Χρήστης:Stelios2267/πρόχειρο/Αμφίβια

|

Αυτή η σελίδα είναι ένα «πρόχειρο χρήστη» του Stelios2267. Ένα «πρόχειρο χρήστη» είναι υποσελίδα της προσωπικής σελίδας του χρήστη στη Βικιπαίδεια. Εξυπηρετεί ως χώρος πειραματισμών και ανάπτυξης σελίδων και δεν είναι εγκυκλοπαιδικό λήμμα. Επεξεργαστείτε ή δημιουργήστε το δικό σας πρόχειρο εδώ ή κάνετε δοκιμές στο κοινόχρηστο Πρόχειρο Βικιπαίδειας. |

{{Άλλεςχρήσεις|Αμφίβιος (αποσαφήνιση)|Αμφίβια (αποσαφήνιση)}}

| Αμφίβια Χρονικό πλαίσιο απολιθωμάτων: Ύστερο Δεβόνιο–παρόν | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Δεξιόστροφα από πάνω δεξιά: Σεϋμούρια, Δερμόφις ο μεξικανός, Νωτόφθαλμος ο πρασινωπός και Λιτόρια η φυλλόχρους

| ||||||||

| Συστηματική ταξινόμηση | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Υφομοταξίες και Τάξεις | ||||||||

| ||||||||

Τα Αμφίβια είναι εξώθερμα, τετράποδα σπονδυλωτά που αποτελούν μία ομοταξία. Όλα τα σύγχρονα αμφίβια ανήκουν στα Λισσαμφίβια. Έχουν μεγάλη ποικιλία ενδιαιτημάτων και τα περισσότερα είδη απαντούν σε χερσαία, υπόγεια, δενδρικά ή γλυκά υδατικά οικοσυστήματα. Ο κύκλος ζωής τους είναι χαρκτηριστικός καθώς αρχίζουν την ζωή τους ως προνύμφες ζώντας στο νερό, αν και κάποια είδη έχουν αναπτύξει συμπεριφορικές προσαρμογές ώστε να παρακάμπτουν αυτό το στάδιο. Γενικά τα νεαρά άτομα υφίστανται μεταμόρφωση από την προνυμφική μορφή κατά την οποία έχουν βράγχια προς την ενήλικη μορφή οπότε αναπνέουν με πνεύμονες. Τα αμφίβια χρησιμοποιούν το δέρμα τους ως δευτερεύουσα αναπνευστική επιφάνεια και μάλιστα κάποιες μικρές χερσαίες σαλαμάνδρες και βάτραχοι δεν διαθέτουν καθόλου πνεύμονες και βασίζονται εξ ολοκλήρου στο δέρμα τους. Επιφανειακά μοιάζουν με τα ερπετά αλλά, μαζί με τα θηλαστικά και τα πτηνά, τα ερπετά είναι αμνιωτά και δεν χρειάζονται το νερό για να αναπαραχθούν. Με τις πολύπλοκες αναπαραγωγικές τους ανάγκες και το διαπερατό δέρμα τους, τα αμφίβια αποτελούν συχνά οικολογικούς δείκτες και τις τελευταίες δεκαετίες έχει παρατηρηθεί δραματική μείωση των πληθυσμών των αμφιβίων για πολλά είδη σε όλο τον κόσμο.

Τα πρώτα αμφίβια εξελίχθηκαν κατά την Δεβόνια περίοδο από τους σαρκοπτερύγιους ιχθύς που έφεραν πνεύμονες και οστέινα πτερύγια, χαρακτηριστικά αναγκαία για την προσαρμογή στη ξηρά. Διαφοροποιήθηκαν και κυριάρχησαν κατά την Λιθανθρακοφόρο και την Πέρμια περίοδο, αλλά αργότερα εκτοπίστηκαν από τα ερπετά και τα άλλα σπονδυλωτά. Προϊόντος του χρόνου, τα αμφίβια συρρικνώθηκαν και η ποικιλομορφία τους περιορίστηκε, ώστε απέμεινε μόνο η σύγχρονη υφομοταξία Λισσαμφίβια. Οι τρεις σύγχρονες τάξεις αμφιβίων είναι τα Άνουρα (οι βάτραχοι και οι φρύνοι), τα Ουροδελή/Κερκοφόρα (οι σαλαμάνδρες), και τα Γυμνοφίονα/Άποδα. Ο αριθμός των γνωστών ειδών αμφιβίων είναι κατά προσέγγιση 7.000, εκ των οποίων σχεδόν το 90% είναι βάτραχοι. Το μικρότερο αμφίβιο (και σπονδυλωτό) στον κόσμο είναι ένας βάτραχος από την Νέα Γουινέα (Paedophryne amauensis) με μήκος μόλις 7,7 χιλιοστόμετρα. Το μεγαλύτερο ζωντανό αμφίβιο είναι η 1,8 μέτρων Κινεζική γιγάντια σαλαμάνδρα (Andrias davidianus), αλλά και αυτή φαίνεται νάνος μπροστά στον εξαφανισμένο 9 μέτρων Πριονόσουχο από το μέσο Πέρμιο της Βραζιλίας. Η μελέτη των αμφιβίων ονομάζεται βατραχολογία, ενώ η μελέτη και των ερπετών και των αμφιβίων ονομάζεται ερπετολογία.

Ταξινόμηση[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Η λέξη "αμφίβιο" παράγεται από τον αρχαιοελληνικό όρο «ἀμφίβιος», που σημαίνει "αυτός που ζει με δύο τρόπους". Ο όρος αρχικά χρησιμοποιήθηκε ως γενικό επίθετο για ζώα που μπορούσαν να ζήσουν τόσο στην ξηρά όσο και στο νερό, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των φωκών και των ενυδρίδων.[2] Παραδοσιακά, η ομοταξία Αμφίβια περιλαμβάνει όλα τα τετράποδα σπονδυλωτά που δεν είναι αμνιωτά. Τα Αμφίβια υπό ευρείαν έννοιαν (sensu lato) διαιρούνταν σε τρεις υφομοταξίες, δύο εκ των οποίων είναι εξαφανισμένες:[3]

- Υφομοταξία Λαβυρινθοδόντια† (ανομοιογενής ομάδα του Παλαιοζωικού και του Μεσοζωικού)

- Υφομοταξία Λεποσπόνδυλα† (μικρή ομάδα του Παλαιοζωικού, κάποιες φορές περιλαμβάνεται στα Λαβυρινθοδόντια, τα οποία μπορεί στην πραγματικότητα να είναι πιο συγγενικά προς τα αμνιωτά σε σχέση με τα Λισσαμφίβια)

- Υφομοταξία Λισσαμφίβια (όλα τα σύγχρονα αμφίβια, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των βατράχων, των φρύνων, των σαλαμανδρών, των τριτώνων και των γυμνοφιόνων)

Ο πραγματικός αριθμός των ειδών σε κάθε ομάδα εξαρτάται από την ταξινόμηση που ακολουθείται. Τα δύο πιο συνηθισμένα συστήματα είναι η ταξινόμηση που υιοθετήθηκε από τον ιστότοπο AmphibiaWeb, (Πανεπιστήμιο της Καλιφόρνιας, Μπέρκλεϋ) και η ταξινόμηση του ερπετολόγου Ντάρρελ Φροστ και του Αμερικανικού Μουσείου Φυσικής Ιστορίας, διαθέσιμη στην ηλεκτρονική βάση δεδομένων αναφοράς "Amphibian Species of the World".[5] Οι προαναφερθέντες αριθμοί των ειδών ακολουθούν τον Φροστ και ο συνολικός αριθμός γνωστών αμφιβίων υπερβαίνει τις 7.000, εκ των οποίων σχεδόν το 90% είναι βάτραχοι.[6]

Με την φυλογενετική ταξινόμηση, το τάξον Λαβυρινθοδόντια έχει απορριφθεί ως πολυπαραφυλετική ομάδα χωρίς ταυτοποιητικά χαρακτηριστικά εκτός των κοινών προγονικών χαρακτηριστικών. Η ταξινόμηση ποικίλει ανάλογα με την προτιμώμενη φυλογένεση του συγγραφέα και το αν χρησιμοποιείται ταξινόμηση βάσει στελέχους ή βάσει κόμβου. Παραδοσιακά, τα αμφίβια ως ομοταξία ορίζονται ως τα τετράποδα με προνυμφικό στάδιο, ενώ η ομάδα που περιλαμβάνει τους κοινούς προγόνους όλων των ζωντανών αμφιβίων (βάραχοι, σαλαμάνδρες και γυμνοφίονα) και όλους τους απογόνους τους ονομάζεται Λισσαμφίβια. Η φυλογένεση των αμφιβίων του Παλαιοζωικού είναι αβέβαιη και τα Λισσαμφίβια μπορεί ενδεχομένως να εμπίπτουν σε εξαφανισμένες ομάδες, όπως τα Τεμνοσπόνδυλα (που παραδοσιακά τοποθετούνται στην υφομοταξία Λαβυρινθοδόντια) ή τα Λεποσπόνδυλα και σύμφωνα με κάποιες αναλύσεις ακόμη και στα αμνιωτά. Αυτό σημαίνει ότι υποστηρικτές της φυλογενετικής ονοματολογίας μετακίνησαν ένα μεγάλο αριθμό βασικών ομάδων τετραπόδων τύπου αμφιβίου της Δεβονίου και Λιθανθρακοφόρου περιόδου που παλαιότερα τοποθετούνταν στα Αμφίβια στην ταξινομία του Λινναίου, και και τα συμπεριέλαβαν αλλού σύμφωνα με την κλαδιστική ταξονομία.[1] Αν ο κοινός πρόγονος των αμφιβίων και των αμνιωτών περιλαμβάνεται στα Αμφίβια, γίνεται παραφυλετική ομάδα.[7]

Όλα τα σύγχρονα αμφίβια περιλαμβάνονται στην υφομοταξία των Λισσαμφιβίων, η οποία συνήθως θεωρείται κλάδος, μία ομάδα ειδών που έχουν εξελιχθεί από ένα κοινό πρόγονο. Οι τρεις σύγχρονες τάξεις είναι τα Άνουρα (βάτρχοι και φρύνοι), τα Ουρόδηλα (ή Κερκοφόρα, οι σαλαμάνδρες), και τα Γυμνοφίονα (ή Άποδα, τα καικίλια).[8] Υπάρχει η άποψη ότι οι σαλαμάνδρες προήλθαν ξεχωριστά από Τεμνοσπονδυλόμορφους προγόνους και ακόμη ότι τα καικιλίδια αποτελούν την αδελφή ομάδα των ανεπτυγμένων ερπετόμορφων αμφιβίβων, και ως εκ τούτου των αμνιωτών.[9] Μολονότι υπάρχουν γνωστά απολιθώματα αρκετών παλαιότερων πρωτοβατράχων με πρωτόγονα χαρακτηριστικά, ο παλαιότερος "γνήσιος βάτραχος" είναι ο Prosalirus bitis, από τον Σχηματσιμό Καγιέντα του Πρώιμου Ιουρασικού στην Αριζόνα. Παρουσιάζει ανατομικά πολύ μεγάλη ομοιότητα με τους σύγχρονους βατράχους.[10] Το παλιότερο γνωστό καικίλιο είναι άλλο ένα είδος του Πρώιμου Ιουρασικού, η Eocaecilia micropodia και είναι και αυτό από την Αριζόνα.[11] Η παλαιότερη σαλαμάνδρα είναι το Beiyanerpeton jianpingensis του Ύστερου Ιουρασικού της βορειοανατολικής Κίνας.[12]

