Καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου: Διαφορά μεταξύ των αναθεωρήσεων

μΧωρίς σύνοψη επεξεργασίας |

μΧωρίς σύνοψη επεξεργασίας |

||

| Γραμμή 220: | Γραμμή 220: | ||

Οι γενετικές μεταλλάξεις εμφανίζονται σε ορώδης καρκίνωμα είναι χρωμοσωμική αστάθεια και μεταλλάξεις στο ΤΡ53, μια σημαντική ογκοκατασταλτικό γονίδιο. [3] |

Οι γενετικές μεταλλάξεις εμφανίζονται σε ορώδης καρκίνωμα είναι χρωμοσωμική αστάθεια και μεταλλάξεις στο ΤΡ53, μια σημαντική ογκοκατασταλτικό γονίδιο. [3] |

||

===== |

=====Σαφές Καρκίνωμα===== |

||

{{see also|Uterine clear-cell carcinoma}}Σαφή καρκίνωμα είναι μια ενδομητρίου όγκου τύπου ΙΙ που αντιστοιχεί σε λιγότερο από το 5% των διαγνωσμένων καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. Σαν ορώδης καρκίνωμα, είναι συνήθως επιθετική και φέρει μια φτωχή πρόγνωση. Ιστολογικά, χαρακτηρίζεται από τα χαρακτηριστικά που είναι κοινά σε όλα τα [κύτταρο | διαυγοκυτταρικό] s: ο επώνυμος διαφανές κυτταρόπλασμα όταν [λεκέ | H & E λεκέ], εκδ και ορατές, διακριτές κυτταρικές μεμβράνες [5] σύστημα σηματοδότησης Το κύτταρο p53 δεν δραστηριοποιείται. ενδομητρίου σαφές καρκίνωμα. [6] Αυτή η μορφή καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου είναι πιο συχνή στις μετεμμηνοπαυσιακές γυναίκες. [7] |

|||

===== |

|||

{{see also|Uterine clear-cell carcinoma}} |

|||

Clear cell carcinoma is a Type II endometrial tumor that makes up less than 5% of diagnosed endometrial cancer. Like serous cell carcinoma, it is usually aggressive and carries a poor prognosis. Histologically, it is characterized by the features common to all [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clear cell|clear cell]]s: the eponymous clear cytoplasm when [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H&E stain|H&E stain]]ed and visible, distinct cell membranes.<ref name="Hoffman">{{cite book |editor-last1=Hoffman |editor-first1=BL |editor-last2=Schorge |editor-first2=JO |editor-last3=Schaffer |editor-first3=JI |editor-last4=Halvorson |editor-first4=LM |editor-last5=Bradshaw |editor-first5=KD |editor-last6=Cunningham |editor-first6=FG |year=2012 |chapter=Endometrial Cancer |url=http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=56712550 |title=Williams Gynecology |edition=2nd |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]] |isbn=978-0-07-171672-7}}</ref> The p53 cell signaling system is not active in endometrial clear cell carcinoma.<ref name="bmj">{{cite journal |last1=Saso |first1=S |last2=Chatterjee |first2=J |last3=Georgiou |first3=E |last4=Ditri |first4=AM |last5=Smith |first5=JR |last6=Ghaem-Maghami |first6=S |year=2011 |title=Endometrial cancer |journal=BMJ |volume=343 |issue= |pages=d3954–d3954 |doi=10.1136/bmj.d3954 |pmid=21734165}}</ref> This form of endometrial cancer is more common in postmenopausal women.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn32">{{cite book |last1=Soliman |first1=PT |last2=Lu |first2=KH |year=2013 |chapter=Neoplastic Diseases of the Uterus |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> |

|||

===== |

|||

========== |

|||

=====Mucinous carcinoma===== |

=====Mucinous carcinoma===== |

||

Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα είναι μια σπάνια μορφή καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, που αποτελούν λιγότερο από το 1-2% του συνόλου των διαγνωστεί με καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου είναι πιο συχνά στο στάδιο Ι και Α τάξη, δίνοντάς τους μια καλή πρόγνωση. Που κατά κανόνα έχουν καλά διαφοροποιημένα κιονοειδή κύτταρα οργανώνονται σε αδένες με τη χαρακτηριστική βλεννίνη στο κυτταρόπλασμα. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα πρέπει να διαφοροποιούνται από καρκίνο του τραχήλου αδενοκαρκίνωμα. [1]<br> |

Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα είναι μια σπάνια μορφή καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, που αποτελούν λιγότερο από το 1-2% του συνόλου των διαγνωστεί με καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου είναι πιο συχνά στο στάδιο Ι και Α τάξη, δίνοντάς τους μια καλή πρόγνωση. Που κατά κανόνα έχουν καλά διαφοροποιημένα κιονοειδή κύτταρα οργανώνονται σε αδένες με τη χαρακτηριστική βλεννίνη στο κυτταρόπλασμα. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα πρέπει να διαφοροποιούνται από καρκίνο του τραχήλου αδενοκαρκίνωμα. [1]<br> |

||

=====Mucinous carcinoma===== |

|||

[καρκίνωμα | βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα] s είναι μια σπάνια μορφή καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, που αποτελούν λιγότερο από το 1-2% του συνόλου των διαγνωστεί με καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου είναι πιο συχνά στο στάδιο Ι και Α τάξη, δίνοντάς τους μια καλή πρόγνωση. Που κατά κανόνα έχουν καλά διαχωριζόμενες κιονοειδή κύτταρα οργανώνονται σε αδένες με στο κυτταρόπλασμα το χαρακτηριστικό []. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα πρέπει να διαφοροποιηθεί από [αδενοκαρκίνωμα | τραχήλου αδενοκαρκίνωμα]. [5] |

[καρκίνωμα | βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα] s είναι μια σπάνια μορφή καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, που αποτελούν λιγότερο από το 1-2% του συνόλου των διαγνωστεί με καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου είναι πιο συχνά στο στάδιο Ι και Α τάξη, δίνοντάς τους μια καλή πρόγνωση. Που κατά κανόνα έχουν καλά διαχωριζόμενες κιονοειδή κύτταρα οργανώνονται σε αδένες με στο κυτταρόπλασμα το χαρακτηριστικό []. Βλεννώδες καρκίνωμα πρέπει να διαφοροποιηθεί από [αδενοκαρκίνωμα | τραχήλου αδενοκαρκίνωμα]. [5] |

||

===== Μικτό ή αδιαφοροποίητο καρκίνωμα ===== |

|||

=====Mixed or undifferentiated carcinoma===== |

|||

Μικτά καρκινώματα είναι εκείνα που έχουν τόσο τύπου Ι και τα κύτταρα τύπου II, με μία σε ποσοστό τουλάχιστον 10% του όγκου [1] Αυτά περιλαμβάνουν τον κακοήθη [Müllerian όγκος | αναμίχθηκε Müllerian όγκος]., Που προέρχεται από ενδομήτρια επιθήλιο και έχει φτωχή πρόγνωση. [8] Μικτό Müllerian όγκοι τείνουν να συμβαίνουν σε γυναίκες μετά την εμμηνόπαυση. [3] |

|||

Μη διαφοροποιημένα καρκινώματα του ενδομητρίου αποτελούν λιγότερο από το 1-2% των διαγνωσμένων καρκίνων του ενδομητρίου. Έχουν μια χειρότερη πρόγνωση από όγκους βαθμίδας III. Ιστολογικά, οι όγκοι αυτοί παρουσιάζουν φύλλα πανομοιότυπα επιθηλιακών κυττάρων χωρίς αναγνωρίσιμο πρότυπο. [5] |

|||

Mixed carcinomas are those that have both Type I and Type II cells, with one making up at least 10% of the tumor.<ref name="Hoffman">{{cite book |editor-last1=Hoffman |editor-first1=BL |editor-last2=Schorge |editor-first2=JO |editor-last3=Schaffer |editor-first3=JI |editor-last4=Halvorson |editor-first4=LM |editor-last5=Bradshaw |editor-first5=KD |editor-last6=Cunningham |editor-first6=FG |year=2012 |chapter=Endometrial Cancer |url=http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=56712550 |title=Williams Gynecology |edition=2nd |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]] |isbn=978-0-07-171672-7}}</ref> These include the malignant [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mixed Müllerian tumor|mixed Müllerian tumor]], which derives from endometrial epithelium and has a poor prognosis.<ref name="Cochrane 1011">{{cite cochrane |last1=Johnson |first1=N |last2=Bryant |first2=A |last3=Miles |first3=T |last4=Hogberg |first4=T |last5=Cornes |first5=P |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2011 |title=Adjuvant chemotherapy for endometrial cancer after hysterectomy |review=CD003175 |version=2 |pmid=21975736}}</ref> Mixed Müllerian tumors tend to occur in postmenopausal women.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn32">{{cite book |last1=Soliman |first1=PT |last2=Lu |first2=KH |year=2013 |chapter=Neoplastic Diseases of the Uterus |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> |

