Χρήστης:Irotab

| Ο χρήστης συμμετέχει σε δραστηριότητα μετάφρασης λημμάτων, ως φοιτητής του τμήματος Μαθηματικών του ΑΠΘ (πληροφορίες). Ο Α.Μ. του είναι 15033. |

Βιογραφία

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Πρώτα χρόνια

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]Ο Γκότφριντ Λάιμπνιτς γεννήθηκε στις 1 Ιουλίου του 1646, προς το τέλος του Τριακονταετούς Πολέμου, στη Λειψία, Εκλογικό Σώμα της Σαξονίας, από τον Friedrich Leibniz και τη Catharina Schmuck.Ο Friedrich επισήμανε στο οικογενειαό ημερολόγιο:

- "21. Juny am Sontag 1646 Ist mein Sohn Gottfried Wilhelm, post sextam vespertinam 1/4 uff 7 uhr abents zur welt gebohren, im Wassermann."

Στα Ελληνικά:

- "Την Κυριακή στις 21 Ιουνίου [NS: 1 July] 1646, ο γιός μου Γκότφριντ ήρθε στον κόσμο ενα τέταρτο μετά τις 7 το απόγευμα, στον αστερισμό του Υδροχόου."[1][2]

Ο πατέρας του πέθανε όταν αυτός ήταν εξίμιση χρονών, και από τότε και έπειτα ανέλαβε την ανατροφή του η μητέρα του.Τα διδάγματα της επηρέασαν τις φιλοσοφικές ανησυχίες του στη ζωή του αργότερα.[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

Ο πατέρας του Λάιμπνιτς ήταν καθηγητής Ηθικής Φιλοσοφίας στο Πανεπιστήμιο της Λειψίας,και το αγόρι αργότερα κληρονόμησε την προσωπική του βιβλιοθήκη.Του δόθηκε ελεύθερη πρόσβαση σε αυτή από την ηλικία των επτά.Ενώ τα σχολικά του μαθήματα βασίζονταν σε περιορισμένους κανόνες While Leibniz's schoolwork was largely confined to the study of a small canon of authorities, η βιβλιοθήκη του πατέρα του του επέτρεψε να ασχοληθεί με μία ευρύτερη ποικιλία προχωρημένων φιλοσοφικών και θεολογικών εργασιών που διαφορετικά δε θα μπορούσε να μελετήσει μέχρι τα πανεπιστημιακά του χρόνια.[3] Με την πρόσβαση στη βιβλιοθήκη του πατέρα του, γραμμένη κυρίως στα λατινικά, του πρόσφερε την άριστη γνώση της γλωσσας, από την ηλικία των 12. Επίσης συνέθεσε 300 εξάμετρα λατινικής ποίησης,μέσα σε ένα πρωινό, για μία σχολική εκδήλωση στην ηλικία των 13.[4]

Εγγράφηκε στο πανεπιστήμιο του πατέρα του στην ηλικία των 15 ,[5] και ολοκλήρωσε τις σπουδές του στη Φιλοσοφία το Δεκέμβριο του 1662. Επιμελήθηκε το Disputatio Metaphysica de Principio Individui,στο οποίο ασχολήθηκε με την Αρχη της Εξατομίκευσης, στις 9 Ιουνίου 1663. Ο Λάιμπνιτς απέκτησε το μεταπτυχιακό του στη Φιλοσοφία στις 7 Φεβρουαρίου του 1664. Δημοσίευσε τη διατριβή του Specimen Quaestionum Philosophicarum ex Jure collectarum, στην οποία υποστηρίζει την θεωρητική και παιδαγωγική σχέση μεταξύ της φιλοσοφίας και της νομικής το Δεκέμβριο του 1664 .Μετά από ένα χρόνο νομικών σπουδών απέκτησε το πτυχίο του στη Νομική στις 28 Σεπτεμβρίου 1665 .[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