Υπάρχει διαφωνία για το αν τα Πηδητικά αποτελούν υπερτάξη που περιλαμβάνει την τάξη Άνουρα, ή αν τα Άνουρα είναι υπόταξη της τάξεως των Πηδητικών. Τα Λισσαμφίβια διαιρούνται παραδοσιακά σε τρεις τάξεις, αλλά μία εξαφανσιμένη οικογένεια σαλαμανδρόμορφων, οι Αλβανερπετοντίδες, θεωρούνται πλέον μέρος των Λισσαμφιβίων μαζί με την υπέρταξη Πηδητικά. Επιπλέον, τα Πηδητικά περιλαμβάνουν όλες τις τρεις σύγχρονες τάξεις συν τον Τριαδικό πρωτοβάτραχο, Τριαδοβάτραχο.[13]

Εξελικτική ιστορία[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Οι πρώτες κύριες ομάδες αμφιβίων αναπτύχθηκαν κατά την Δεβόνια περίοδο, γύρω στα 370 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν, από τους Σαρκοπτερυγίους οι οποίοι ήταν παρόμοιοι με τον σύγχρονο κοιλάκανθο και με τους δίπνοους.[14] Αυτοί οι αρχαίοι σαρκοπτερύγιοι ιχθύες είχαν εξελίξει πολυαρθρωτά, όμοια με άκρα, πτερύγια που έφεραν δάκτυλα τα οποία τους επέτρεπαν να έρπουν κατά μήκος του θαλάσσιου πυθμένα. Κάποιοι ιχθύες είχαν αναπτύξει πρωτόγονους πνέυμονες για να τους βοηθούν να αναπνέουν αέρα όταν τα στάσιμα νερά των ελών του Δεβονίου είχαν χαμηλή περιεκτικότητα οξυγόνου. Μπορούσαν επίσης να χρησιμοποιούν τα δυνατά πετερύγιά τους για να σηκώνονται έξω από το νερό και να βγαίνουν στην ξηρά αν το απαιτούσαν οι περιστάσεις. Τελικά, τα σωματικά τους πτερύγια θα εξελίσσονταν σε άκρα και αυτοί θα γίνονταν οι πρόγονοι όλων των τετραπόδων, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των σύγχρονων αμφιβίων, των ερπετών, των πτηνών και των θηλαστικών. Ανεξάρτητα από την ικανότητά τους να έρπουν στην γη, πολλά από αυτά τα προϊστορικά τετραποδόμορφα ψάρια συνέχιζαν να περνούν το μεγαλύτερο μέρος του χρόνου τους στο νερό. Είχαν αρχίσει να αναπτύσσουν πνεύμονες, αλλά συνέχιζανα να αναπνεόυν κυρίως με βράγχια.[15]

Υπάρχουν πολλά παραδείγματα ειδών που παρουσιάζουν μεταβατικά χαρακτηριστικά. Η Ιχθυόστεγα ήταν ένα από τα πρώτα πρωτόγονα αμφίβια, με ρώθωνες και αποτελεσματικότερους πνεύμονες. Είχε τέσσερα εύρωστα άκρα, λαιμό, ουρά με πτερύγια και κρανίο παρόμοιο με αυτό του σαρκοπτερυγίου Ευσθενοπτέρου.[14] Τα αμφίβια ανέπτυξαν προσαρμογές που τους επέτρεψαν να παραμένουν έξω από το νερό για μεγάλα χρονικά διαστήματα. Οι πνεύμονές τους βελτιώθηκαν και οι σκελετοί τους έγιναν βαρύτεροι και δυνατότεροι, ικανότεροι να υποστηρίξουν το βάρος του σώματός τους στην ξηρά. Ανέπτυξαν "χέρια" και "πόδια" με πέντε ή περισσότερα δάκτυλα·[16] Το δέρμα έγινε ικανότερο να συγκρατεί τα υγρά του σώματος και να ανθίσταται στην αφυδάτωση.[15] Το υογναθικό οστό των ιχθύων στην υοειδή περιοχή πίσω από τα βράγχια συρρικνώνεται και γίνεται ο αναβολέας του αυτιού των αμφιβίων, προσαρμογή αναγκαία για την ακοή στην ξηρά.[17] Μία ομοιότητα μεταξύ των αμφιβίων και των Τελεόστεων ιχθύων είναι η πολύπτυχη δομή των δοντιών και το ζέυγος υπερινιακών οστών στο οπίσθιο μέρος της κεφαλής· κανένα από αυτά τα χαρακτηριστικά δεν απαντάται αλλού στο ζωικό βασίλειο.[18]

Στο τέλος της Δεβονίου περιόδου (360 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν), οι θάλασσες, οι ποταμοί και οι λίμνες έσφυζαν από ζωή ενώ η ξηρά ήταν το βασίλειο των πρώιμων φυτών με πλήρη απουσία σπονδυλωτών,[18] αν και κάποια, όπως η Ιχθυόστεγα, μπορεί κάποιες φορές να έβγαιναν έξω από το νερό. Πιστέυεται ότι έδιναν ώθηση με τα μπροστινά άκρα, σερνώμενα με παρόμοιο τρόπο με αυτόν των θαλάσσιων ελεφάντων.[16] Κατά την πρώιμη Λιθανθρακοφόρο (360 με 345 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν), το κλίμα έγινε υγρό και θερμό. Αναπτύχθηκαν εκτεταμένα έλη με βρύα, φτέρες, Εκουιζέτα και Καλαμίτες. Εξελίχθηκαν πολλά αρθρόποδα που ανέπνεαν αέρα και εισέβαλαν στην ξηρά ώστε παρείχαν τροφή για τα σαρκοφάγα αμφίβια που άρχισαν να προσαρμόζονται στο χερσαίο περιβάλλον. Δεν υπήρχαν άλλα τετράποδα στην ξηρά και τα Αμφίβια βρίσκονταν στην κορυφή της τροφικής αλυσίδας, κατ'εχοντας την οικολογική θέση που σήμερα κατέχει ο κροκόδειλος. Μολονότι εξοπλισμένα με άκρα και την ικανότητα να αναπνεόυν στον αέρα, τα περισσότερα είχαν ακόμα μακρύ κωνοειδές σώμα και δυνατή ουρά.[18] Ήταν οι κορυφαίοι χερσαίοι θηρευτές, φτάνοντας κάποιες φορές αρκετά μέτρα στο μήκος, κυνηγώντας μεγάλα έντομα της περιόδου και πολλά είδη ψαριών στο νερό. Βέβαια, χρειαζόταν να επιστρέφουν στο νερό για να γεννήσουν τα ακέλυφα αυγά τους και τα περισσότερα σύγχρονα αμφίβια έχουν ακόμα πλήρες υδρόβιο προνυμφικό στάδιο με βράγχια όπως οι ιχθύες πρόγονοί τους. Ήταν η ανάπτυξη των αμνιωτικών αυγών, η οποία προφυλάσσει το αναπτυσσόμενο έμβρυο από την αφυδάτωση, που έδωσε την δυνατότητα στα ερπετά να αναπαράγονται στην ξηρά και που οδήγησε στην κυριαρχία τους κατά την περίοδο που ακολούθησε.[14]

Μετά την κατάρρευση των βροχερών δασών της Λιθανθρακοφόρου η κυριαρχία των αμφιβίων έδωσε θεση στην κυριαρχία των ερπετών,[19] και τα αμφίβια μειώθηκαν περαιτέρω από την μαζική εξαφάνιση Περμίου-Τραδικού.[20] Κατά την διάρκεια της Τριαδικής περιόδου (250 με 200 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν), τα ερπετά συνέχιζαν να υποσκελίζουν τα αμφίβια, οδηγώντας σε μείωση και του μεγέθους των αμφιβίων και της σημασίας τους στην βιόσφαιρα. Σύμφωνα με τις καταγραφές των απολιθωμάτων, τα Λισσαμφίβια, τα οποία περιλαμβάνουν όλα τα σύγχρονα αμφίβια και τα οποία αποτελούν τον μόνο επιζήσαντα κλάδο, μπορεί να αποκόπηκαν από τις εξαφανισμένες ομάδες των Τεμνοσπονδύλων και των Λεποσπονδύλων σε κάποια περίοδο μεταξύ του Ύστερου Λιθανθρακοφόρου και του Πρώιμου Τριαδικού. Η σχετική έλλειψη απολιθωμάτων εμποδίζει την ακριβή χρονολόγηση,[15] αλλά η πιο σύγχρονη μοριακή μελέτη, βασιζόμενη σε MLST, προτείνει ως προέλευση το Ύστερο Λιθανθρακοφόρο/Πρώιμο Πέρμιο για τα σωζόμενα αμφίβια.[21]

Η προέλευση και οι εξελικτικές σχέσεις μεταξύ των κυρίων τριών ομάδων αμφιβίων αποτελεί αντικείμενο συζήτησης. Μία μοριακή φυλογένεση του 2005, βασισμένη σε ανάλυση rDNA, προτείνει ότι οι σαλαμάνδρες και τα καικιλίδια συνδέονται στενότερα μεταξύ τους από ότι με τους βατράχους. Επίσης εμφανίζεται ότι η απόκλιση των τριών ομάδων πραγματοποιήθηκε στο Παλαιοζωικό ή στο πρώιμο Μεσοζωικό (περίπου 250 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν), πριν από την διάσπαση της υπερηπείρου Παγγαίας και σύντομα μετά την απόκλιση τους από τους σαρκοπτερυγίους ιχθύς. Η βραχύτητα της περιόδου και η ταχύτητα με την οποία πραγματοποιήθηκε η ακτινωτή διαφοροποίηση, θα βοηθούσε στην εξήγηση της σχετικής σπάνεως απολιθωμάτων πρωτόγονων αμφιβίων.[22] Υπάρχουν μεγάλα κενά στο αρχείο απολιθωμάτων, αλλά η ανακάλυψη ενός πρωτοβατράχου από το Πρώιμο Πέρμιο στο Τέξας το 2008 έδειξε τον χαμένο κρίκο με πολλά από τα χαρακτηριστικά των σύγχρονων βατράχων. Μοριακή ανάλυση προτείνει ότι η απόκλιση των βατράχων από τις σαλαμάνδρες έλαβε χώρα αρκετά νωρίτερα από ότι δείχνουν τα παλαιοντολογικά στοιχεία.[9]