|||

''' Άλλα καρκινώματα''' |

|||

Undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas make up less than 1–2% of diagnosed endometrial cancers. They have a worse prognosis than grade III tumors. Histologically, these tumors show sheets of identical epithelial cells with no identifiable pattern.<ref name="Hoffman" /> |

|||

Μη μεταστατικό [καρκίνωμα | πλακώδες καρκίνωμα] και [καρκίνωμα | μεταβατικό καρκίνωμα] είναι πολύ σπάνια στο ενδομήτριο. Πλακώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου έχει μία κακή πρόγνωση. [1] Έχει αναφερθεί λιγότερες από 100 φορές στην ιατρική βιβλιογραφία από τον χαρακτηρισμό του το 1892. Για πρωτογενή πλακώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου (PSCCE) που πρόκειται να διαγνωστεί, πρέπει να υπάρχει καμία άλλη πρωτοπαθή καρκίνο στο ενδομήτριο ή του τραχήλου της μήτρας και δεν πρέπει να συνδεθεί με το τραχηλικό επιθήλιο. Λόγω της σπανιότητας του καρκίνου αυτού, δεν υπάρχουν οδηγίες για το πώς θα πρέπει να αντιμετωπιστεί, ούτε τυπική θεραπεία. Οι κοινές γενετικές αιτίες παραμένουν χωρίς χαρακτηρισμό [9] Δημοτικό μεταβατικό καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου είναι ακόμα πιο σπάνιο.? 16 περιπτώσεις είχαν αναφερθεί Πρότυπο: Όπως του. Παθοφυσιολογία και τις θεραπείες της δεν έχουν χαρακτηριστεί. [10] Ιστολογικά, TCCE μοιάζει με καρκίνωμα ενδομητριοειδούς και είναι διαφορετικό από άλλα καρκινώματα εκ μεταβατικού επιθηλίου. [11] |

|||

=====Other carcinomas===== |

|||

====Σάρκωμα==== |

|||

Non-metastatic [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squamous cell carcinoma|squamous cell carcinoma]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transitional cell carcinoma|transitional cell carcinoma]] are very rare in the endometrium. Squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium has a poor prognosis.<ref name="Hoffman" /> It has been reported fewer than 100 times in the medical literature since its characterization in 1892. For primary squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium (PSCCE) to be diagnosed, there must be no other primary cancer in the endometrium or cervix and it must not be connected to the cervical epithelium. Because of the rarity of this cancer, there are no guidelines for how it should be treated, nor any typical treatment. The common genetic causes remain uncharacterized.<ref name="Goodrich">{{cite journal |last1=Goodrich |first1 = S |last2 = Kebria-Moslemi |first2 = M |last3 = Broshears |first3 = J |last4 = Sutton |first4 = GP |last5 = Rose |first5 = P |title=Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium: two cases and a review of the literature |journal=Diagnostic Cytopathology |volume=41 |issue=9 |pages=817–20 |date=September 2013 |pmid=22241749 |doi=10.1002/dc.22814 |url=}}</ref> Primary transitional cell carcinomas of the endometrium are even more rare; 16 cases had been reported {{as of|2008|lc=on}}. Its pathophysiology and treatments have not been characterized.<ref name="Marino">{{cite journal |last1 =Mariño-Enríquez |first1 = A |last2 = González-Rocha |first2 = T |last3 = Burgos |first3 = E |others = et al. |title=Transitional cell carcinoma of the endometrium and endometrial carcinoma with transitional cell differentiation: a clinicopathologic study of 5 cases and review of the literature |journal=Human Pathology |volume=39 |issue=11 |pages=1606–13 |date=November 2008 |pmid=18620731 |doi=10.1016/j.humpath.2008.03.005 |url=}}</ref> Histologically, TCCE resembles endometrioid carcinoma and is distinct from other transitional cell carcinomas.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Ahluwalia |first1 = M |last2 = Light |first2 = AM |last3 = Surampudi |first3 = K |last4 = Finn |first4 = CB |title=Transitional cell carcinoma of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literature |journal= International Journal of Gynecological Pathology |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=378–82 |date=October 2006 |pmid=16990716 |doi=10.1097/01.pgp.0000215296.53361.4b |url=}}</ref> |

|||

====Sarcoma==== |

|||

{{main|Endometrial stromal sarcoma}} |

{{main|Endometrial stromal sarcoma}} |

||

[[File:Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma very high mag.jpg|thumb|alt=Image of the histology of an endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma|Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma – very high magnification – H&E stain|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Endometrioid_endometrial_adenocarcinoma_very_high_mag.jpg]] |

[[File:Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma very high mag.jpg|thumb|alt=Image of the histology of an endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma|Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma – very high magnification – H&E stain|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Endometrioid_endometrial_adenocarcinoma_very_high_mag.jpg]] |

||

In contrast to endometrial carcinomas, the uncommon endometrial stromal [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarcomas|sarcomas]] are cancers that originate in the non-glandular [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connective tissue|connective tissue]] of the endometrium. They are generally non-aggressive and, if they recur, can take decades. Metastases to the lungs and pelvic or peritoneal cavities are the most frequent.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn32" /> They typically have estrogen and/or progesterone receptors.<ref name="Sylvestre">{{cite journal |last1 = Sylvestre |first1 = VT |last2 = Dunton |first2 = CJ |title=Treatment of recurrent endometrial stromal sarcoma with letrozole: a case report and literature review |journal=Hormones and Cancer |volume=1 |issue=2 |pages=112–5 |date=April 2010 |pmid=21761354 |doi=10.1007/s12672-010-0007-9 |url=}}</ref> The prognosis for low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma is good, with 60–90% 5-year survival. [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-grade undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma|High-grade undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma]] (HGUS) has a worse prognosis, with high rates of recurrence and 25% 5-year survival.<ref name="Hensley">{{cite journal |author=Hensley ML |title=Uterine sarcomas: histology and its implications on therapy |journal=American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book |volume= |issue= |pages=356–61 |year=2012 |pmid=24451763 |doi=10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.356 |url=}}</ref> HGUS prognosis is dictated by whether or not the cancer has invaded the arteries and veins. Without vascular invasion, the 5-year survival is 83%; it drops to 17% when vascular invasion is observed. Stage I ESS has the best prognosis, with 5-year survival of 98% and 10-year survival of 89%. ESS makes up 0.2% of uterine cancers.<ref name="D">{{cite journal |last1 =D'Angelo |first1 = E |last2 = Prat |first2 = J |title=Uterine sarcomas: a review |journal=Gynecologic Oncology |volume=116 |issue=1 |pages=131–9 |date=January 2010 |pmid=19853898 |doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.023 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

===== |

|||

=====<nowiki/>===== |

=====<nowiki/>===== |

||

===== Σε αντίθεση με την ενδομήτρια καρκινώματα, τα ασυνήθιστο ενδομητρίου στρωματικά σαρκώματα είναι καρκίνους που προέρχονται από το μη-αδενικού συνδετικού ιστού του ενδομητρίου. Είναι γενικά μη-επιθετική και, εάν επαναληφθεί, μπορεί να πάρει δεκαετίες. Οι μεταστάσεις στους πνεύμονες και της πυέλου ή περιτοναϊκή κοιλότητα είναι η πιο συχνή. [1] Έχουν συνήθως οιστρογόνων ή / και προγεστερόνης υποδοχέων. [32] Η πρόγνωση για χαμηλής ποιότητας του ενδομητρίου στρωματικά σάρκωμα είναι καλή, με 60-90% 5-ετή επιβίωση. Υψηλής ποιότητας αδιαφοροποίητο σάρκωμα του ενδομητρίου (HGUS) έχει χειρότερη πρόγνωση, με υψηλά ποσοστά υποτροπής και 25% 5-ετή επιβίωση. [33] HGUS πρόγνωση υπαγορεύεται από το αν ή όχι ο καρκίνος έχει διηθήσει τις αρτηρίες και τις φλέβες. Χωρίς αγγειακή εισβολή, η επιβίωση 5 ετών είναι 83%? πέφτει στο 17%, όταν παρατηρείται αγγειακή εισβολή. Στάδιο Ι ΕΣΣ έχει την καλύτερη πρόγνωση, με 5-ετή επιβίωση του 98% και 10-ετής επιβίωση του 89%. ΕΣΣ αποτελεί 0,2% των καρκίνων της μήτρας. [34] ===== |