1666–1674

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Πρώτη θέση του Λάιμπνιτς ήταν σαν μισθωτός γραμματέας σε μία αλχημική κοινωνία στη Νυρεμβεργη.[6] Ήξερε πολύ λίγα πάνω στο αντικείμενο εκείνη την εποχή αλλά παρουσίασε τον εαυτό του ως βαθιά καλλιεργημένος. Σύντομα γνώρισε τον Johann Christian von Boyneburg (1622–1672), τον πρώην επικεφαλή υπουργό , εκλεγμένο από το Μάιντς, Johann Philipp von Schönborn.[7] Von Boyneburg προσέλαβε τον Λάιμπνιτς ως βοηθό και σύντομα συμφιλιώθηκε με τον ελέκτορα και τον γνώρισε στον Λάιμπνιτς .Ο Λάιμπνιτς έπειτα αφιέρωσε μια έκθεση σχειά με το δίκιο του Ελέκτορα με σκοπό να αποκτήσει απασχόηση .Η στρατηγική λειτούργησε,ο Εκλέκτορας ζήτησε από τον Λάιμπνιτς να βοηθήσει με την αναδιατύπωση του νομικού κώδικα για το εκλογικό σώμα του .[8] Το 1669,ο Λάιμπνιτς ορίστηκε κριτής στο Εφετείο. Ωστόσο ο von Boyneburg πέθανε στα τέλη του 1672,ο Λάιμπνιτς παρέμεινε υπό την απασχόληση της χήρας του μέχρι που τον απέλυσε το 1674.[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

Ο Von Boyneburg έκανε πολλά για να προωθήσει τη φήμη του Λάιμπνιτς, και τα υπομνήματα και οι επιστολές του τελευταίου άρχισαν να προσελκύουν ευνοϊκές κριτικές. Σύντομα η υπηρεσία του Λάιμπνιτς ακολούθησε διπλωματικό ρόλο.Δημοσίευσε μία έκθεση με το ψευδώνυμο ένος φανταστικού Πολωνού ευγενή , υποστηρίζοντας ( ανεπιτυχώς ) για τη γερμανική υποψηφιότητα για το πολωνικό στέμμα. The main force in European geopolitics during Leibniz's adult life was the ambition of Louis XIV of France, backed by French military and economic might. Στο μεταξύ, ο Τριακονταετής πόλεμος άφησε πίσω του τη Γερμανική οικουμένη κατακερματισμένη και οικονομικά κατεστραμένη. Ο Λάιμπνιτς προτάθηκε να προστατέψει τη Γερμανόφωνη Ευρώπη. France would be invited to take Egypt as a stepping stone towards an eventual conquest of the Dutch East Indies. In return, France would agree to leave Germany and the Netherlands undisturbed. This plan obtained the Elector's cautious support. In 1672, the French government invited Leibniz to Paris for discussion,[9] but the plan was soon overtaken by the outbreak of the Franco-Dutch War and became irrelevant. Napoleon's failed invasion of Egypt in 1798 can be seen as an unwitting, late implementation of Leibniz's plan, after the Eastern hemisphere colonial supremacy in Europe had already passed from the Dutch to the British.[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

Έτσι ο Λάιμπνιτς έμεινε αρκετά χρόνια στο Παρίσι. Λίγο μετά την άφιξή του,συνάντησε τον Ολλανδό φυσικό και μαθηματικό Christiaan Huygens όπου συνειδητοποίησε πως η γνώση του πάνω στα μαθηματικά και τη φυσική ήταν ελλειπής. Με τον Huygens ως μέντορα, ξεκίνησε ένα πρόγραμμα αυτο-μελέτης που σύντομα τον ώθησε να συνεισφέρει σημαντικά και στα δύο αντικείμενα, the του διαφορικού και ολοκληρωτικού λογισμού. Συνάντησε τον Nicolas Malebranche και τον Antoine Arnauld, δύο κορυφαίους Γάλλους φιλόσοφους και μελέτησε γραπτά του Descartes και του Pascal, δημισιευμένα όπως και αδημοσίευτα. Έγινε φίλος με το Γερμανό μαθηματικό, Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus; αλληλογραφούσαν για το υπόλοιπο της ζωής τους. Το 1675 έγινε δεκτός από τη Γαλλική Ακαδημία Επιστημών ως επίτιμο μέλος, παρά το γεγονός ότι δεν παρακολουθούσε τα μαθήματα.[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