Καθώς εξελίχθηκαν από πνευμονοφόρα ψάρια, τα αμφίβια έπρεπε να κάνουν ορισμένες προσαρμογές για να ζήσουν στην ξηρά συμπεριλαμβανομένης της ανάγκης αναπτύξεως νέων μέσων κινήσεως. Στο νερό, οι πλάγιες ωθήσεις της ουράς τους τα ωθούσαν προς τα εμπρός, αλλά στην ξηρά, απαιτούνταν αρκετά διαφορετικοί μηχανισμοί. Οι σπονδυλική τους στήλη, τα άκρα, οι ζώνες των άκρων και οι μύες χρειαζόταν να είναι αρκετά δυνατοί ωστε να τα σηκώσουν από το έδαφος για κίνηση και σίτηση. Τα χερσαία ενήλικα άτομα απέβαλαν το σύστημα της πλευρικής γραμμής και προσάρμοσαν το σύστημα αισθητηρίων τους ώστε να λαμβάνει ερεθίσματα δια μέσου του αέρα. Χρειάστηκε να αναπτύξουν νέες μεθόδους για να ρυθμίζουν τη θερμότητα του σώματός τους ώστε να αντιμετωπίζουν τις διακυμάνσεις της θερμοκρασίας του περιβάλλοντος. Ανέπτυξαν συμπεριφορές κατάλληλες για την αναπαραγωγή σε χερσαίο περιβάλλον. Τό δέρμα τους εκτέθηκε στις βλαβερές υπεριώδεις ακτίνες που προηγουμένως απορροφόνταν από το νερό. Το δέρμα άλλαξε για να προστατεύει αποτελεσματικότερα και να εμποδίζει την υπερβολική απώλεια νερού.[23]

Χαρακτηριστικά[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Η υπερομοταξία Τετράποδα διαιρείται σε τέσσερεις ομοταξίες σπονδυλοζώων με τέσσερα άκρα.[24] Τα ερπετά, τα πτηνά και τα θηλαστικά είναι αμνιωτά, τα αυγά των οποίων είτε γεννώνται είτε μεταφέρονται από το θηλυκό και περιβάλλονται από αρκετές μεμβράνες, μερικές από τις οποίες είναι αδιαπέραστες.[25] Ελλειπούσης αυτής της μεμβράνης, τα αμφίβια χρειάζονται νερό για να μπορούν να αναπαραχθούν, αν και κάποια είδη έχουν αναπτύξει ποικίλες στρατηγικές για να προστατεύουν ή να παρακάμπτουν το ευάλωτο υδρόβιο προνυμφικό στάδιο.[23] Δεν απαντούν στην θάλασσα με εξαίρεση ενός ή δύο βατράχων που ζουν σε υφάλμυρα νερά σε έλη μαγκροβίων.[26] Στην ξηρά, τα αμφίβια περιορίζονται σε υγρά ενδιαιτήματα εξαιτίας της ανάγκης διατήρησης της υγρότητας του δέρματος.[23]

Το μικρότερο αμφίβιο (και σπονδυλωτό) στον κόσμο είναι ένας μικροϋλίδας βάτραχος από την Νέα Γουινέα (Paedophryne amauensis) που πρωτοανακαλύφθηκε το 2012. Έχει κατα μέσο όρο μήκος 7,7 χιλιοστομέτρων και ανήκει σε ένα γένος που περιέχει τέσσερα από τα δέκα μικρότερα είδη βατράχων.[27] Το μεγαλύτερο ζωντανό αμφίβιο είναι η 1,8 μέτρων κινεζική γιγάντια σαλαμάνδρα (Andrias davidianus)[28] αλλά και αυτή είναι κατά πολύ μικρότερη από το μεγαλύτερο αμφίβιο που υπήρξε ποτέ —τον εξαφανισμένο 9μετρο Πριονόσουχο, ένα κροκοδειλόμορφο τεμνοσπόνδυλο που χρονολογείται στα 270 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν, από το μέσο Πέρμιο της Βραζιλίας.[29] Ο μεγαλύτερος βάτραχος είναι ο αφρικανικός βάτραχος Γολιάθ (Conraua goliath), ο οποίος μπορεί να φτάσει τα 32 εκατοστόμετρα σε μήκος και τα 3 χιλιόγραμμα σε βάρος[28]

Τα αμφίβια είναι εξώθερμα (ψυχρόαιμα) σπονδυλωτά που δεν διατηρούν την θερμοκρασία του σώματός τους μέσω εσωτερικών φυσιολογικών διαδικασιών. Ο μεταβολικός ρυθμός τους είναι χαμηλός και ως αποτέλεσμα, οι τροφικές και ενεργειακές τους ανάγκες είναι περιορισμένες. Στο ενήλικο στάδιο, φέρουν δακρυϊκούς πόρους και κινητά βλάφαρα και τα περισσότερα είδη διαθέτουν αφτιά που ανιχνεύουν δονήσεις του αέρα και του εδάφους. Έχουν μυώδη γλώσσα, οι οποία σε πολλά είδη είναι εκτατή. Τα σύγχρονα αμφίβια έχουν πλήρως οστεοποιημένους σπονδύλους με αρθρικές αποφύσεις. Οι πλευρές τους είναι σηνήθως κοντές και μπορεί να είναι συγχωνευμένες με τους σπονδύλους. Το κρανίο τους είναι ως επι το πλείστον πλατύ και βραχύ και είναι συχνά ατελώς οστεοποιημένο. Το δέρμα τους περιέχει λίγη κερατίνη και καθόλου λέπια, με εξαίρση κάποια λίγα λέπια σε ορισμένα καικίλια. Το δέρμα περιέχει πολλούς βλεννογόνους αδένες και σε κάποια είδη, δηλητηριώδεις αδένες. Η καρδιά των αμφιβίων είναι τρίχωρη, δηλαδή έχει τρεις χώρους, δύο κόλπους και μία κοιλία. Έχουν μία ουροδόχο κύστη και τα αζωτούχα απόβλητα απεκκρίνονται κυρίως ως ουρία. Τα περισσότερα είδη μαφιβίων γεννούν τα αυγά τους στο νερό και γεννιούνται ως υδρόβιες προνύμφες που υφίστανται μεταμόρφωση για να γίνουν χερσαία ενήλικα άτομα. Τα αμφίβια αναπνέουν μέσω μίας διαδικασίας αντλήσεως στην οποία αέρας πρώτα εισέρχεται στην στοματοφαρυγγική περιοχή από τους ρώθωνες. Αυτοί στην συνέχεια κλείνουν και ο αέρας ωθείται στους πνεύμονες με σύσπαση του λαιμού.[30] Αυτή η διαδικασία συμπληρώνεται από ανταλλαγή αερίων μέω του δέρματος.[23]

Άνουρα[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Η τάξη Άνουρα περιλαμβάνει τους βατράχους και τους φρύνους. Συνήθως έχουν μακριά πισινά πόδια που αναδιπλώνονται από κάτω τους, κοντύτερα μπροστινά πόδια, δάχτυλα ενωμένα με μεμβράνη χωρίς γαμψώνυχες, δεν έχουν ουρά, διαθέτουν μεγάλα μάτια και αδενώδες υγρό δέρμα.[8] Τα μέλη αυτής της τάξης που έχουν λείο δέρμα αναφέρονται συνήθως ως βάτραχοι, ενώ αυτά μετραχύ γεμάτο φύματα είναι γνωστά ως φρύνοι. Η διαφορά δεν είναι επίσημη ταξονομικώς και και υπάρχουν πολυάριθμες εξαιρέσεις σε αυτόν τον κανόνα. Τα μέλη της οικογένειας των Φρυνιδών είναι γνωστά ως "γνήσιοι φρύνοι".[31] Το μέγεθος των βατράχων κυμαίνεται από από 30 εκατοστόμετρα (βάτραχος Γολιάθ (Conraua goliath) της Δυτικής Αφρικής)[32] σε 7,7 χιλιοστόμετρα (Paedophryne amauensis, περιγράφηκε πρώτη φορά στην Παπούα Νέα Γουινέα το 2012, και είναι επίσης το μικρότερο γνωστό σπονδυλωτό).[33] Αν και τα περισσότερα είδη συνδέονται με νερό και υγρά ενδιαιτήματα, κάποια ειδικεύονται στην ζωή στα δέντρα ή στην έρημο. Απαντούν σε όλον τον κόσμο πλην των πολικών περιοχών.[34]

Τα άνουρα διαιρούνται σε τρεις υποτάξεις που είναι ευρέως αποδεκτές από την επιστημονική κοινότητα, αλλά οι σχέσεις μεταξύ ορισμένων οικογενειών παραμένουν ασαφείς. Μελλοντικές μοριακές μελέτες θα παράσχουν περισσότερες πληροφορίες σχετικά με τις εξελικτικές σχέσεις.[35] Η υπόταξη Αρχαιοβατράχια περιλαμβάνει τέσσερεις οικογένειες πρωτόγονων βατράχων. Αυτές είναι οι Ασκαφίδες, οι Βομβινατορίδες, οι Δισκογλωσσίδες και οι Λειοπελματίδες που έχουν έχουν λίγα προερχόμενα χαρακτηριστικά και είναι ενδεχομένως παραφυλετική εν σχέσει με άλλες γραμμές καταγωγείς βατράχων.[36] Οι έξι οικογένειες στην εξελικτικά πιο ανεπτυγμένη υπόταξη Μεσοβατράχια είναι οι σκαπτικοί Μεγοφρυΐδες, οι Πηλοβατίδες, οι Πηλοδυτίδες, οι Σκαφιοποδίδες και οι Ρινοφρυνίδες και οι αποκλειστικά υδρόβιοι Πιπίδες. Έχουν ορισμένα χαρακτηριστικά τα οποία είναι ενδιάμεσα μεταξύ των δύο άλλων υποτάξεων.[36] Τα Νεοβατράχια είναι κατά πολύ η μεγαλύτερη υπόταξη και περιλαμβάνει τις υπόλποιπες οικογένειες των σύγχρονων βατράχων, συμπεριλαμβάνοντας μερικά από τα πλέον κοινά είδη. Το 96% των πάνω από 5.000 σωζόμενων ειδών βατράχων είναι Νεοβατράχια.[37]