|||

===Metastasis=== |

|||

Endometrial cancer frequently metastasizes to the ovaries and Fallopian tubes<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn33">{{cite book |last1=Coleman |first1=RL |last2=Ramirez |first2=PT |last3=Gershenson |first3=DM |year=2013 |chapter=Neoplastic Diseases of the Ovary |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> when the cancer is located in the upper part of the uterus, and the cervix when the cancer is in the lower part of the uterus. The cancer usually first spreads into the myometrium and the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serosa|serosa]], then into other reproductive and pelvic structures. When the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lymphatic system|lymphatic system]] is involved, the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelvic lymph nodes|pelvic]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Para-aortic lymph nodes|para-aortic nodes]] are usually first to become involved, but in no specific pattern, unlike cervical cancer. More distant metastases are spread by the blood and often occur in the lungs, as well as the liver, brain, and bone.<ref name="Hoffman2">{{cite book |editor-last1=Hoffman |editor-first1=BL |editor-last2=Schorge |editor-first2=JO |editor-last3=Schaffer |editor-first3=JI |editor-last4=Halvorson |editor-first4=LM |editor-last5=Bradshaw |editor-first5=KD |editor-last6=Cunningham |editor-first6=FG |year=2012 |chapter=Endometrial Cancer |url=http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=56712550 |title=Williams Gynecology |edition=2nd |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]] |isbn=978-0-07-171672-7}}</ref> Endometrial cancer metastasizes to the lungs 20–25% of the time, more than any other gynecologic cancer.<ref name="Kurra" /> |

|||

===Histopathology=== |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

<!-- Essential parameters --> |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| width = 180 |

|||

<!-- Image 1 --> |

|||

|image1 = Adenocarcinoma of the Endometrium.jpg |

|||

|caption1 = A stage I, grade I section of an endometrial cancer after hysterectomy |

|||

|alt1 = A section of a stage I, grade I endometrial cancer |

|||

<!-- Image 2 --> |

|||

|image2 = Endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus FIGO grade III.jpg |

|||

|caption2 = A stage III endometrioid adenocarcinoma that has invaded the myometrium |

|||

|alt2=A stage III endometrial cancer that has invaded the myometrium of the uterus |

|||

<!-- Image 3 --> |

|||

|image3 = Metastatic endometrial carcinoma (3944215367).jpg |

|||

|caption3 = Metastatic endometrial cancer seen in a removed lung |

|||

|alt3=A gross pathology image of endometrial cancer metastasized to the lung. |

|||

}}There is a three-tiered system for histologically classifying endometrial cancers, ranging from cancers with well-differentiated cells (grade I), to very poorly-differentiated cells (grade III).<ref name="Cochrane0812">{{cite cochrane |last1=Vale |first1=CL |last2=Tierney |first2=J |last3=Bull |first3=SJ |last4=Symonds |first4=PR |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2012 |title=Chemotherapy for advanced, recurrent or metastatic endometrial carcinoma |review=CD003915 |version=4 |pmid=22895938}}</ref> Grade I cancers are the least aggressive and have the best prognosis, while grade III tumors are the most aggressive and likely to recur. Grade II cancers are intermediate between grades I and III in terms of cell differentiation and aggressiveness of disease.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> |

|||

The histopathology of endometrial cancers is highly diverse. The most common finding is a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma,<ref name="Cochrane 10112">{{cite cochrane |last1=Johnson |first1=N |last2=Bryant |first2=A |last3=Miles |first3=T |last4=Hogberg |first4=T |last5=Cornes |first5=P |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2011 |title=Adjuvant chemotherapy for endometrial cancer after hysterectomy |review=CD003175 |version=2 |pmid=21975736}}</ref> which is composed of numerous, small, crowded glands with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and stratification. This often appears on a background of endometrial hyperplasia. Frank adenocarcinoma may be distinguished from atypical hyperplasia by the finding of clear stromal invasion, or "back-to-back" glands which represent nondestructive replacement of the endometrial stroma by the cancer. With progression of the disease, the myometrium is infiltrated.<ref name="Weidner's">{{cite book |editor-last1=Weidner |editor-first1=N |editor-last2=Coté |editor-first2=R |editor-last3=Suster |editor-first3=S |editor-last4=Weiss |editor-first4=L|displayeditors=4 |year=2002 |title=Modern Surgical Pathology (2 Volume Set) |publisher=[[WB Saunders]] |isbn=978-0-7216-7253-3}}</ref> |

|||

===Staging=== |

|||

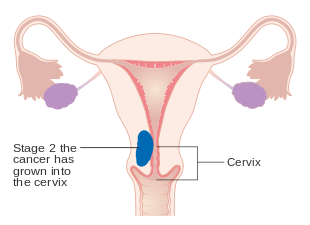

Endometrial carcinoma is surgically staged using the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics|FIGO]] [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancer staging|cancer staging]] system. The 2009 FIGO staging system is as follows:<ref>{{cite web |title=Stage Information for Endometrial Cancer |url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/endometrial/HealthProfessional/page3 |publisher=[[National Cancer Institute]] |accessdate=23 April 2014}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

!Stage |

|||

!Description |

|||

|- |

|||

|IA |

|||

|Tumor is confined to the uterus with less than half myometrial invasion |

|||

|- |

|||

|IB |

|||

|Tumor is confined to the uterus with more than half myometrial invasion |

|||

|- |

|||

|II |

|||

|Tumor involves the uterus and the cervical [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stroma (animal tissue)|stroma]] |

|||

|- |

|||

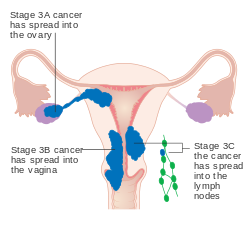

|IIIA |

|||

|Tumor invades [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serosa|serosa]] or [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adnexa of uterus|adnexa]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|IIIB |

|||

|Vaginal and/or [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parametrium|parametrial]] involvement |

|||

|- |

|||

|IIIC1 |

|||

|Pelvic lymph node involvement |

|||

|- |

|||

|IIIC2 |

|||

|Para-aortic lymph node involvement, with or without pelvic node involvement |

|||

|- |

|||

|IVA |

|||

|Tumor invades bladder mucosa and/or bowel mucosa |

|||

|- |

|||

|IVB |

|||

|Distant metastases including abdominal metastases and/or [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inguinal lymph node|inguinal lymph node]]s |

|||

|}Myometrial invasion and involvement of the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes are the most commonly seen patterns of spread.<ref name="Cochrane0412">{{cite cochrane |last1=Kong |first1=A |last2=Johnson |first2=N |last3=Kitchener |first3=HC |last4=Lawrie |first4=TA |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2012 |title=Adjuvant radiotherapy for stage I endometrial cancer |review=CD003916 |version=4 |pmid=22513918}}</ref> A Stage 0 is sometimes included, in this case it is referred to as "[[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carcinoma in situ|carcinoma in situ]]".<ref name="NCIBooklet">{{cite web|title=What You Need To Know: Endometrial Cancer|url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/uterus|website=NCI|publisher=National Cancer Institute|accessdate=6 August 2014}}</ref> In 26% of presumably early-stage cancers, intraoperative staging revealed pelvic and distant metastases, making comprehensive surgical staging necessary.<ref name="Burke1" /><gallery mode="packed" heights="150px"> |

|||

File:Diagram showing stage 1A and 1B cancer of the womb CRUK 196.svg|Stage IA and IB endometrial cancer|alt=A diagram of stage IA and IB endometrial cancer |

|||

File:Diagram showing stage 2 cancer of the womb CRUK 206.svg|Stage II endometrial cancer|alt=A diagram of stage II endometrial cancer |

|||

File:Diagram showing stage 3A to 3C cancer of the womb CRUK 224.svg|Stage III endometrial cancer|alt=A diagram of stage III endometrial cancer |

|||

File:Diagram showing stage 4A and 4B cancer of the womb CRUK 234.svg|Stage IV endometrial cancer|alt=A diagram of stage IV endometrial cancer |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Management== |