When it became clear that France would not implement its part of Leibniz's Egyptian plan, the Elector sent his nephew, escorted by Leibniz, on a related mission to the English government in London, early in 1673.[10] There Leibniz came into acquaintance of Henry Oldenburg and John Collins. He met with the Royal Society where he demonstrated a calculating machine that he had designed and had been building since 1670. The machine was able to execute all four basic operations (adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing), and the Society quickly made him an external member. The mission ended abruptly when news reached it of the Elector's death, whereupon Leibniz promptly returned to Paris and not, as had been planned, to Mainz.[11]

The sudden deaths of his two patrons in the same winter meant that Leibniz had to find a new basis for his career. In this regard, a 1669 invitation from the Duke of Brunswick to visit Hanover proved fateful. Leibniz declined the invitation, but began corresponding with the Duke in 1671. In 1673, the Duke offered him the post of Counsellor which Leibniz very reluctantly accepted two years later, only after it became clear that no employment in Paris, whose intellectual stimulation he relished, or with the Habsburg imperial court was forthcoming.[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

House of Hanover, 1676–1716

[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]{{Refimprove section|date=January 2014}} Leibniz managed to delay his arrival in Hanover until the end of 1676 after making one more short journey to London, where he was later accused by Newton of being shown some of Newton's unpublished work on the calculus.[12] This was alleged to be evidence supporting the accusation, made decades later, that he had stolen the calculus from Newton. On the journey from London to Hanover, Leibniz stopped in The Hague where he met Leeuwenhoek, the discoverer of microorganisms. He also spent several days in intense discussion with Spinoza, who had just completed his masterwork, the Ethics.[13]

In 1677, he was promoted, at his request, to Privy Counselor of Justice, a post he held for the rest of his life. Leibniz served three consecutive rulers of the House of Brunswick as historian, political adviser, and most consequentially, as librarian of the ducal library. He thenceforth employed his pen on all the various political, historical, and theological matters involving the House of Brunswick; the resulting documents form a valuable part of the historical record for the period.

Among the few people in north Germany to accept Leibniz were the Electress Sophia of Hanover (1630–1714), her daughter Sophia Charlotte of Hanover (1668–1705), the Queen of Prussia and his avowed disciple, and Caroline of Ansbach, the consort of her grandson, the future George II. To each of these women he was correspondent, adviser, and friend. In turn, they all approved of Leibniz more than did their spouses and the future king George I of Great Britain.[14]

The population of Hanover was only about 10,000, and its provinciality eventually grated on Leibniz. Nevertheless, to be a major courtier to the House of Brunswick was quite an honor, especially in light of the meteoric rise in the prestige of that House during Leibniz's association with it. In 1692, the Duke of Brunswick became a hereditary Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. The British Act of Settlement 1701 designated the Electress Sophia and her descent as the royal family of England, once both King William III and his sister-in-law and successor, Queen Anne, were dead. Leibniz played a role in the initiatives and negotiations leading up to that Act, but not always an effective one. For example, something he published anonymously in England, thinking to promote the Brunswick cause, was formally censured by the British Parliament.

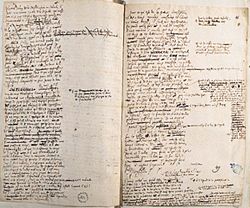

The Brunswicks tolerated the enormous effort Leibniz devoted to intellectual pursuits unrelated to his duties as a courtier, pursuits such as perfecting the calculus, writing about other mathematics, logic, physics, and philosophy, and keeping up a vast correspondence. He began working on the calculus in 1674; the earliest evidence of its use in his surviving notebooks is 1675. By 1677 he had a coherent system in hand, but did not publish it until 1684. Leibniz's most important mathematical papers were published between 1682 and 1692, usually in a journal which he and Otto Mencke founded in 1682, the Acta Eruditorum. That journal played a key role in advancing his mathematical and scientific reputation, which in turn enhanced his eminence in diplomacy, history, theology, and philosophy.