Ουροδελή[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

(Andrias japonicus), μία πρωτόγονη σαλαμάνδρα

Η τάξη Ουροδελή αποτελείται από τις σαλαμάνδρες—επιμήκη, χαμηλά ζώα που στην μορφή μοιάζουν κυρίως με σαύρες. Αυτό είναι συμπλησιομορφικό χαρακτηριστικό και τα ουροδελή δεν δεν έχουν μεγαλύτερη συγγενική σχέση με τις σαύρες από όση με τα θηλαστικά.[38] Οι σαλαμάνδρες δν φέρουν γαμψώνυχες, έχουν δέρμα χωρίς λέπια, είτε λείο είτε καλυμμένο με φύματα, και ουρά που είναι συνήθως πεπλατυσμένη και συχνά σαν πτερύγιο. Κυμαίνονται σε μέγεθος από την κινεζική γιγάντια σαλαμάνδρα (Andrias davidianus), η οποία έχει αναφερθεί να φτάνει σε μήκος τα 1,8 μέτρα,[39] στο μικροσκοπικό είδος Thorius pennatulus από το Μεξικό το οποίο σπανίως υπερβαίνει τα 20 χιλιοστόμετρα σε μήκος.[40] Οι σαλαμάνδρες έχουν κυρίως Λαυρασιατική κατανομή, απαντώντας στο μεγαλύτερο μέρος της Ολαρκτικής περιοχής του βορείου ημισφαιρίου. Η οικογένεια των Πληθοδοντιδών απαντά επίσης στην Κεντρική Αμερική και την Νότια Αμερική βορείως της λεκάνης του Αμαζονίου·[34] Η Νότια Αμερική δέχτηκε προφανώς την εισβολή τους από την Κεντρική Αμερική περίπου κατά την αρχή του Μειοκαίνου, 23 εκατομμύρια χρόνια πριν.[41] Μέλη αρκετών οικογενειών Ουροδελών έχουν γίνει νεοτενικά και είτε δεν ολοκληρώνουν τη μεταμόρφωσή τους ή διατηρούν ορισμένα προνυμφικά χαρακτηριστικά ως ενήλικα.[42] Οι περισσότερες σαλαμάνδρες έχουν μήκος μικρότερο των 15 εκατοστών. Μπορεί να είναι χερσόβιες η υδρόβιες και πολλές περνούν ένα μέρος του χρόνου σε κάθε ένα ενδιαίτημα. Στην ξηρά, περνούν την μέρα τους κρυμμένες κάτω από πέτρες ή κορμούς ή μέσα σε πυκνή βλάστηση, και και βγαίνουν όταν νυχτώσει προς αναζητηση σκωλήκων, εντόμων και άλλων ασπονδύλων.[34]

(Triturus dobrogicus), μία ανεπτυγμένη σαλαμάνδρα

Η υπόταξη Κρυπτοβραγχοειδή περιλαμβάνει τις πρωτόγονες σαλαμάνδρες. Έχει βρεθεί ένας αριθμός απολιθωμάτων Κρυπτοβαγχοειδών, αλλά υπάρχουν μόνο τρία ζωντανά είδη, η κινεζική γιγάντια σαλαμάνδρα (Andrias davidianus), η ιαπωνική γιγάντια σαλαμάνδρα (Andrias japonicus) και ο Κρυπτόβραγχος (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) από την Βόρεια Αμερική. Αυτά τα μεγάλα αμφίβια διατηρούν αρκετά προνυμφικά χαρακτηριστικά ως ενήλικα· εμφανίζονται βραγχιακές σχισμές και οι οφθαλμοί δν έχουν βλέφαρα. Ένα μοναδικό χαρακτηριστικό είναι η ικανότητά τους να τρέφονται με αναρρόφηση, πιέζοντας είτε την αριστερή πλευρά της κάτω γνάθου τους είτε την δεξιά.[43]Τα αρσενικά σκάβουν φωλιές, πείθουν τα θηλυκά να γεννήσουν τα αυγά τους μέσα και τα φρουρούν. Μαζί με την πνευμονική αναπνοή, αναπνέουν μέσω των εκπτυχώσεων στο δέρμα τους, το οποίο έχει πολλά τριχοειδή αγγεία κοντά στην επιφάνειά του.[44]

Η υπόταξη Σαλαμανδροειδή περιλαμβάνει τις ανεπτυγμένες σαλαμάνδρες. Διαφέρουν από τα Κρυπτοβραγχοειδή στο ότι έχουν προαρθρωτά οστά στην κάτω γνάθο και από την εσωτερική γονιμοποίηση. Στα σαλαμανδροειδή, το αρσενικό εναποθέτει έναν σωρό σπέρματος, τον σπερματοφόρο, και το θηλυκό το παίρνει και το εισάγει στην αμάρα του όπου και αποθηκεύεται το σπέρμα έως ότου γεννηθούν τα αβγά.[45] Η μεγαλύτερη οικογένεια αυτής της ομάδας είναι οι Πληθοδοντίδες, σαλαμάνδρες χωρίς πνεύμονες, και περιλαμβάνει το 60% όλων των ειδών σαλαμανδρών. Η οικογένεια των Σαλαμανδριδών περιλαμβάνει τις γνήσιες σαλαμάνδρες και η ονομασία "τρίτωνας" δίνεται σε μέλη της υποοικογένειάς της, των Πλευροδελινών.[8]

Η τρίτη υπόταξη, τα Σειρηνοειδή, περιλαμβάνει τα τέσσερα είδη των σειρήνων, με μία μόνο οικογένεια, αυτή των Σειρηνιδών. Τα μέλη της υποτάξεως αυτής είναι υδρόβιες σαλαμάνδρες που μοιάζουν με χέλια με πολύ μειωμένα μπροστινά άκρα και καθόλου οπίσθια άκρα.[46] Η γονιμοποίηση πιθανώς είναι εξωτερική καθώς οι σειρηνίδες στερούνται των αδένων της αμάρας που χρησιμοποιούνται από τους αρσενικούς σαλαμανδρίδες για την παραγωγή σπερματοφόρων και τα οι θηλυκοί δεν διαθέτουν σπερματοθήκες για την αποθήκευση του σπέρματος. Παρά ταύτα, τα αυγά γεννιούνται μεμονωμένα, συμπεριφορά που δεν ευνοεί την εξωτερική γονιμοποίηση.[45]

Γυμνοφίονα ή Άποδα[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Η τάξη Άποδα ή Γυμνοφίονα περιλαμβάνει τους καικιλίες ή καικίλια (από το λατινικό caecus που σημαίνει τυφλός). Είναι επιμήκη, κυλινδρικά, άποδα ζώα οφιοειδή ή σκωληκόμορφα. Το μήκος των ενηλίκων ποικίλλει, και κυμαίνεται από 8 έως 75 εκατοστόμετρα με εξαίρεση το είδος Caecilia thompsoni, που μπορεί να φτάσει σε μήκος έως και τα 150 εκατοστόμετρα. Το δέρμα των απόδων παρουσιάζει μεγάλο αριθμό εγκάρσιων πτυχών και σε κάποια είδη περιλαμβάνει μικροσκοπικά σφηνωμένα δερματικά λέπια. Έχουν υποτυπώδη μάτια καλυμμένα από δέρμα, τα οποία πιθανώς περιορίζονται στο να διακρίνουν τις διαφορές της έντασης του φωτός. Επίσης έχουν ένα ζεύγος κοντών πλοκάμων κοντά στο μάτι που μπορουν να εκτινάζονται προς τα εμπρός και οι οποίοι έχουν απτικές και οσφρητικές λειτουργίες. Τα περισσότερα άποδα ζουν υπογείως σε λαγούμια στο υγρό χώμα, σε σάπια ξύλα και κάτω από φυτικά υπολείματα, αν και ορισμένα είναι υδρόβια.[47] Τα περισσότερα είδη γεννούν τα αυγά τους κάτα από το έδαφος και όταν οι προνύμφες εκκολάπτονται, κατευθύνονται αμέσως σε παρακείμενα υδάτινα σώματα. Άλλα, επωάζουν τα αυγά τους και οι προνύμφες υφίστανται μεταμόρφωση προτού αυτά εκκολαφθούν. Λίγα είδη γεννούν ζωντανά νεαρά, τρέφοντάς τα με αδενικές εκκρίσεις όσο βρίσκονται στον ωαγωγό.[48] Τα Άποδα απαντούν κυρίως σε τροπικές περιοχές της Αφρικής, της Ασίας και της Κεντρικής και Νότιας Αμερικής.[49]

Ανατομία και φυσιολογία[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Δέρμα[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Η καλυπτήρια δομή περιλαμβάνει κάποια τυπικά χαρακτηριστικά κοινά στα χερσαία σπονδυλόζωα, όπως η εμφάνιση κερατινοποιημένων σε μεγάλο βαθμό εξωτερικών στρωμάτων, ανανεούμενων περιοδικά μέσω μίας διαδικασίας έκδυσης που ελέγχεται από την υπόφυση και τον θυρεοειδή αδένα. Συνηθισμένες είναι τοπικές παχύνσεις (συχνά καλούνται τυλώματα ή φύματα), όπως αυτές που στους φρύνους. Η επιδερμική στιβάδα αποβάλλεται περιοδικά περισσότερο ή λιγότερο ως ένα μόνο κομμάτι, εν αντιθέσει με τα θηλαστικά και τα πτηνά των οποίων απορρίπτεται σε μικρά τεμάχια. Τα αμφίβια συχνά τρώνε το δέρμα που αποβάλλουν.[34] Τα Άποδα είναι μοναδικά μεταξύ των αμφιβίων καθώς διαθέτουν δερμικά λέπια βαθιά μέσα στο χόριο μεταξύ αυλακώσεων στο δέρμα. Η ομοιότητα αυτών με τα λέπια των οστεϊχθύων είναι σε μεγάλο βαθμό επιφανειακή. Τα Λεπιδωτά (σάυρες, φίδια) και κάποι βάτραχοι εμφανίζουν κάπως παρόμοια οστεοδέρματα που σχηματίζουν οστικές αποθέσεις στο χόριο, αλλά πρόκειται για συγκλίνουσα εξέλιξη με ανεξάρτητη ανάπτυξη παρεμφερών δομών σε διαφορετικές γεννεαλογικές γραμμές των σπονδυλωτών.[50]

Το δέρμα των αμφιβίων είναι υδατοπερατό. Η ανταλλαγή αερίων μπορεί να πραγματοποιηθεί και μέσω του δέρματος (δερματική αναπνοή) πρἀγμα που επιτρέπει στα ενήλικα αμφίβια να αναπνέουν χωρίς να ανεβαίνουν στην επιφάνεια του νερού να διαχειμάζουν στον βυθό νερόλακκων.[34] Για να μπορεί να διατηρείται το δέρμα λεπτό και μαλακό, τα αμφίβια έχουν αναπτύξει βλεννογόνους αδένες, κυρίως στην κεφαλή, στην ράχη και στην ουρά. Οι εκκρίσεις αυτών βοηθούν στο να διατηρείται το δέρμα πάντα υγρό. Επιπλέον, τα περισσότερα είδη αμφιβίων έχουν αδένες που εκκρίνουν απωθητικές η δηλητηριώδεις ουσίες. Οι τοξίνες ορισμένων αμφιβίων μπορεί να είναι θανατηφόρες για τον άνθρωπο ενώ άλλες έχουν ελάχιστες επιπτώσεις.[51] Οι κύριοι δηλητηριώδεις αδένες, οι παρώτιοι αδένες (ή παρωτιδικοί), παράγουν την νευροτοξίνη μπουφοτοξίνη και βρίσκονται πίσω από τα αυτιά των φρύνων, κατα μήκος της ράχης των βατράχων, πίσω από τους οφθαλμούς των σαλαμανδρών και στην επάνω επιφάνεια των απόδων.[52]