|||

===Surgery=== |

|||

[[File:Diagram showing keyhole hysterectomy CRUK 164.svg|thumb|A keyhole hysterectomy, one possible surgery to treat endometrial cancer|alt=|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diagram_showing_keyhole_hysterectomy_CRUK_164.svg]]The primary treatment for endometrial cancer is surgery; 90% of women with endometrial cancer are treated with some form of surgery.<ref name="Cochrane08122">{{cite cochrane |last1 = Vale|first1 = CL|last2 = Tierney|first2 = J|last3 = Bull|first3 = SJ|last4 = Symonds|first4 = PR|group = Gynaecological Cancer|year = 2012|title = Chemotherapy for advanced, recurrent or metastatic endometrial carcinoma|review = CD003915|version = 4|pmid = 22895938}} |

|||

</ref> Surgical treatment typically consists of [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hysterectomy|hysterectomy]] including a bilateral [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salpingo-oophorectomy|salpingo-oophorectomy]], which is the removal of the uterus, and both ovaries and Fallopian tubes. [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lymphadenectomy|Lymphadenectomy]], or removal of pelvic and para-aortic [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lymph node|lymph node]]s, is performed for tumors of histologic grade II or above.<ref name="Cochrane0514">{{cite cochrane |last1=Galaal |first1=K |last2=Al Moundhri |first2=M |last3=Bryant |first3=A |last4=Lopes |first4=AD |last5=Lawrie |first5=TA |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2014 |title=Adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced endometrial cancer |review=CD010681 |version=2 |pmid=24832785}}</ref> Lymphadenectomy is routinely performed for all stages of endometrial cancer in the United States, but in the United Kingdom, the lymph nodes are typically only removed with disease of stage II or greater.<ref name="bmj2">{{cite journal |last1=Saso |first1=S |last2=Chatterjee |first2=J |last3=Georgiou |first3=E |last4=Ditri |first4=AM |last5=Smith |first5=JR |last6=Ghaem-Maghami |first6=S |year=2011 |title=Endometrial cancer |journal=BMJ |volume=343 |issue= |pages=d3954–d3954 |doi=10.1136/bmj.d3954 |pmid=21734165}}</ref> The topic of lymphadenectomy and what survival benefit it offers in stage I disease is still being debated.<ref name="Colombo" /> In stage III and IV cancers, [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytoreductive surgery|cytoreductive surgery]] is the norm,<ref name="Cochrane0514" /> and a biopsy of the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater omentum|omentum]] may also be included.<ref name="Cochrane0912" /> In stage IV disease, where there are distant metastases, surgery can be used as part of palliative therapy.<ref name="Colombo" /> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laparotomy|Laparotomy]], an open-abdomen procedure, is the traditional surgical procedure; however, [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laparoscopy|laparoscopy]] (keyhole surgery) is associated with lower operative morbidity. The two procedures have no difference in overall survival.<ref name="Cochrane0912">{{cite cochrane |last1=Galaal |first1=K |last2=Bryant |first2=A |last3=Fisher |first3=AD |last4=Al-Khaduri |first4=M |last5=Kew |first5=F |last6=Lopes |first6=AD |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2012 |title=Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer |review=CD006655 |version=2 |pmid=22972096}}</ref> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdominal hysterectomy|Removal of the uterus via the abdomen]] is recommended over [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaginal hysterectomy|removal of the uterus via the vagina]] because it gives the opportunity to examine and obtain [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peritoneal washing|washings]] of the abdominal cavity to detect any further evidence of cancer. Staging of the cancer is done during the surgery.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> |

|||

The few contraindications to surgery include inoperable tumor, massive obesity, a particularly high-risk operation, or a desire to preserve fertility.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> These contraindications happen in about 5–10% of cases.<ref name="Colombo" /> Women who wish to preserve their fertility and have low-grade stage I cancer can be treated with progestins, with or without concurrent tamoxifen therapy. This therapy can be continued until the cancer does not respond to treatment or until childbearing is done.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uterine perforation|Uterine perforation]] may occur during a D&C or an endometrial biopsy.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn35">{{cite book |last1=McGee |first1=J |last2=Covens |first2=A |year=2013 |chapter=Gestational Trophoblastic Disease |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> Side effects of surgery to remove endometrial cancer can specifically include sexual dysfunction, temporary incontinence, and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lymphedema|lymphedema]], along with more common side effects of any surgery, including [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constipation|constipation]].<ref name="NCIBooklet" /> |

|||

===Add-on therapy=== |

|||

There are a number of possible additional therapies. Surgery can be followed by [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radiation therapy|radiation therapy]] and/or [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemotherapy|chemotherapy]] in cases of high-risk or high-grade cancers. This is called [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adjuvant therapy|adjuvant therapy]].<ref name="Cochrane0514" /> |

|||

====Chemotherapy==== |

|||

[[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adjuvant chemotherapy|Adjuvant chemotherapy]] is a recent innovation, consisting of some combination of [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paclitaxel|paclitaxel]] (or other [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxane|taxane]]s like [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Docetaxel|docetaxel]]), [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doxorubicin|doxorubicin]] (and other [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthracyclines|anthracyclines]]), and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platins|platins]] (particularly [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cisplatin|cisplatin]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carboplatin|carboplatin]]). Adjuvant chemotherapy has been found to increase survival in stage III and IV cancer more than [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adjuvant radiotherapy|added radiotherapy]].<ref name="Cochrane0514" /><ref name="Colombo" /><ref name="Cochrane0812" /><ref name="ComprehensiveGyn27">{{cite book |last1=Smith |first1=JA |last2=Jhingran |first2=A |year=2013 |chapter=Principles of Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in Gynecologic Cancer |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> Mutations in mismatch repair genes, like those found in Lynch syndrome, can lead to resistance against platins, meaning that chemotherapy with platins is ineffective in people with these mutations.<ref name="Guillotin">{{cite journal |last1=Guillotin |first1=D |last2=Martin |first2=SA |year=2014 |title=Exploiting DNA mismatch repair deficiency as a therapeutic strategy |journal=Experimental Cell Research |volume= |issue= |pages= |doi= 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.004 |pmid=25017099}}</ref> Side effects of chemotherapy are common. These include [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alopecia|hair loss]], [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutropenia|low neutrophil levels]] in the blood, and gastrointestinal problems.<ref name="Cochrane0514" /> |

|||

In cases where surgery is not indicated, [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palliative chemotherapy|palliative chemotherapy]] is an option; higher-dose chemotherapy is associated with longer survival.<ref name="Cochrane0514" /><ref name="Cochrane0812" /><ref name="ComprehensiveGyn27" /> Palliative chemotherapy, particularly using [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capecitabine|capecitabine]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gemcitabine|gemcitabine]], is also often used to treat recurrent endometrial cancer.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn27" /> |

|||

====Radiotherapy==== |

|||

Adjuvant radiotherapy is commonly used in early-stage (stage I or II) endometrial cancer. It can be delivered through vaginal brachytherapy (VBT), which is becoming the preferred route due to its reduced toxicity, or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT). Brachytherapy involves placing a radiation source in the organ affected; in the case of endometrial cancer a radiation source is placed directly in the vagina. External beam radiotherapy involves a beam of radiation aimed at the affected area from outside the body. VBT is used to treat any remaining cancer solely in the vagina, whereas EBRT can be used to treat remaining cancer elsewhere in the pelvis following surgery. However, the benefits of adjuvant radiotherapy are controversial. Though EBRT significantly reduces the rate of relapse in the pelvis, overall survival and metastasis rates are not improved.<ref name="Cochrane0412" /> VBT provides a better quality of life than EBRT.<ref name="Colombo" /> |

|||

Radiotherapy can also be used before surgery in certain cases. When pre-operative imaging or clinical evaluation shows tumor invading the cervix, radiation can be given before a [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radical hysterectomy|total hysterectomy]] is performed.<ref name="CurrentSurgery">{{cite book |last1=Reynolds |first1=RK |last2=Loar III |first2=PV |year=2010 |chapter=Gynecology |editor-last=Doherty |editor-first=GM |title=Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery |edition=13th |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]] |isbn=978-0-07-163515-8}}</ref> Brachytherapy and EBRT can also be used, singly or in combination, when there is a contraindication for hysterectomy.<ref name="Colombo" /> Both delivery methods of radiotherapy are associated with side effects, particularly in the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human gastrointestinal tract|gastrointestinal tract]].<ref name="Cochrane0412" /> |

|||

====Hormonal therapy==== |

|||

Hormonal therapy is only beneficial in certain types of endometrial cancer. It was once thought to be beneficial in most cases.<ref name="Cochrane0412" /><ref name="Cochrane0514" /> If a tumor is well-differentiated and known to have progesterone and estrogen receptors, progestins may be used in treatment.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn27" /> About 25% of metastatic endometrioid cancers show a response to progestins. Also, endometrial stromal sarcomas can be treated with hormonal agents, including tamoxifen, [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate|17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate]], [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letrozole|letrozole]], [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megestrol acetate|megestrol acetate]], and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medroxyprogesterone|medroxyprogesterone]].<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn322" /> This treatment is effective in endometrial stromal sarcomas because they typically have estrogen and/or progestin receptors. Preliminary research and clinical trials have shown these treatments to have a high rate of response even in metastatic disease.<ref name="Sylvestre2">{{cite journal |last1 = Sylvestre |first1 = VT |last2 = Dunton |first2 = CJ |title=Treatment of recurrent endometrial stromal sarcoma with letrozole: a case report and literature review |journal=Hormones and Cancer |volume=1 |issue=2 |pages=112–5 |date=April 2010 |pmid=21761354 |doi=10.1007/s12672-010-0007-9 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

