as "tentacles". [1] Another study found that there is a functional difference in the way the appendages are used for task division. "These findings give evidence for limb-specialization in an animal whose 8 arms were believed to be equipotential."[2] The two rear appendages are generally used to walk on the sea floor, while the other six are used to forage for food.[3]

Παραπομπές

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]- ↑ Thomas, David (12 August 2008). «Octopuses have two legs and six arms». The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/2547597/Octopuses-have-two-legs-and-six-arms.html. Ανακτήθηκε στις 30 July 2018. «To most of us it has always seemed obvious that an octopus has eight arms. Octopuses have two legs and six arms Claire Little, a marine expert from the Weymouth Sea Life Centre in Dorset, said: 'We've found that octopuses effectively have six arms and two legs.'»

- ↑ Ruth A., Byrne; Kuba, Michael J.; Meisel, Daniela V.; Griebel, Ulrike; Mather, Jennifer A. (August 2006). «Does Octopus vulgaris have preferred arms?». Journal of Comparative Psychology (American Psychological Association) 120 (3): 198-204. http://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2006-09888-005. Ανακτήθηκε στις July 30, 2018.

- ↑ Lloyd, John· Mitchinson, John (2010). QI: The Second Book of General Ignorance. London: Faber and Faber. σελ. 3. ISBN 0571273750.

As result, marine biologists tend to refer to them as animals with two legs and six arms.

- ↑ Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold 1999. Cephalopoda Glossary Αρχειοθετήθηκε 2018-07-06 στο Wayback Machine.. Tree of Life web project.

- ↑ Norman, M. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 15. "There is some confusion around the terms arms versus tentacles. The numerous limbs of nautiluses are called tentacles. The ring of eight limbs around the mouth in cuttlefish, squids and octopuses are called arms. Cuttlefish and squid also have a pair of specialised limbs attached between the bases of the third and fourth arm pairs [...]. These are known as feeding tentacles and are used to shoot out and grab prey."

- ↑ Fukuda, Y. 1987. Histology of the long digital tentacles. In: W.B. Saunders & N.H. Landman (eds.) Nautilus: The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil. Springer Netherlands. pp. 249–256. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_17

- ↑ Kier, W.M. 1987. «The functional morphology of the tentacle musculature of Nautilus pompilius» (PDF). Αρχειοθετήθηκε από το πρωτότυπο (PDF) στις 17 Ιουνίου 2010. Ανακτήθηκε στις 31 Ιουλίου 2018. In: W.B. Saunders & N.H. Landman (eds.) Nautilus: The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil. Springer Netherlands. pp. 257–269. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3299-7_18

- ↑ Inside natures giants, Giant squid episode.

- ↑ von Byern J, Klepal W (2005). «Adhesive mechanisms in cephalopods: a review». Biofouling 22 (5–6): 329–38. doi:. PMID 17110356.

- ↑ Walla G (2007). «A study of the Comparative Morphology of Cephalopod Armature». tonmo.com. Deep Intuition, LLC. Ανακτήθηκε στις 8 Ιουνίου 2013.

- ↑ Kier WM, Smith AM (2002). «The structure and adhesive mechanism of octopus suckers». Integr Comp Biol 42 (6): 1146–1153. doi:. PMID 21680399. https://archive.org/details/sim_integrative-and-comparative-biology_2002-12_42_6/page/1146.

- ↑ Octopuses & Relatives. «Learn about octopuses & relatives: locomotion». asnailsodyssey.com. Αρχειοθετήθηκε από το πρωτότυπο στις 22 Μαΐου 2013. Ανακτήθηκε στις 8 Ιουνίου 2013.

- ↑ Kumph H.E. (1960). «Arm abnormality in octopus». Nature 185 (4709): 334–335. doi:.

- ↑ Toll R.B., Binger L.C. (1991). «Arm anomalies: cases of supernumerary development and bilateral agenesis of arm pairs in Octopoda (Mollusca, Cephalopoda)». Zoomorphology 110 (6): 313–316. doi:. https://archive.org/details/sim_zoomorphology_1991-08_110_6/page/313.

- ↑ Gleadall I.G. (1989). «An octopus with only seven arms: anatomical details». Journal of Molluscan Studies 55 (4): 479–487. doi:. http://mollus.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/55/4/479.

- ↑ Minor birth defect resulting in 10-armed juvenile, all arms fully present and functional.[νεκρός σύνδεσμος] CephBase.

- ↑ Minor birth defect showing bifurcated arm tip. Both tips were fully functional.[νεκρός σύνδεσμος] CephBase.

- ↑ Robson G.C. (1929). «On a case of bilateral hectocotylization in Octopus rugosus». Journal of Zoology 99 (1): 95–97. doi:.

- ↑ Palacio, F.J. 1973. «On the double hectocotylization of octopods». The Nautilus 87: 99–102.

- ↑ Okada Y.K. (1965). «On Japanese octopuses with branched arms, with special reference to their captures from 1884 to 1964». Proceedings of the Japan Academy 41 (7): 618–623. http://www.journalarchive.jst.go.jp/english/jnlabstract_en.php?cdjournal=pjab1945&cdvol=41&noissue=7&startpage=618.[νεκρός σύνδεσμος]

- ↑ Okada Y.K. (1965). «Rules of arm-branching in Japanese octopuses with branched arms». Proceedings of the Japan Academy 41 (7): 624–629. http://www.journalarchive.jst.go.jp/english/jnlabstract_en.php?cdjournal=pjab1945&cdvol=41&noissue=7&startpage=624.[νεκρός σύνδεσμος]

- ↑ Monster octopi with scores of extra tentacles. Pink Tentacle, July 18, 2008.

- ↑ Okada Y.K. (1937). «An occurrence of branched arms in the decapod cephalopod, Sepia esculenta Hoyle». Annotated Zoology of Japan 17: 93–94.

- ↑ Bradbury H.E., Aldrich F.A. (1971). «The occurrence of morphological abnormalities in the oegopsid squid Illex illecebrosus (Lesueur, 1821)». Canadian Journal of Zoology 49 (3): 377–379. doi:.

- ↑ Voss G.L. (1957). «Observations on abnormal growth of the arms and tentacles in the squid genus Rossia». The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 20 (2): 129–132.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||