Το χρώμα του δέρματος των αμφιβίων παράγεται από τρία στρώματα χρωματοφόρων κυττάρων. Αυτά τα τρία κυτταρικά στρώματα αποτελούνται από τα μελανοφόρα (βαθύτερο στρώμα), τα γκουανοφόρα (σχηματίζουν ένα ενδιάμεσο στρώμα και περιλαμβάνουν πολλούς κόκκους, που παράγουν ένα μπλε-πράσινο χρώμα) και τα λιποφόρα (κίτρινα, το ανώτερο στρώμα). Η αλλάγές χρωμάτων που εμφανίζουν πολλά είδη ελέγχονται από ορμόνες που εκκρίνονται από την υπόφυση. Αντίθετα από τους οστεϊχθύες, δεν υπάρχει άμεσος έλεγχος των χρωματοφόρων από το νευρικόσ ύστημα, με αποτέλεσμα η αλλαγή χρώματος να είναι βραδύτερη από αυτή των ιχθύων. Οι ζωηροί χρωματισμοί του δέρματος συνήθως υποδεικνύουν ότι το είδος είναι τοξικό και αποτελούν προειδοποιητικό σημείο για τους θηρευτές.[53]

Σκελετικό σύστημα και κίνηση[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Τα αμφίβια έχουν σκελετικό σύστημα το οποίο είναι δομικά ομόλογο με τα άλλα τετράποδα, αν και με κάποιες διαφοροποιήσεις. Όλα έχουν τέσσερα άκρα εκτός των απόδων καικιλίων και λίγων ειδών σαλαμανδρών με λιγότερα ή καθόλου άκρα. Τα οστά είναι κοίλα και ελαφριά. Το μυοσκελετικό σύστημα είναι ισχυρό έτσι, ώστε επιτρέπει την στήριξη της κεφαλής και του κορμού. Τα οστά είναι πλήρως οστεοποιημένα. Η ωμική ζώνη υποστηρίζεται από μύες και η καλά ανεπτυγμένη πυελική ζώνη συνδέεται με την σπονδυλική στήλη μέσω του ιερού οστού. Το λαγόνιο κλίνει προς τα εμπρός και το σώμα κρατιέται πλησιέστερα στο έδφος από ότι στα θηλαστικά.[54]

(Ceratophrys cornuta)

Στα περισσότερα αμφίβια, υπάρχουν τέσσερα δάκτυλα στα μπροστινά άκρα και πέντε στα οπίσθια άκρα, αλλά πουθενά γαμψώνυχες. Κάποιες σαλαμάνδρες έχουν λιγότερα δάκτυλα και το Αμφιούμα που μοιάζει με χέλι έχει μικροσκοπικά, κοντόχοντρα πόδια. Οι σειρήνες είναι υδρόβιες σαλαμάνδρες με κοντόχοντρα μπροστινά πόδια και χωρίς οπίσθια άκρα. Οι καικιλίες είναι άποδοι. Ανοίγουν λαγούμια όπως οι γεωσκώληκες με ζώνες μυϊκών συστολών που κινούνται κατά μήκος του σώματος. Στην επιφάνεια του εδάφους ή στο νερό κινούνται με κυματισμούς του σώματός τους.[55]

Στους βατράχους, τα πίσω πόδια είναι μεγαλύτερα από τα μπροστινά, ιδιαίτερα στα είδη αυτά που κινούνται κυρίως με άλματα ή κολυμπώντας. Στα είδη που βαδίζουν ή τρέχουν τα πίσω πόδια δεν είναι τόσο μεγάλα και τα είδη που σκάβουν λαγούμια έχουν κατά κόρον κοντά άκρα και φαρδύ κορμό. Τα πόδια είναι προσαρμοσμένα στον τρόπο ζωής με νηκτικές μεμβράνες μεταξύ των δακτύλων για κολύμβηση, πλατιά κολλώδη πέλματα για αναρρίχηση και κερατινοποιημένα φύματα στα πίσω πόδια για σκάψιμο (οι βάτραχοι συνήθως σκάβουν στο χώμα προς τα πίσω). Στις περισσότερες σαλαμάνδρες, τα άκρα είναι κοντά και περισσότερο ή λιγότερο ισομήκη και προεκβάλλουν σε ορθές γωνίες με το σώμα. Η κίνηση στην ξηρά πραγματοποείται με βάδισμα και η ουρά συχνά αιωρείται από τη μία πλευρά στην άλλη ή χρησιμοποείται ως στήριγμα, ιδιαιτέρως όταν σκαρφαλώνουν. Σε κανονικό βάδισμα, μονάχα ένα πόδι αφήνει το έδαφος κάθε φορά με τον τρόπο που είχαν προσαρμοστεί οι πρόγονοί τους, οι Σαρκοπτερύγιοι.[54] Κάποιες σαλαμάνδρες του γένους Ανειδής και ορισμένοι Πληθοδοντίδες αναρριχώνται στα δένδρα και έχουν επιμήκη πόδια, μεγάλα πέλματα και συλληπτήρια ουρά.[45] Στις υδρόβιες σλαμάνδρες και στους υρίνους των βατράχων, η ουρά έχει ραχιαία και κοιλιακά περύγιο και κινείται από την μία στην άλλη πλευρά ως μέσο προώθησης. Οι ενήλικοι βάτραχοι δεν έχουν ουρές και οι καικιλίες έχουν πολύ κοντές.[55]

Salamanders use their tails in defence and some are prepared to jettison them to save their lives in a process known as autotomy. Certain species in the Plethodontidae have a weak zone at the base of the tail and use this strategy readily. The tail often continues to twitch after separation which may distract the attacker and allow the salamander to escape. Both tails and limbs can be regenerated.[56] Adult frogs are unable to regrow limbs but tadpoles can do so.[55]

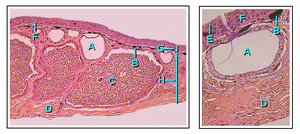

Circulatory system[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

1 – Internal gills where the blood is reoxygenated

2 – Point where the blood is depleted of oxygen and returns to the heart via veins

3 – Two chambered heart.

Red indicates oxygenated blood, and blue represents oxygen depleted blood.

Amphibians have a juvenile stage and an adult stage, and the circulatory systems of the two are distinct. In the juvenile (or tadpole) stage, the circulation is similar to that of a fish; the two-chambered heart pumps the blood through the gills where it is oxygenated, around the body and back to the heart in a single loop. In the adult stage, amphibians (especially frogs) lose their gills and develop lungs. They have a heart that consists of a single ventricle and two atria. When the ventricle starts contracting, deoxygenated blood is pumped through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. Continued contraction then pumps oxygenated blood around the rest of the body. Mixing of the two bloodstreams is minimized by the anatomy of the chambers.[57]

Nervous and sensory systems[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

The nervous system is basically the same as in other vertebrates, with a central brain, a spinal cord, and nerves throughout the body. The amphibian brain is less well developed than that of reptiles, birds and mammals but is similar in morphology and function to that of a fish. It consists of equal parts cerebrum, midbrain and cerebellum. Various parts of the cerebrum process sensory input, such as smell in the olfactory lobe and sight in the optic lobe, and it is additionally the centre of behaviour and learning. The cerebellum is the centre of muscular coordination and the medulla oblongata controls some organ functions including heartbeat and respiration. The brain sends signals through the spinal cord and nerves to regulate activity in the rest of the body. The pineal body, known to regulate sleep patterns in humans, is thought to produce the hormones involved in hibernation and aestivation in amphibians.[58]

Tadpoles retain the lateral line system of their ancestral fishes, but this is lost in terrestrial adult amphibians. Some caecilians possess electroreceptors that allow them to locate objects around them when submerged in water. The ears are well developed in frogs. There is no external ear, but the large circular eardrum lies on the surface of the head just behind the eye. This vibrates and sound is transmitted through a single bone, the stapes, to the inner ear. Only high-frequency sounds like mating calls are heard in this way, but low-frequency noises can be detected through another mechanism.[54] There is a patch of specialized haircells, called papilla amphibiorum, in the inner ear capable of detecting deeper sounds. Another feature, unique to frogs and salamanders, is the columella-operculum complex adjoining the auditory capsule which is involved in the transmission of both airborne and seismic signals.[59] The ears of salamanders and caecilians are less highly developed than those of frogs as they do not normally communicate with each other through the medium of sound.[60]

The eyes of tadpoles lack lids, but at metamorphosis, the cornea becomes more dome-shaped, the lens becomes flatter, and eyelids and associated glands and ducts develop.[54] The adult eyes are an improvement on invertebrate eyes and were a first step in the development of more advanced vertebrate eyes. They allow colour vision and depth of focus. In the retinas are green rods, which are receptive to a wide range of wavelengths.[60]

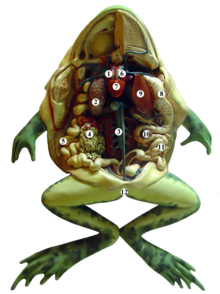

Digestive and excretory systems[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Many amphibians catch their prey by flicking out an elongated tongue with a sticky tip and drawing it back into the mouth before seizing the item with their jaws. Some use inertial feeding to help them swallow the prey, repeatedly thrusting their head forward sharply causing the food to move backwards in their mouth by inertia. Most amphibians swallow their prey whole without much chewing so they possess voluminous stomachs. The short oesophagus is lined with cilia that help to move the food to the stomach and mucus produced by glands in the mouth and pharynx eases its passage. The enzyme chitinase produced in the stomach helps digest the chitinous cuticle of arthropod prey.[61]

Amphibians possess a pancreas, liver and gall bladder. The liver is usually large with two lobes. Its size is determined by its function as a glycogen and fat storage unit, and may change with the seasons as these reserves are built or used up. Adipose tissue is another important means of storing energy and this occurs in the abdomen, under the skin and, in some salamanders, in the tail.[62]

There are two kidneys located dorsally, near the roof of the body cavity. Their job is to filter the blood of metabolic waste and transport the urine via ureters to the urinary bladder where it is stored before being passed out periodically through the cloacal vent. Larvae and most aquatic adult amphibians excrete the nitrogen as ammonia in large quantities of dilute urine, while terrestrial species, with a greater need to conserve water, excrete the less toxic product urea. Some tree frogs with limited access to water excrete most of their metabolic waste as uric acid.[63]

Respiratory system[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

The lungs in amphibians are primitive compared to those of amniotes, possessing few internal septa and large alveoli, and consequently having a comparatively slow diffusion rate for oxygen entering the blood. Ventilation is accomplished by buccal pumping.[64] Most amphibians, however, are able to exchange gases with the water or air via their skin. To enable sufficient cutaneous respiration, the surface of their highly vascularised skin must remain moist to allow the oxygen to diffuse at a sufficiently high rate.[61] Because oxygen concentration in the water increases at both low temperatures and high flow rates, aquatic amphibians in these situations can rely primarily on cutaneous respiration, as in the Titicaca water frog and the hellbender salamander. In air, where oxygen is more concentrated, some small species can rely solely on cutaneous gas exchange, most famously the plethodontid salamanders, which have neither lungs nor gills. Many aquatic salamanders and all tadpoles have gills in their larval stage, with some (such as the axolotl) retaining gills as aquatic adults.[61]

Reproduction[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

For the purpose of reproduction most amphibians require fresh water although some lay their eggs on land and have developed various means of keeping them moist. A few (e.g. Fejervarya raja) can inhabit brackish water, but there are no true marine amphibians.[65] There are reports, however, of particular amphibian populations unexpectedly invading marine waters. Such was the case with the Black Sea invasion of the natural hybrid Pelophylax esculentus reported in 2010.[66]