===Monitoring=== |

|||

The tumor marker CA-125 is frequently elevated in endometrial cancer and can be used to monitor response to treatment, particularly in serous cell cancer or advanced disease.<ref name="Hoffman2" /><ref name="ComprehensiveGyn33" /> Periodic MRIs or CT scans may be recommended in advanced disease and women with a history of endometrial cancer should receive more frequent pelvic examinations for the 5 years following treatment.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> Examinations conducted every 3–4 months are recommended for the first 2 years following treatment, and every 6 months for the next 3 years.<ref name="Colombo" /> |

|||

Women with endometrial cancer should not have routine surveillance imaging to monitor the cancer unless new symptoms appear or [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tumor markers|tumor markers]] begin rising. Imaging without these indications is discouraged because it is unlikely to detect a recurrence or improve survival, and because it has its own costs and side effects.<ref name="SGOfive">{{cite web |date=31 October 2013 |title=Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question |url=http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/society-of-gynecologic-oncology/ |publisher=[[Society of Gynecologic Oncology]] |work=[[Choosing Wisely]] |accessdate=27 July 2014}}</ref> If a recurrence is suspected, PET/CT scanning is recommended.<ref name="Colombo" /> |

|||

==Prognosis== |

|||

===Survival rates=== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="float: right; margin-left:15px; text-align:center" |

|||

|+5-year relative survival rates in the US by FIGO stage:<ref>{{cite web |date=2 March 2014 |title=Survival by stage of endometrial cancer |url=http://www.cancer.org/cancer/endometrialcancer/detailedguide/endometrial-uterine-cancer-survival-rates |publisher=[[American Cancer Society]] |accessdate=10 June 2014}}</ref> |

|||

! Stage |

|||

! 5 year survival rate |

|||

|- |

|||

| I-A |

|||

| 88% |

|||

|- |

|||

| I-B |

|||

| 75% |

|||

|- |

|||

| II |

|||

| 69% |

|||

|- |

|||

| III-A |

|||

| 58% |

|||

|- |

|||

| III-B |

|||

| 50% |

|||

|- |

|||

| III-C |

|||

| 47% |

|||

|- |

|||

| IV-A |

|||

| 17% |

|||

|- |

|||

| IV-B |

|||

| 15% |

|||

|}The 5-year survival rate for endometrial adenocarcinoma following appropriate treatment is 80%.<ref name="Follow">{{cite journal |last=Nicolaije |first=KA |last2=Ezendam |first2=NP |last3=Vos |first3=MC |last4=Boll |first4=D |last5=Pijnenborg |first5=JM |last6=Kruitwagen |first6=RF |last7=Lybeert |first7=ML |last8=van de Poll-Franse |first8=LV |year=2013 |title=Follow-up practice in endometrial cancer and the association with patient and hospital characteristics: A study from the population-based PROFILES registry |journal=Gynecologic Oncology |volume=129 |issue=2 |pages=324–331 |doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.018 |pmid=23435365}}</ref> Most women, over 70%, have FIGO stage I cancer, which has the best prognosis. Stage III and IV cancer has a worse prognosis, but is relatively rare, occurring in only 13% of cases. The median survival time for stage III-IV endometrial cancer is 9–10 months.<ref name="Cochrane0214">{{cite cochrane |last1=Ang |first1=C |last2=Bryant |first2=A |last3=Barton |first3=DPJ |last4=Pomel |first4=C |last5=Naik |first5=R |group=Gynaecological Cancer |year=2014 |title=Exenterative surgery for recurrent gynaecological malignancies |review=CD010449 |version=2 |pmid=24497188}}</ref> Older age indicates a worse prognosis.<ref name="Cochrane05142">{{cite cochrane |last1 = Galaal|first1 = K|last2 = Al Moundhri|first2 = M|last3 = Bryant|first3 = A|last4 = Lopes|first4 = AD|last5 = Lawrie|first5 = TA|group = Gynaecological Cancer|year = 2014|title = Adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced endometrial cancer|review = CD010681|version = 2|pmid = 24832785}} |

|||

</ref> In the United States, white women have a higher survival rate than Black women, who tend to develop more aggressive forms of the disease.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn322">{{cite book |last1 = Soliman|first1 = PT|last2 = Lu|first2 = KH|year = 2013|chapter = Neoplastic Diseases of the Uterus|editor-last1 = Lentz|editor-first1 = GM|editor-last2 = Lobo|editor-first2 = RA|editor-last3 = Gershenson|editor-first3 = DM|editor-last4 = Katz|editor-first4 = VL|displayeditors = 4|title = Comprehensive Gynecology|edition = 6th|isbn = 978-0-323-06986-1|publisher = [[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> Tumors with high [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progesterone receptor|progesterone receptor]] expression have a good prognosis compared to tumors with low progesterone receptor expression; 93% of women with high progesterone receptor disease survived to 3 years, compared with 36% of women with low progesterone receptor disease.<ref name="NCI2014Pro">{{cite web|title=Endometrial Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)|url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/endometrial/HealthProfessional/page1/AllPages|publisher= National Cancer Institute|accessdate=3 September 2014|date=23 April 2014}}</ref> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heart disease|Heart disease]] is the most common cause of death among those who survive endometrial cancer,<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Ward|first1=KK|last2=Shah|first2=NR|last3=Saenz|first3=CC|last4=McHale|first4=MT|last5=Alvarez|first5=EA|last6=Plaxe|first6=SC|title=Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients.|journal=Gynecologic oncology|date=August 2012|volume=126|issue=2|pages=176–9|pmid=22507532|doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.013}}</ref> with other obesity related health problems also being common.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Fader|first1=AN|last2=Arriba|first2=LN|last3=Frasure|first3=HE|last4=von Gruenigen|first4=VE|title=Endometrial cancer and obesity: epidemiology, biomarkers, prevention and survivorship.|journal=Gynecologic oncology|date=July 2009|volume=114|issue=1|pages=121–7|pmid=19406460|doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.039}}</ref> |

|||

===Recurrence rates=== |

|||

Recurrence of early stage endometrial cancer ranges from 3 to 17%, depending on primary and adjuvant treatment.<ref name="Follow" /> Most recurrences (75–80%) occur outside of the pelvis, and most occur 2–3 years after treatment, 64% after 2 years and 87% after 3 years.<ref name="Kurra" /> |

|||

Higher-staged cancers are more likely to recur, as are those that have invaded the myometrium or cervix, or that have metastasized into the lymphatic system. [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papillary serous carcinoma|Papillary serous carcinoma]], [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uterine clear-cell carcinoma|clear cell carcinoma]], and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endometrioid carcinoma|endometrioid carcinoma]] are the subtypes at the highest risk of recurrence.<ref name="Cochrane0812" /> High-grade histological subtypes are also at elevated risk for recurrence.<ref name="bmj2" /> |

|||

The most common site of recurrence is in the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vagina|vagina]];<ref name="Cochrane0412" /> vaginal relapses of endometrial cancer have the best prognosis. If relapse occurs from a cancer that has not been treated with radiation, EBRT is the first-line treatment and is often successful. If a cancer treated with radiation recurs, [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelvic exenteration|pelvic exenteration]] is the only option for curative treatment. Palliative chemotherapy, cytoreductive surgery, and radiation are also performed.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> Radiation therapy (VBT and EBRT) for a local vaginal recurrence has a 50% five-year survival rate. Pelvic recurrences are treated with surgery and radiation, and abdominal recurrences are treated with radiation and, if possible, chemotherapy.<ref name="Colombo" /> Other common recurrence sites are the pelvic lymph nodes, para-aortic lymph nodes, peritoneum (28% of recurrences), and lungs, though recurrences can also occur in the brain (<1%), liver (7%), adrenal glands (1%), bones (4–7%; typically the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axial skeleton|axial skeleton]]), lymph nodes outside the abdomen (0.4–1%), spleen, and muscle/soft tissue (2–6%).<ref name="Kurra">{{cite journal |last1 = Kurra |first1 = V |last2 = Krajewski |first2 = KM |last3 = Jagannathan |first3 = J |last4 = Giardino |first4= A |last5 = Berlin |first5 = S |last6 = Ramaiya |first6 = N |title=Typical and atypical metastatic sites of recurrent endometrial carcinoma |journal=Cancer Imaging |volume=13 |issue= |pages=113–22 |year=2013 |pmid=23545091 |pmc=3613792 |doi=10.1102/1470-7330.2013.0011 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