The Elector Ernest Augustus commissioned Leibniz to write a history of the House of Brunswick, going back to the time of Charlemagne or earlier, hoping that the resulting book would advance his dynastic ambitions. From 1687 to 1690, Leibniz traveled extensively in Germany, Austria, and Italy, seeking and finding archival materials bearing on this project. Decades went by but no history appeared; the next Elector became quite annoyed at Leibniz's apparent dilatoriness. Leibniz never finished the project, in part because of his huge output on many other fronts, but also because he insisted on writing a meticulously researched and erudite book based on archival sources, when his patrons would have been quite happy with a short popular book, one perhaps little more than a genealogy with commentary, to be completed in three years or less. They never knew that he had in fact carried out a fair part of his assigned task: when the material Leibniz had written and collected for his history of the House of Brunswick was finally published in the 19th century, it filled three volumes.

In 1708, John Keill, writing in the journal of the Royal Society and with Newton's presumed blessing, accused Leibniz of having plagiarized Newton's calculus.[15] Thus began the calculus priority dispute which darkened the remainder of Leibniz's life. A formal investigation by the Royal Society (in which Newton was an unacknowledged participant), undertaken in response to Leibniz's demand for a retraction, upheld Keill's charge. Historians of mathematics writing since 1900 or so have tended to acquit Leibniz, pointing to important differences between Leibniz's and Newton's versions of the calculus.

In 1711, while traveling in northern Europe, the Russian Tsar Peter the Great stopped in Hanover and met Leibniz, who then took some interest in Russian matters for the rest of his life. In 1712, Leibniz began a two-year residence in Vienna, where he was appointed Imperial Court Councillor to the Habsburgs. On the death of Queen Anne in 1714, Elector George Louis became King George I of Great Britain, under the terms of the 1701 Act of Settlement. Even though Leibniz had done much to bring about this happy event, it was not to be his hour of glory. Despite the intercession of the Princess of Wales, Caroline of Ansbach, George I forbade Leibniz to join him in London until he completed at least one volume of the history of the Brunswick family his father had commissioned nearly 30 years earlier. Moreover, for George I to include Leibniz in his London court would have been deemed insulting to Newton, who was seen as having won the calculus priority dispute and whose standing in British official circles could not have been higher. Finally, his dear friend and defender, the Dowager Electress Sophia, died in 1714.

- ↑ It is possible that the words "in Aquarius" refer to the Moon (the Sun in Cancer; Sagittarius rising (Ascendant)); see Astro-Databank chart of Gottfried Leibniz.

- ↑ The original has "1/4 uff 7 uhr" but there is no reason to assume that in the 17th century this meant a quarter to seven. The quote is given by Hartmut Hecht in Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (Teubner-Archiv zur Mathematik, Volume 2, 1992), in the first lines of chapter 2, Der junge Leibniz, p. 15; see H. Hecht, Der junge Leibniz; see also G. E. Guhrauer, G. W. Frhr. v. Leibnitz. B. 1. Breslau 1846, Anm. S. 4.

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 21

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 22

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 26

- ↑ Ariew R., G.W. Leibniz, life and works, p.21 in The Cambridge Companion to Leibniz, ed. by N. Jolley, Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 0521365880

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 43

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 44-45

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 58-61

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 69-70

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 73-74

- ↑ On the encounter between Newton and Leibniz and a review of the evidence, see Alfred Rupert Hall, Philosophers at War: The Quarrel Between Newton and Leibniz, (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 44–69.

- ↑ Mackie (1845), p.117-118

- ↑ For a study of Leibniz's correspondence with Sophia Charlotte, see MacDonald Ross, George, 1990, "Leibniz’s Exposition of His System to Queen Sophie Charlotte and Other Ladies." In Leibniz in Berlin, ed. H. Poser and A. Heinekamp, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1990, 61-69.

- ↑ Mackie (1845), 109