Several hundred frog species in adaptive radiations (e.g., Eleutherodactylus, the Pacific Platymantines, the Australo-Papuan microhylids, and many other tropical frogs), however, do not need any water for breeding in the wild. They reproduce via direct development, an ecological and evolutionary adaptation that has allowed them to be completely independent from free-standing water. Almost all of these frogs live in wet tropical rainforests and their eggs hatch directly into miniature versions of the adult, passing through the tadpole stage within the egg. Reproductive success of many amphibians is dependent not only on the quantity of rainfall, but the seasonal timing.[67]

In the tropics, many amphibians breed continuously or at any time of year. In temperate regions, breeding is mostly seasonal, usually in the spring, and is triggered by increasing day length, rising temperatures or rainfall. Experiments have shown the importance of temperature, but the trigger event, especially in arid regions, is often a storm. In anurans, males usually arrive at the breeding sites before females and the vocal chorus they produce may stimulate ovulation in females and the endocrine activity of males that are not yet reproductively active.[68]

In caecilians, fertilisation is internal, the male extruding an intromittent organ, the phallodeum, and inserting it into the female cloaca. The paired Müllerian glands inside the male cloaca secrete a fluid which resembles that produced by mammalian prostate glands and which may transport and nourish the sperm. Fertilisation probably takes place in the oviduct.[69]

The majority of salamanders also engage in internal fertilisation. In most of these, the male deposits a spermatophore, a small packet of sperm on top of a gelatinous cone, on the substrate either on land or in the water. The female takes up the sperm packet by grasping it with the lips of the cloaca and pushing it into the vent. The spermatozoa move to the spermatheca in the roof of the cloaca where they remain until ovulation which may be many months later. Courtship rituals and methods of transfer of the spermatophore vary between species. In some, the spermatophore may be placed directly into the female cloaca while in others, the female may be guided to the spermatophore or restrained with an embrace called amplexus. Certain primitive salamanders in the families Sirenidae, Hynobiidae and Cryptobranchidae practice external fertilisation in a similar manner to frogs, with the female laying the eggs in water and the male releasing sperm onto the egg mass.[69]

With a few exceptions, frogs use external fertilisation. The male grasps the female tightly with his forelimbs either behind the arms or in front of the back legs, or in the case of Epipedobates tricolor, around the neck. They remain in amplexus with their cloacae positioned close together while the female lays the eggs and the male covers them with sperm. Roughened nuptial pads on the male's hands aid in retaining grip. Often the male collects and retains the egg mass, forming a sort of basket with the hind feet. An exception is the granular poison frog (Oophaga granulifera) where the male and female place their cloacae in close proximity while facing in opposite directions and then release eggs and sperm simultaneously. The tailed frog (Ascaphus truei) exhibits internal fertilisation. The "tail" is only possessed by the male and is an extension of the cloaca and used to inseminate the female. This frog lives in fast-flowing streams and internal fertilisation prevents the sperm from being washed away before fertilisation occurs.[70] The sperm may be retained in storage tubes attached to the oviduct until the following spring.[71]

Most frogs can be classified as either prolonged or explosive breeders. Typically, prolonged breeders congregate at a breeding site, the males usually arriving first, calling and setting up territories. Other satellite males remain quietly nearby, waiting for their opportunity to take over a territory. The females arrive sporadically, mate selection takes place and eggs are laid. The females depart and territories may change hands. More females appear and in due course, the breeding season comes to an end. Explosive breeders on the other hand are found where temporary pools appear in dry regions after rainfall. These frogs are typically fossorial species that emerge after heavy rains and congregate at a breeding site. They are attracted there by the calling of the first male to find a suitable place, perhaps a pool that forms in the same place each rainy season. The assembled frogs may call in unison and frenzied activity ensues, the males scrambling to mate with the usually smaller number of females.[70]

Life cycle[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Most amphibians go through metamorphosis, a process of significant morphological change after birth. In typical amphibian development, eggs are laid in water and larvae are adapted to an aquatic lifestyle. Frogs, toads and salamanders all hatch from the egg as larvae with external gills. Metamorphosis in amphibians is regulated by thyroxine concentration in the blood, which stimulates metamorphosis, and prolactin, which counteracts thyroxine's effect. Specific events are dependent on threshold values for different tissues.[72] Because most embryonic development is outside the parental body, it is subject to many adaptations due to specific environmental circumstances. For this reason tadpoles can have horny ridges instead of teeth, whisker-like skin extensions or fins. They also make use of a sensory lateral line organ similar to that of fish. After metamorphosis, these organs become redundant and will be reabsorbed by controlled cell death, called apoptosis. The variety of adaptations to specific environmental circumstances among amphibians is wide, with many discoveries still being made.[73]

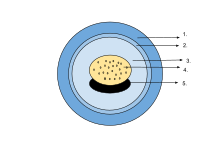

Eggs[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

1. Jelly capsule 2. Vitelline membrane

3. Perivitelline fluid 4. Yolk plug

5. Embryo

The egg of an amphibian is typically surrounded by a transparent gelatinous covering secreted by the oviducts and containing mucoproteins and mucopolysaccharides. This capsule is permeable to water and gases, and swells considerably as it absorbs water. The ovum is at first rigidly held, but in fertilised eggs the innermost layer liquefies and allows the embryo to move freely. This also happens in salamander eggs, even when they are unfertilised. Eggs of some salamanders and frogs contain unicellular green algae. These penetrate the jelly envelope after the eggs are laid and may increase the supply of oxygen to the embryo through photosynthesis. They seem to both speed up the development of the larvae and reduce mortality.[74] Most eggs contain the pigment melanin which raises their temperature through the absorption of light and also protects them against ultraviolet radiation. Caecilians, some plethodontid salamanders and certain frogs that lay eggs underground have unpigmented eggs. In the wood frog (Rana sylvatica), the interior of the globular egg cluster has been found to be up to 6 °C (43 °F) warmer than its surroundings which is an advantage in its cool northern habitat.[75]

The eggs may be deposited singly or in small groups, or may take the form of spherical egg masses, rafts or long strings. In terrestrial caecilians, the eggs are laid in grape-like clusters in burrows near streams. The amphibious salamander Ensatina attaches its similar clusters by stalks to underwater stems and roots. The greenhouse frog (Eleutherodactylus planirostris) lays eggs in small groups in the soil where they develop in about two weeks directly into juvenile frogs without an intervening larval stage.[76] The tungara frog (Physalaemus pustulosus) builds a floating nest from foam to protect its eggs. First a raft is built, then eggs are laid in the centre, and finally a foam cap is overlaid. The foam has anti-microbial properties. It contains no detergents but is created by whipping up proteins and lectins secreted by the female.[77][78]

Larvae[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

The eggs of amphibians are typically laid in water and hatch into free-living larvae that complete their development in water and later transform into either aquatic or terrestrial adults. In many species of frog and in most lungless salamanders (Plethodontidae), direct development takes place, the larvae growing within the eggs and emerging as miniature adults. Many caecilians and some other amphibians lay their eggs on land, and the newly hatched larvae wriggle or are transported to water bodies. Some caecilians, the Alpine salamander (Salamandra atra) and some of the African live-bearing toads (Nectophrynoides spp.) are viviparous. Their larvae feed on glandular secretions and develop within the female's oviduct, often for long periods. Other amphibians, but not caecilians, are ovoviviparous. The eggs are retained in or on the parent's body, but the larvae subsist on the yolks of their eggs and receive no nourishment from the adult. The larvae emerge at varying stages of their growth, either before or after metamorphosis, according to their species.[79] The toad genus Nectophrynoides exhibits all of these developmental patterns among its dozen or so members.[6]

Frogs[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Frog larvae are known as tadpoles and typically have oval bodies and long, vertically flattened tails with fins. The free-living larvae are normally fully aquatic, but the tadpoles of some species such as (Nannophrys ceylonensis) are semi-terrestrial and live among wet rocks.[80] Tadpoles have cartilaginous skeletons, gills for respiration (external gills at first, internal gills later), lateral line systems and large tails that they use for swimming.[81] Newly hatched tadpoles soon develop gill pouches that cover the gills. The lungs develop early and are used as accessory breathing organs, the tadpoles rising to the water surface to gulp air. Some species complete their development inside the egg and hatch directly into small frogs. These larvae do not have gills but instead have specialised areas of skin through which respiration takes place. While tadpoles do not have true teeth, in most species, the jaws have long, parallel rows of small keratinized structures called keradonts surrounded by a horny beak.[82] Front legs are formed under the gill sac and hind legs become visible a few days later. Tadpoles are typically herbivorous, feeding mostly on algae, including diatoms filtered from the water through the gills. They are also detritivores, stirring up the sediment at the pond bottom and ingesting edible fragments. They have a relatively long, spiral-shaped gut to enable them to digest this diet.[83] Some species are carnivorous at the tadpole stage, eating insects, smaller tadpoles and fish. Young of the Cuban tree frog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) can occasionally be cannibalistic, the younger tadpoles attacking a larger, more developed tadpole when it is undergoing metamorphosis.[84]

At metamorphosis, rapid changes in the body take place as the lifestyle of the frog changes completely. The spiral‐shaped mouth with horny tooth ridges is reabsorbed together with the spiral gut. The animal develops a large jaw, and its gills disappear along with its gill sac. Eyes and legs grow quickly, and a tongue is formed. There are associated changes in the neural networks such as development of stereoscopic vision and loss of the lateral line system. All this can happen in about a day. A few days later, the tail is reabsorbed, due to the higher thyroxine concentration required for this to take place.[83]

Salamanders[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

(Ambystoma macrodactylum)

(Ichthyosaura alpestris)

At hatching, a typical salamander larva has eyes without lids, teeth in both upper and lower jaws, three pairs of feathery external gills, a somewhat laterally flattened body and a long tail with dorsal and ventral fins. The forelimbs may be partially developed and the hind limbs are rudimentary in pond-living species but may be rather more developed in species that reproduce in moving water. Pond-type larvae often have a pair of balancers, rod-like structures on either side of the head that may prevent the gills from becoming clogged up with sediment. Some members of the genera Ambystoma and Dicamptodon have larvae that never fully develop into the adult form, but this varies with species and with populations. The northwestern salamander (Ambystoma gracile) is one of these and, depending on environmental factors, either remains permanently in the larval state, a condition known as neoteny, or transforms into an adult.[85] Both of these are able to breed.[86] Neoteny occurs when the animal's growth rate is very low and is usually linked to adverse conditions such as low water temperatures that may change the response of the tissues to the hormone thyroxine.[87] Other factors that may inhibit metamorphosis include lack of food, lack of trace elements and competition from conspecifics. The tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) also sometimes behaves in this way and may grow particularly large in the process. The adult tiger salamander is terrestrial, but the larva is aquatic and able to breed while still in the larval state. When conditions are particularly inhospitable on land, larval breeding may allow continuation of a population that would otherwise die out. There are fifteen species of obligate neotenic salamanders, including species of Necturus, Proteus and Amphiuma, and many examples of facultative ones that adopt this strategy under appropriate environmental circumstances.[88]