==Epidemiology== |

|||

{{As of|2014}}, approximately 320,000 women are diagnosed with endometrial cancer worldwide each year and 76,000 die, making it the sixth most common cancer in women.<ref name="WCR2014Epi">{{cite book |author=International Agency for Research on Cancer |year=2014 |title=World Cancer Report 2014 |publisher=[[World Health Organization]] |isbn=978-92-832-0429-9 |at=Chapter 5.12}}</ref> It is more common in developed countries, where the lifetime risk of endometrial cancer in people born with uteri is 1.6%, compared to 0.6% in developing countries.<ref name="Cochrane0514" /> It [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incidence (epidemiology)|occurs]] in 12.9 out of 100,000 women annually in developed countries.<ref name="Cochrane0812" /> |

|||

In the United States, endometrial cancer is the most frequently diagnosed gynecologic cancer and, in women, the fourth most [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prevalence|common]] cancer overall,<ref name="Hoffman2" /><ref name="ComprehensiveGyn322">{{cite book |last1=Soliman |first1=PT |last2=Lu |first2=KH |year=2013 |chapter=Neoplastic Diseases of the Uterus |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> representing 6% of all cancer cases in women.<ref name="PDQ-info">{{cite web |url= http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/endometrial/HealthProfessional |title = General Information about Endometrial Cancer |date = 23 April 2014 |publisher = NIH |work = Endometrial Cancer Treatment (PDQ)}}</ref> In that country, {{As of|2014|lc=on}} it was estimated that 52,630 women were diagnosed yearly and 8,590 would die from the disease.<ref name="Burke1">{{cite journal |author=Burke WM; Orr J; Leitao M; Salom E; Gehrig P; Olawaiye AB; Brewer M; Boruta D; Villella J; Herzog T; Abu Shahin F |title=Endometrial cancer: A review and current management strategies: Part I |journal=Gynecologic Oncology |volume=134 |issue=2 |pages=385–392 |date=August 2014 |pmid=24905773 |doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.05.018 |url=}}</ref> Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, and North America have the highest rates of endometrial cancer, whereas Africa and West Asia have the lowest rates. Asia saw 41% of the world's endometrial cancer diagnoses in 2012, whereas Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, and North America together comprised 48% of diagnoses.<ref name="WCR2014Epi" /> Unlike most cancers, the number of new cases has risen in recent years, including an increase of over 40% in the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United Kingdom|United Kingdom]] between 1993 and 2013.<ref name="Cochrane0514" /> Some of this rise may be due to the increase in obesity rates in developed countries,<ref name="Cochrane0812" /> increasing life expectancies, and lower birth rates.<ref name="Hoffman2" /> The average woman's lifetime risk for endometrial cancer is approximately 2–3%.<ref name="Ma">{{cite journal |last1=Ma |first1=J |last2=Ledbetter |first2=N |last3=Glenn |first3=L |year=2013 |title=Testing women with endometrial cancer for lynch syndrome: should we test all? |journal=Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology |volume=4 |issue=5 |pages=322–30 |doi= |pmid=25032011 |pmc=4093445}}</ref> In the UK, approximately 7,400 cases are diagnosed annually, and in the EU, approximately 88,000.<ref name="Colombo">{{cite journal |last1=Colombo |first1 = N |last2 = Preti |first2 = E |last3 = Landoni |first3 = F |first4=S |last4=Carinelli |first5=A |last5=Colombo |first6=C |last6=Marini |first7=C |last7=Sessa |title=Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up |journal=Annals of Oncology |volume=24 Suppl 6 |issue= |pages=vi33–8 |date=October 2013 |pmid=24078661 |doi=10.1093/annonc/mdt353 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

Endometrial cancer appears most frequently during [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perimenopause|perimenopause]] and menopause, between the ages of 50 and 65;<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn322" /> overall, 75% of endometrial cancer occurs after menopause.<ref name="Cochrane0412" /> Women younger than 40 make up 5% of endometrial cancer cases and 10–15% of cases occur in women under 50 years of age. This age group is at risk for developing ovarian cancer at the same time.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn322" /> The worldwide [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Median|median]] age of diagnosis is 63 years of age;<ref name="Colombo" /> in the United States, the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Average|average]] age of diagnosis is 60 years of age. White American women are at higher risk for endometrial cancer than Black American women, with a 2.88% and 1.69% lifetime risk respectively.<ref name="Burke1" /> Japanese-American women and American Latina women have a lower rates and Native Hawaiian women have higher rates.<ref name="NIH-Prevention">{{cite web |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/prevention/endometrial/HealthProfessional |title = Endometrial Cancer Prevention |work = PDQ |publisher = NIH |date = 28 February 2014}}</ref> |

|||

==Research== |

|||

There are several experimental therapies for endometrial cancer under research, including immunologic, hormonal, and chemotherapeutic. [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trastuzumab|Trastuzumab]] (Herceptin) has been used in cancers known to be positive for the Her2/neu oncogene, but research is still underway. Immunologic therapies are also under investigation, particularly in uterine papillary serous carcinoma.<ref name="ComprehensiveGyn26">{{cite book |last1=Thaker |first1=PH |last2=Sood |first2=AK |chapter=Molecular Oncology in Gynecologic Cancer |editor-last1=Lentz |editor-first1=GM |editor-last2=Lobo |editor-first2=RA |editor-last3=Gershenson |editor-first3=DM |editor-last4=Katz |editor-first4=VL|displayeditors=4 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |edition=6th |isbn=978-0-323-06986-1 |publisher=[[Mosby (publisher)|Mosby]]}}</ref> |

|||

Cancers can be analyzed using genetic techniques (including [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNA sequencing|DNA sequencing]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immunohistochemistry|immunohistochemistry]]) to determine if certain therapies specific to mutated genes can be used to treat it. [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PARP inhibitor|PARP inhibitor]]s are used to treat endometrial cancer with PTEN mutations,<ref name="WCR2014Epi" /> specifically, mutations that lower the expression of PTEN. The PARP inhibitor shown to be active against endometrial cancer is [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olaparib|olaparib]]. Research is ongoing in this area as of the 2010s.<ref name="Reinbolt">{{cite journal |last1 =Reinbolt |first1 = RE |last2 = Hays |first2 = JL |title=The Role of PARP Inhibitors in the Treatment of Gynecologic Malignancies |journal=Frontiers in Oncology |volume=3 |issue= |pages=237 |year=2013 |pmid=24098868 |pmc=3787651 |doi=10.3389/fonc.2013.00237 |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1 = JM |last2 =Ledermann |first2= JA |last3 = Kohn |first3 = EC |title=PARP Inhibitors for BRCA1/2 mutation-associated and BRCA-like malignancies |journal=Annals of Oncology |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=32–40 |date=January 2014 |pmid=24225019 |doi=10.1093/annonc/mdt384 |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1 =Banerjee |first1 = S |last2 = Kaye |first2 = S |title=PARP inhibitors in BRCA gene-mutated ovarian cancer and beyond |journal=Current Oncology Reports |volume=13 |issue=6 |pages=442–9 |date=December 2011 |pmid=21913063 |doi=10.1007/s11912-011-0193-9 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