Lungless salamanders in the family Plethodontidae are terrestrial and lay a small number of unpigmented eggs in a cluster among damp leaf litter. Each egg has a large yolk sac and the larva feeds on this while it develops inside the egg, emerging fully formed as a juvenile salamander. The female salamander often broods the eggs. In the genus Ensatinas, the female has been observed to coil around them and press her throat area against them, effectively massaging them with a mucous secretion.[89]

In newts and salamanders, metamorphosis is less dramatic than in frogs. This is because the larvae are already carnivorous and continue to feed as predators when they are adults so few changes are needed to their digestive systems. Their lungs are functional early, but the larvae don't make as much use of them as do tadpoles. Their gills are never covered by gill sacs and are reabsorbed just before the animals leave the water. Other changes include the reduction in size or loss of tail fins, the closure of gill slits, thickening of the skin, the development of eyelids, and certain changes in dentition and tongue structure. Salamanders are at their most vulnerable at metamorphosis as swimming speeds are reduced and transforming tails are encumbrances on land.[90] Adult salamanders often have an aquatic phase in spring and summer, and a land phase in winter. For adaptation to a water phase, prolactin is the required hormone, and for adaptation to the land phase, thyroxine. External gills do not return in subsequent aquatic phases because these are completely absorbed upon leaving the water for the first time.[91]

Caecilians[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Most terrestrial caecilians that lay eggs do so in burrows or moist places on land near bodies of water. The development of the young of Ichthyophis glutinosus, a species from Sri Lanka, has been much studied. The eel-like larvae hatch out of the eggs and make their way to water. They have three pairs of external red feathery gills, a blunt head with two rudimentary eyes, a lateral line system and a short tail with fins. They swim by undulating their body from side to side. They are mostly active at night, soon lose their gills and make sorties onto land. Metamorphosis is gradual. By the age of about ten months they have developed a pointed head with sensory tentacles near the mouth and lost their eyes, lateral line systems and tails. The skin thickens, embedded scales develop and the body divides into segments. By this time, the caecilian has constructed a burrow and is living on land.[92]

In the majority of species of caecilians, the young are produced by vivipary. Typhlonectes compressicauda, a species from South America, is typical of these. Up to nine larvae can develop in the oviduct at any one time. They are elongated and have paired sac-like gills, small eyes and specialised scraping teeth. At first, they feed on the yolks of the eggs, but as this source of nourishment declines they begin to rasp at the ciliated epithelial cells that line the oviduct. This stimulates the secretion of fluids rich in lipids and mucoproteins on which they feed along with scrapings from the oviduct wall. They may increase their length sixfold and be two-fifths as long as their mother before being born. By this time they have undergone metamorphosis, lost their eyes and gills, developed a thicker skin and mouth tentacles, and reabsorbed their teeth. A permanent set of teeth grow through soon after birth.[93][94]

The ringed caecilian (Siphonops annulatus) has developed a unique adaptation for the purposes of reproduction. The progeny feed on a skin layer that is specially developed by the adult in a phenomenon known as maternal dermatophagy. The brood feed as a batch for about seven minutes at intervals of approximately three days which gives the skin an opportunity to regenerate. Meanwhile, they have been observed to ingest fluid exuded from the maternal cloaca.[95]

Parental care[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

The care of offspring among amphibians has been little studied but, in general, the larger the number of eggs in a batch, the less likely it is that any degree of parental care takes place. Nevertheless, it is estimated that in up to 20% of amphibian species, one or both adults play some role in the care of the young.[96] Those species that breed in smaller water bodies or other specialised habitats tend to have complex patterns of behaviour in the care of their young.[97]

Many woodland salamanders lay clutches of eggs under dead logs or stones on land. The black mountain salamander (Desmognathus welteri) does this, the mother brooding the eggs and guarding them from predation as the embryos feed on the yolks of their eggs. When fully developed, they break their way out of the egg capsules and disperse as juvenile salamanders.[98] The male hellbender, a primitive salamander, excavates an underwater nest and encourages females to lay there. The male then guards the site for the two or three months before the eggs hatch, using body undulations to fan the eggs and increase their supply of oxygen.[44]

The male Colostethus subpunctatus, a tiny frog, protects the egg cluster which is hidden under a stone or log. When the eggs hatch, the male transports the tadpoles on his back, stuck there by a mucous secretion, to a temporary pool where he dips himself into the water and the tadpoles drop off.[99] The male midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) winds egg strings round his thighs and carries the eggs around for up to eight weeks. He keeps them moist and when they are ready to hatch, he visits a pond or ditch and releases the tadpoles.[100] The female gastric-brooding frog (Rheobatrachus spp.) reared larvae in her stomach after swallowing either the eggs or hatchlings; however, this stage was never observed before the species became extinct. The tadpoles secrete a hormone that inhibits digestion in the mother whilst they develop by consuming their very large yolk supply.[101] The pouched frog (Assa darlingtoni) lays eggs on the ground. When they hatch, the male carries the tadpoles around in brood pouches on his hind legs.[102] The aquatic Surinam toad (Pipa pipa) raises its young in pores on its back where they remain until metamorphosis.[103] The granular poison frog (Oophaga granulifera) is typical of a number of tree frogs in the poison dart frog family Dendrobatidae. Its eggs are laid on the forest floor and when they hatch, the tadpoles are carried one by one on the back of an adult to a suitable water-filled crevice such as the axil of a leaf or the rosette of a bromeliad. The female visits the nursery sites regularly and deposits unfertilised eggs in the water and these are consumed by the tadpoles.[104]

Feeding and diet[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

(Ambystoma gracile) eating a worm

With a few exceptions, adult amphibians are predators, feeding on virtually anything that moves that they can swallow. The diet mostly consists of small prey that do not move too fast such as beetles, caterpillars, earthworms and spiders. The sirens (Siren spp.) often ingest aquatic plant material with the invertebrates on which they feed[105] and a Brazilian tree frog Xenohyla truncata includes a large quantity of fruit in its diet.[106] The Mexican burrowing toad (Rhinophrynus dorsalis) has a specially adapted tongue for picking up ants and termites. It projects it with the tip foremost whereas other frogs flick out the rear part first, their tongues being hinged at the front.[107]

Food is mostly selected by sight, even in conditions of dim light. Movement of the prey triggers a feeding response. Frogs have been caught on fish hooks baited with red flannel and green frogs (Rana clamitans) have been found with stomachs full of elm seeds that they had seen floating past.[108] Toads, salamanders and caecilians also use smell to detect prey. This response is mostly secondary because salamanders have been observed to remain stationary near odoriferous prey but only feed if it moves. Cave-dwelling amphibians normally hunt by smell. Some salamanders seem to have learned to recognize immobile prey when it has no smell, even in complete darkness.[109]

Amphibians usually swallow food whole but may chew it lightly first to subdue it.[34] They typically have small hinged pedicellate teeth, a feature unique to amphibians. The base and crown of these are composed of dentine separated by an uncalcified layer and they are replaced at intervals. Salamanders, caecilians and some frogs have one or two rows of teeth in both jaws, but some frogs (Rana spp.) lack teeth in the lower jaw, and toads (Bufo spp.) have no teeth. In many amphibians there are also vomerine teeth attached to a facial bone in the roof of the mouth.[110]

The tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) is typical of the frogs and salamanders that hide under cover ready to ambush unwary invertebrates. Others amphibians, such as the Bufo spp. toads, actively search for prey, while the Argentine horned frog (Ceratophrys ornata) lures inquisitive prey closer by raising its hind feet over its back and vibrating its yellow toes.[111] Among leaf litter frogs in Panama, frogs that actively hunt prey have narrow mouths and are slim, often brightly coloured and toxic, while ambushers have wide mouths and are broad and well-camouflaged.[112] Caecilians do not flick their tongues, but catch their prey by grabbing it with their slightly backward-pointing teeth. The struggles of the prey and further jaw movements work it inwards and the caecilian usually retreats into its burrow. The subdued prey is gulped down whole.[113]

When they are newly hatched, frog larvae feed on the yolk of the egg. When this is exhausted some move on to feed on bacteria, algal crusts, detritus and raspings from submerged plants. Water is drawn in through their mouths, which are usually at the bottom of their heads, and passes through branchial food traps between their mouths and their gills where fine particles are trapped in mucus and filtered out. Others have specialised mouthparts consisting of a horny beak edged by several rows of labial teeth. They scrape and bite food of many kinds as well as stirring up the bottom sediment, filtering out larger particles with the papillae around their mouths. Some, such as the spadefoot toads, have strong biting jaws and are carnivorous or even cannibalistic.[114]

Vocalization[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

The calls made by caecilians and salamanders are limited to occasional soft squeaks, grunts or hisses and have not been much studied. A clicking sound sometimes produced by caecilians may be a means of orientation, as in bats, or a form of communication. Most salamanders are considered voiceless, but the California giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus) has vocal cords and can produce a rattling or barking sound. Some species of salamander emit a quiet squeak or yelp if attacked.[115]

Frogs are much more vocal, especially during the breeding season when they use their voices to attract mates. The presence of a particular species in an area may be more easily discerned by its characteristic call than by a fleeting glimpse of the animal itself. In most species, the sound is produced by expelling air from the lungs over the vocal cords into an air sac or sacs in the throat or at the corner of the mouth. This may distend like a balloon and acts as a resonator, helping to transfer the sound to the atmosphere, or the water at times when the animal is submerged.[115] The main vocalisation is the male's loud advertisement call which seeks to both encourage a female to approach and discourage other males from intruding on its territory. This call is modified to a quieter courtship call on the approach of a female or to a more aggressive version if a male intruder draws near. Calling carries the risk of attracting predators and involves the expenditure of much energy.[116] Other calls include those given by a female in response to the advertisement call and a release call given by a male or female during unwanted attempts at amplexus. When a frog is attacked, a distress or fright call is emitted, often resembling a scream.[117] The usually nocturnal Cuban tree frog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) produces a rain call when there is rainfall during daylight hours.[118]

Territorial behaviour[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Little is known of the territorial behaviour of caecilians, but some frogs and salamanders defend home ranges. These are usually feeding, breeding or sheltering sites. Males normally exhibit such behaviour though in some species, females and even juveniles are also involved. Although in many frog species, females are larger than males, this is not the case in most species where males are actively involved in territorial defence. Some of these have specific adaptations such as enlarged teeth for biting or spines on the chest, arms or thumbs.[119]

In salamanders, defence of a territory involves adopting an aggressive posture and if necessary attacking the intruder. This may involve snapping, chasing and sometimes biting, occasionally causing the loss of a tail. The behaviour of red back salamanders (Plethodon cinereus) has been much studied. 91% of marked individuals that were later recaptured were within a metre (yard) of their original daytime retreat under a log or rock.[120] A similar proportion, when moved experimentally a distance of 30 metres (98 ft), found their way back to their home base.[120] The salamanders left odour marks around their territories which averaged 0,16 to 0,33 square metres (1,7 to 3,6 sq ft) in size and were sometimes inhabited by a male and female pair.[121] These deterred the intrusion of others and delineated the boundaries between neighbouring areas. Much of their behaviour seemed stereotyped and did not involve any actual contact between individuals. An aggressive posture involved raising the body off the ground and glaring at the opponent who often turned away submissively. If the intruder persisted, a biting lunge was usually launched at either the tail region or the naso-labial grooves. Damage to either of these areas can reduce the fitness of the rival, either because of the need to regenerate tissue or because it impairs its ability to detect food.[120]