Research is ongoing on the use of [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metformin|metformin]], a diabetes medication, in obese women with endometrial cancer before surgery. Early research has shown it to be effective in slowing the rate of cancer cell proliferation.<ref name="Sivalingam" /><ref name="Suh2">{{cite journal |last1=Suh |first1=DH |last2=Kim |first2=JW |last3=Kang |first3=S |last4=Kim |first4=HJ |last5=Lee |first5=KH |year=2014 |title=Major clinical research advances in gynecologic cancer in 2013 |journal=Journal of Gynecologic Oncology |volume=25 |issue=3 |pages=236–248 |doi=10.3802/jgo.2014.25.3.236 |pmid=25045437 |pmc=4102743}}</ref> Preliminary research has shown that preoperative metformin administration can reduce expression of tumor markers. However, long-term use of metformin has not been shown to have a preventative effect against developing cancer, but may improve overall survival.<ref name="Sivalingam">{{cite journal |last1=Sivalingam |first1=VN |last2=Myers |first2=J |last3=Nicholas |first3=S |last4=Balen |first4=AH |last5=Crosbie |first5=EJ |year=2014 |title=Metformin in reproductive health, pregnancy and gynaecological cancer: established and emerging indications |journal=Human Reproduction Update |volume= 20|issue= 6|pages= 853–68|doi=10.1093/humupd/dmu037 |pmid=25013215}}</ref> |

|||

[[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temsirolimus|Temsirolimus]], an mTOR inhibitor, is under investigation as a potential treatment.<ref name="Colombo" /> Research shows that mTOR inhibitors may be particularly effective for cancers with mutations in PTEN.<ref name="WCR2014Epi" /> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ridaforolimus|Ridaforolimus]] (deforolimus) is also being researched as a treatment for people who have previously had chemotherapy. Preliminary research has been promising, and a stage II trial for ridaforolimus was completed by 2013.<ref name="Colombo" /> There has also been research on combined ridaforolimus/progestin treatments for recurrent endometrial cancer.<ref name="CRUKresearch" /> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bevacizumab|Bevacizumab]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrosine kinase inhibitor|tyrosine kinase inhibitor]]s, which inhibit [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angiogenesis|angiogenesis]], are being researched as potential treatments for endometrial cancers with high levels of [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vascular endothelial growth factor|vascular endothelial growth factor]].<ref name="WCR2014Epi" /> [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ixabepilone|Ixabepilone]] is being researched as a possible chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer.<ref name="CRUKresearch" /> Treatments for rare high-grade undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma are being researched, as there is no established standard of care yet for this disease. Chemotherapies being researched include doxorubicin and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ifosfamide|ifosfamide]].<ref name="Hensley2">{{cite journal |author=Hensley ML |title=Uterine sarcomas: histology and its implications on therapy |journal=American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book |volume= |issue= |pages=356–61 |year=2012 |pmid=24451763 |doi=10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.356 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

There is also research in progress on more genes and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biomarker|biomarker]]s that may be linked to endometrial cancer. The protective effect of combined oral contraceptives and the IUD is being investigated. Preliminary research has shown that the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levonorgestrel|levonorgestrel]] IUD placed for a year, combined with 6 monthly injections of [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gonadotropin-releasing hormone|gonadotropin-releasing hormone]], can stop or reverse the progress of endometrial cancer in young women.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Minig|first1=L|last2=Franchi|first2=D|last3=Boveri|first3=S|last4=Casadio|first4=C|last5=Bocciolone|first5=L|last6=Sideri|first6=M|title=Progestin intrauterine device and GnRH analogue for uterus-sparing treatment of endometrial precancers and well-differentiated early endometrial carcinoma in young women.|journal=Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO|date=March 2011|volume=22|issue=3|pages=643–9|pmid=20876910|doi=10.1093/annonc/mdq463}}</ref> An experimental drug that combines a hormone with doxorubicin is also under investigation for greater efficacy in cancers with hormone receptors. Hormone therapy that is effective in treating breast cancer, including use of [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aromatase inhibitor|aromatase inhibitor]]s, is also being investigated for use in endometrial cancer. One such drug is [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anastrozole|anastrozole]], which is currently being researched in hormone-positive recurrences after chemotherapy.<ref name="CRUKresearch">{{cite web |url=http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-help/type/womb-cancer/treatment/whats-new-in-womb-cancer-research |title=Womb cancer research |publisher = Cancer Research UK |work = CancerHelp UK |format= |accessdate=31 August 2014}}</ref> Research into hormonal treatments for endometrial stromal sarcomas is ongoing as well. It includes trials of drugs like [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mifepristone|mifepristone]], a progestin antagonist, and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aminoglutethimide|aminoglutethimide]] and [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letrozole|letrozole]], two aromatase inhibitors.<ref name="Sylvestre2" /> |

|||

Research continues into the best imaging method for detecting and staging endometrial cancer. In surgery, research has shown that complete pelvic lymphadenectomy along with hysterectomy in stage 1 endometrial cancer does not improve survival and increases the risk of negative side effects, including [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lymphedema|lymphedema]]. Other research is exploring the potential of identifying the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sentinel lymph node|sentinel lymph node]]s for biopsy by injecting the tumor with dye that shines under [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infrared|infrared]] light. [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intensity modulated radiation therapy|Intensity modulated radiation therapy]] is currently under investigation, and already used in some centers, for application in endometrial cancer, to reduce side effects from traditional radiotherapy. Its risk of recurrence has not yet been quantified. Research on [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperbaric oxygen therapy|hyperbaric oxygen therapy]] to reduce side effects is also ongoing. The results of the PORTEC 3 trial assessing combining adjuvant radiotherapy with chemotherapy were awaited in late 2014.<ref name="CRUKresearch" /> |

|||

==History and culture== |

|||

Endometrial cancer is not widely known by the general populace, despite its frequency. There is low awareness of the symptoms, which can lead to later diagnosis and worse survival.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/21/womb-cancer-fourth-most-common-women |title = Womb cancer: the most common diagnosis you've never heard of |publisher = The Guardian |accessdate = 29 September 2014 |date = 21 September 2014 |last = Carlisle |first = Daloni}}</ref> |

|||

==<nowiki/>== |

|||

=====<nowiki/>===== |

=====<nowiki/>===== |

||

[[Κατηγορία:Καρκίνος]] |

[[Κατηγορία:Καρκίνος]] |

||

Έκδοση από την 16:00, 6 Δεκεμβρίου 2014

| Καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου | |

|---|---|

Θέση και εξέλιξη του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου | |

| Ειδικότητα | ογκολογία |

| Ταξινόμηση | |

| ICD-10 | C54.1 |

| ICD-9 | 182.0 |

| OMIM | 608089 |

| DiseasesDB | 4252 |

| MedlinePlus | 000910 |

| eMedicine | med/674 radio/253 |

| MeSH | D016889 |

Καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου είναι ο καρκίνος που προκύπτει από το ενδομήτριο (η επένδυση της μήτρας)[1]. Είναι το αποτέλεσμα της ανώμαλης αύξησης των κυττάρων που έχουν την ικανότητα να εισβάλουν ή να εξαπλωθούν σε άλλα μέρη του σώματος[2].Το πρώτο σημάδι είναι πιο συχνά κολπική αιμορραγία που δεν σχετίζεται με την περίοδο της γυναίκας. Άλλα πιθανά συμπτώματα περιλαμβάνουν πόνο κατά την ούρηση ή τη σεξουαλική επαφή, ή πυελικό πόνο. [1] Ο καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου εμφανίζεται πιο συχνά στις δεκαετίες μετά την εμμηνόπαυση. [3]

Περίπου το 40% των περιπτώσεων σχετίζονται με την παχυσαρκία. [4] Ο καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου συνδέεται επίσης με την υπερβολική έκθεση σε οιστρογόνα, υψηλή αρτηριακή πίεση και διαβήτη. [1] Ενώ λαμβάνοντας μόνο οιστρογόνα αυξάνεται ο κίνδυνος του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, λαμβάνοντας μαζί οιστρογόνα και προγεστερόνη σε συνδυασμό , όπως στα αντισυλληπτικά, μειώνεται ο κίνδυνος. [1] [4] 2-5% των περιπτώσεων σχετίζονται με γονίδια που κληρονομούνται από τους γονείς του ατόμου. [4] Ο καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου μερικές φορές αναφέρεται αόριστα ως "καρκίνος της μήτρας" , αν και υπάρχει διακριτή διαφορά από άλλες μορφές του καρκίνου της μήτρας, όπως ο καρκίνος του τραχήλου της μήτρας, σάρκωμα της μήτρας, και ασθένεια τροφοβλάστης. [5] Ο πιο συχνός τύπος καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου είναι το ενδομητριοειδές καρκίνωμα, το οποίο αντιπροσωπεύει περισσότερο από το 80% όλων των περιπτώσεων. [4 ] Ο καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου συνήθως διαγιγνώσκεται με βιοψία του ενδομητρίου ή με τη λήψη δειγμάτων κατά τη διάρκεια μιας διαδικασίας γνωστής ως διαστολή και απόξεση. Το τεστ Παπανικολάου δεν είναι συνήθως επαρκές. [6] Τακτικός έλεγχος δεν ζητείται από γυναίκες χαμηλής επικινδυνότητας.