In frogs, male territorial behaviour is often observed at breeding locations; calling is both an announcement of ownership of part of this resource and an advertisement call to potential mates. In general, a deeper voice represents a heavier and more powerful individual, and this may be sufficient to prevent intrusion by smaller males. Much energy is used in the vocalization and it takes a toll on the territory holder who may be displaced by a fitter rival if he tires. There is a tendency for males to tolerate the holders of neighbouring territories while vigorously attacking unknown intruders. Holders of territories have a "home advantage" and usually come off better in an encounter between two similar-sized frogs. If threats are insufficient, chest to chest tussles may take place. Fighting methods include pushing and shoving, deflating the opponent's vocal sac, seizing him by the head, jumping on his back, biting, chasing, splashing, and ducking him under the water.[122]

Defence mechanisms[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Amphibians have soft bodies with thin skins, and lack claws, defensive armour, or spines. Nevertheless, they have evolved various defence mechanisms to keep themselves alive. The first line of defence in salamanders and frogs is the mucous secretion that they produce. This keeps their skin moist and makes them slippery and difficult to grip. The secretion is often sticky and distasteful or toxic.[123] Snakes have been observed yawning and gaping when trying to swallow African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis), which gives the frogs an opportunity to escape.[123][124] Caecilians have been little studied in this respect, but the Cayenne caecilian (Typhlonectes compressicauda) produces toxic mucus that has killed predatory fish in a feeding experiment in Brazil.[125] In some salamanders, the skin is poisonous. The rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) from North America and other members of its genus contain the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin (TTX), the most toxic non-protein substance known and almost identical to that produced by pufferfish. Handling the newts does not cause harm, but ingestion of even the most minute amounts of the skin is deadly. In feeding trials, fish, frogs, reptiles, birds and mammals were all found to be susceptible.[126][127] The only predators with some tolerance to the poison are certain populations of common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis). In locations where both snake and salamander co-exist, the snakes have developed immunity through genetic changes and they feed on the amphibians with impunity.[128] Coevolution occurs with the newt increasing its toxic capabilities at the same rate as the snake further develops its immunity.[127] Some frogs and toads are toxic, the main poison glands being at the side of the neck and under the warts on the back. These regions are presented to the attacking animal and their secretions may be foul-tasting or cause various physical or neurological symptoms. Altogether, over 200 toxins have been isolated from the limited number of amphibian species that have been investigated.[129]

Poisonous species often use bright colouring to warn potential predators of their toxicity. These warning colours tend to be red or yellow combined with black, with the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) being an example. Once a predator has sampled one of these, it is likely to remember the colouration next time it encounters a similar animal. In some species, such as the fire-bellied toad (Bombina spp.), the warning colouration is on the belly and these animals adopt a defensive pose when attacked, exhibiting their bright colours to the predator. The frog Allobates zaparo is not poisonous, but mimics the appearance of other toxic species in its locality, a strategy that may deceive predators.[131]

Many amphibians are nocturnal and hide during the day, thereby avoiding diurnal predators that hunt by sight. Other amphibians use camouflage to avoid being detected. They have various colourings such as mottled browns, greys and olives to blend into the background. Some salamanders adopt defensive poses when faced by a potential predator such as the North American northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda). Their bodies writhe and they raise and lash their tails which makes it difficult for the predator to avoid contact with their poison-producing granular glands.[132] A few salamanders will autotomise their tails when attacked, sacrificing this part of their anatomy to enable them to escape. The tail may have a constriction at its base to allow it to be easily detached. The tail is regenerated later, but the energy cost to the animal of replacing it is significant.[133]

Some frogs and toads inflate themselves to make themselves look large and fierce, and some spadefoot toads (Pelobates spp) scream and leap towards the attacker.[34] Giant salamanders of the genus Andrias, as well as Ceratophrine and Pyxicephalus frogs possess sharp teeth and are capable of drawing blood with a defensive bite. The blackbelly salamander (Desmognathus quadramaculatus) can bite an attacking common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) two or three times its size on the head and often manages to escape.[134]

Conservation[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

Dramatic declines in amphibian populations, including population crashes and mass localized extinction, have been noted since the late 1980s from locations all over the world, and amphibian declines are thus perceived to be one of the most critical threats to global biodiversity.[135] In 2004, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reported stating that currently birds,[136] mammals, and amphibians extinction rates were at maximum 48 times greater than natural extinction rates—possibly 1,024 times higher. In 2006 there were believed to be 4,035 species of amphibians that depended on water at some stage during their life cycle. Of these, 1,356 (33.6%) were considered to be threatened and this figure is likely to be an underestimate because it excludes 1,427 species for which there was insufficient data to assess their status.[137] A number of causes are believed to be involved, including habitat destruction and modification, over-exploitation, pollution, introduced species, climate change, endocrine-disrupting pollutants, destruction of the ozone layer (ultraviolet radiation has shown to be especially damaging to the skin, eyes, and eggs of amphibians), and diseases like chytridiomycosis. However, many of the causes of amphibian declines are still poorly understood, and are a topic of ongoing discussion.[138]

With their complex reproductive needs and permeable skins, amphibians are often considered to be ecological indicators.[139] In many terrestrial ecosystems, they constitute one of the largest parts of the vertebrate biomass. Any decline in amphibian numbers will have an impact on the patterns of predation. The loss of carnivorous species near the top of the food chain will upset the delicate ecosystem balance and may cause dramatic increases in opportunistic species. In the Middle East, a growing appetite for eating frog legs and the consequent gathering of them for food was linked to an increase in mosquitoes.[140] Predators that feed on amphibians are affected by their decline. The western terrestrial garter snake (Thamnophis elegans) in California is largely aquatic and depends heavily on two species of frog that are diminishing in numbers, the Yosemite toad (Bufo canorus) and the mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa), putting the snake's future at risk. If the snake were to become scarce, this would affect birds of prey and other predators that feed on it.[141] Meanwhile, in the ponds and lakes, fewer frogs means fewer tadpoles. These normally play an important role in controlling the growth of algae and also forage on detritus that accumulates as sediment on the bottom. A reduction in the number of tadpoles may lead to an overgrowth of algae, resulting in depletion of oxygen in the water when the algae later die and decompose. Aquatic invertebrates and fish might then die and there would be unpredictable ecological consequences.[142]

A global strategy to stem the crisis was released in 2005 in the form of the Amphibian Conservation Action Plan. Developed by over eighty leading experts in the field, this call to action details what would be required to curtail amphibian declines and extinctions over the following five years and how much this would cost. The Amphibian Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union (IUCN) is spearheading efforts to implement a comprehensive global strategy for amphibian conservation.[143] Amphibian Ark is an organization that was formed to implement the ex-situ conservation recommendations of this plan, and they have been working with zoos and aquaria around the world, encouraging them to create assurance colonies of threatened amphibians.[143] One such project is the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project that built on existing conservation efforts in Panama to create a country-wide response to the threat of chytridiomycosis.[144]

See also[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

References[Επεξεργασία | επεξεργασία κώδικα]

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 Κατηγορία:Animal classes Blackburn, D. C.; Wake, D. B. (2011). «Class Amphibia Gray, 1825. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness». Zootaxa 3148: 39–55. http://mapress.com/zootaxa/2011/f/zt03148p055.pdf.

- ↑ Skeat, Walter W. (1897). A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Clarendon Press. σελ. 39.

- ↑ Baird, Donald (1965). «Paleozoic lepospondyl amphibians». Integrative and Comparative Biology 5 (2): 287–294. doi:.

- ↑ Hickman, Cleveland P. JR (2011). Αποστολοπούλου, Μαρία, επιμ. Ζωολογία: Ολοκληρωμένες Αρχές. II (2η ελληνική έκδοση). Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Utopia. σελ. 768. ISBN 9789609928038.

- ↑ Frost, Darrel (2013). «American Museum of Natural History: Amphibian Species of the World 5.6, an Online Reference». The American Museum of Natural History. Ανακτήθηκε στις 24 Οκτωβρίου 2013.

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 Crump, Martha L. (2009). «Amphibian diversity and life history». Amphibian Ecology and Conservation. A Handbook of Techniques: 3–20. http://fds.oup.com/www.oup.com/pdf/13/9780199541188_chapter1.pdf.

- ↑ Speer, B. W.; Waggoner, Ben (1995). «Amphibia: Systematics». University of California Museum of Paleontology. Ανακτήθηκε στις 13 Δεκεμβρίου 2012.

- ↑ 8,0 8,1 8,2 Stebbins & Cohen 1995, σελ. 3.

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 Anderson, J.; Reisz, R.; Scott, D.; Fröbisch, N.; Sumida, S. (2008). «A stem batrachian from the Early Permian of Texas and the origin of frogs and salamanders». Nature 453 (7194): 515–518. doi:. PMID 18497824.

- ↑ Roček, Z. (2000). «14. Mesozoic Amphibians». Στο: Heatwole, H.· Carroll, R. L. Amphibian Biology: Paleontology: The Evolutionary History of Amphibians (PDF). 4. Surrey Beatty & Sons. σελίδες 1295–1331. ISBN 978-0-949324-87-0.

- ↑ Jenkins, Farish A. Jr.; Walsh, Denis M.; Carroll, Robert L. (2007). «Anatomy of Eocaecilia micropodia, a limbed caecilian of the Early Jurassic». Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 158 (6): 285–365. doi:.

- ↑ Gaoa, Ke-Qin; Shubin, Neil H. (2012). «Late Jurassic salamandroid from western Liaoning, China». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (15): 5767–5772. doi:. PMID 22411790. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..109.5767G.

- ↑ Cannatella, David (2008). «Salientia». Tree of Life Web Project. Ανακτήθηκε στις 31 Αυγούστου 2012.

- ↑ 14,0 14,1 14,2 «Evolution of amphibians». University of Waikato: Plant and animal evolution. Ανακτήθηκε στις 30 Σεπτεμβρίου 2012.

- ↑ 15,0 15,1 15,2 Carroll, Robert L.· Hallam, Anthony (Ed.) (1977). Patterns of Evolution, as Illustrated by the Fossil Record. Elsevier. σελίδες 405–420. ISBN 978-0-444-41142-6.

- ↑ 16,0 16,1 Clack, Jennifer A. (2006). «Ichthyostega». Tree of Life Web Project. Ανακτήθηκε στις 29 Σεπτεμβρίου 2012.

- ↑ Lombard, R. E.; Bolt, J. R. (1979). «Evolution of the tetrapod ear: an analysis and reinterpretation». Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 11 (1): 19–76. doi:.

- ↑ 18,0 18,1 18,2 Spoczynska, J. O. I. (1971). Fossils: A Study in Evolution. Frederick Muller Ltd. σελίδες 120–125. ISBN 978-0-584-10093-8.

- ↑ Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. and Ferry, P.A. (2010). «Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land» (PDF). Biology Letters 6 (4): 544–547. doi:. PMID 20106856. PMC 2936204. http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/6/4/544.full.pdf+html.