Η κορυφαία επιλογή θεραπείας για τον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου είναι η κοιλιακή υστερεκτομή (η συνολική αφαίρεση της μήτρας χειρουργικά), μαζί με την αφαίρεση των σαλπίγγων και των ωοθηκών και στις δύο πλευρές, που ονομάζεται αμφοτερόπλευρη σαλπιγγοωοθηκεκτομή. Σε πιο προχωρημένες περιπτώσεις, μπορεί επίσης να συνιστάται ακτινοθεραπεία, χημειοθεραπεία ή ορμονική θεραπεία. Εάν ο καρκίνος βρίσκεται σε αρχικό στάδιο, το αποτέλεσμα είναι ευνοϊκό, [1] και το συνολικό ποσοστό πενταετούς επιβίωσης στις Ηνωμένες Πολιτείες είναι μεγαλύτερο από 80% [2]. Το 2012, 320.000 γυναίκες νόσησαν και απέβιωσαν οι 76.000. [1] Αυτή είναι η τρίτη πιο συχνή αιτία θανάτου από τους γυναικείους καρκίνους των πίσω ωοθηκών και του τραχήλου της μήτρας .. Είναι η πιο συχνή στον αναπτυγμένο κόσμο [1] και είναι η πιο κοινή μορφή καρκίνου του γυναικείου αναπαραγωγικού συστήματος στις ανεπτυγμένες χώρες. [2] Τα ποσοστά καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου έχουν αυξηθεί σε ορισμένες χώρες μεταξύ του 1980 και του 2010. [1] Αυτή η αύξηση πιστεύεται ότι οφείλεται στην αύξηση του αριθμού των ηλικιωμένων και την αύξηση των ποσοστών της παχυσαρκίας. [3]

Ταξινόμηση

Υπάρχουν διάφοροι τύποι καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, συμπεριλαμβανομένων των πιο κοινών ενδομητρίου καρκινώματα, τα οποία χωρίζονται σε Τύπου Ι και Τύπου II υποτύπους. Υπάρχουν επίσης σπανιότερες μορφές, συμπεριλαμβανομένης και ενδομητριοειδούς αδενοκαρκίνωμα, της μήτρας θηλώδες καρκίνωμα ορώδης, και καρκίνωμα της μήτρας σαφής-κυττάρων. [1]

Σημεία και συμπτώματα

Κολπική αιμορραγία ή κηλίδες αίματος στις γυναίκες μετά την εμμηνόπαυση εμφανίζεται στο 90% του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [2] [9] Η αιμορραγία είναι ιδιαίτερα κοινά με αδενοκαρκίνωμα, που συμβαίνουν στο 2/3 του συνόλου των περιπτώσεων. [3] [7] Ανώμαλη της εμμήνου ρύσης ή εξαιρετικά μεγάλη , βαρύ, ή συχνά επεισόδια αιμορραγίας σε γυναίκες πριν από την εμμηνόπαυση μπορεί επίσης να είναι ένα σημάδι του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [7]

Τα συμπτώματα εκτός από αιμορραγία δεν είναι κοινά. Άλλα συμπτώματα περιλαμβάνουν λεπτές άσπρο ή σαφές κολπικό έκκριμα σε μετεμμηνοπαυσιακές γυναίκες. [7] Πιο προχωρημένη νόσο δείχνει πιο εμφανή συμπτώματα ή σημεία που μπορεί να ανιχνευθεί σε μια φυσική εξέταση. Η μήτρα μπορεί να γίνει διευρυμένη ή ο καρκίνος μπορεί να εξαπλωθεί, προκαλώντας κάτω κοιλιακή χώρα ή πυελικό πόνο κράμπες. [7] επώδυνη σεξουαλική επαφή ή επώδυνη ή δύσκολη ούρηση είναι λιγότερο κοινά συμπτώματα του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [4] Η μήτρα μπορεί επίσης να γεμίσει με πύον. [5] Από τις γυναίκες με αυτά τα λιγότερο κοινά συμπτώματα (κολπικό έκκριμα, πυελικό πόνο, και πύον), 10-15% έχουν καρκίνο. [11]

Παράγοντες κινδύνου

Οι παράγοντες κινδύνου για καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου είναι η παχυσαρκία, ο σακχαρώδης διαβήτης, ο καρκίνος του μαστού, η χρήση της ταμοξιφαίνης, αφού ποτέ δεν είχε ένα παιδί, η καθυστερημένη εμμηνόπαυση, τα υψηλά επίπεδα των οιστρογόνων, και την αύξηση της ηλικίας. [10] [11] μελέτες μετανάστευσης (μετανάστευση μελέτες), η οποία να εξετάσει την αλλαγή του κινδύνου του καρκίνου σε πληθυσμούς που διακινούνται μεταξύ των χωρών με διαφορετικά ποσοστά καρκίνου, δείχνουν ότι υπάρχει κάποια περιβαλλοντική συνιστώσα στον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. [7] οι παράγοντες κινδύνου για το περιβάλλον δεν είναι καλά χαρακτηρισμένοι. [7]

Ορμόνες

Οι περισσότεροι από τους παράγοντες κινδύνου για καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου περιλαμβάνει υψηλά επίπεδα οιστρογόνων. Μια εκτιμώμενη σε 40% των περιπτώσεων πιστεύεται ότι σχετίζονται με την παχυσαρκία. [8] Στην παχυσαρκία, η περίσσεια λιπώδους ιστού αυξάνει τη μετατροπή της ανδροστενεδιόνης σε οιστρόνη, ένα οιστρογόνο. Υψηλότερα επίπεδα οιστρόνης στο αίμα προκαλεί λιγότερη ή καθόλου ωορρηξία και εκθέτει το ενδομήτριο για τη συνεχή υψηλά επίπεδα οιστρογόνων. [7] [9] Η παχυσαρκία προκαλεί επίσης λιγότερο οιστρογόνου που πρόκειται να απομακρυνθεί από το αίμα. [13] Το σύνδρομο πολυκυστικών ωοθηκών (PCOS) , η οποία προκαλεί επίσης ακανόνιστη ή όχι ωορρηξία, συνδέεται με υψηλότερα ποσοστά καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου για τους ίδιους λόγους όπως η παχυσαρκία. [7] Ειδικότερα, η παχυσαρκία, ο διαβήτης τύπου II, και την αντίσταση στην ινσουλίνη είναι παράγοντες κινδύνου για τον καρκίνο του τύπου Ι του ενδομητρίου. [10] η παχυσαρκία αυξάνει τον κίνδυνο για καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου κατά 300-400%. [11]

Θεραπεία υποκατάστασης οιστρογόνων κατά την εμμηνόπαυση, όταν δεν είναι ισορροπημένο (ή «αντίθετες») με προγεστερόνη είναι ένας άλλος παράγοντας κινδύνου. Υψηλότερες δόσεις ή μεγαλύτερες περιόδους της θεραπείας με οιστρογόνα έχουν υψηλότερο κίνδυνο καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [13] Οι γυναίκες του χαμηλότερου βάρους διατρέχουν μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο από ομόφωνα οιστρογόνα. [4] Μια μεγαλύτερη περίοδος της γονιμότητας, είτε από νωρίς την πρώτη έμμηνο ρύση ή αργά menopause- είναι επίσης ένας παράγοντας κινδύνου. [16] Αχρησιμοποίητος οιστρογόνα αυξάνει τον κίνδυνο ενός ατόμου του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου με 2-10 φορές, ανάλογα με το βάρος και το μήκος της θεραπείας. [4] σε trans άνδρες που λαμβάνουν τεστοστερόνη και δεν έχουν υποβληθεί σε υστερεκτομή, η μετατροπή της τεστοστερόνης σε οιστρογόνα μέσω ανδροστενεδιόνης μπορεί να οδηγήσει σε υψηλότερο κίνδυνο καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [17]

Γενετική

Οι γενετικές διαταραχές μπορούν επίσης να προκαλέσουν καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Σε γενικές γραμμές, οι γενετικές αιτίες συμβάλλουν στην 2-10% των περιπτώσεων καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [1] [2] σύνδρομο Lynch, μια αυτοσωματική κυρίαρχη γενετική διαταραχή που προκαλεί κυρίως καρκίνο του παχέος εντέρου, προκαλεί επίσης καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, ειδικά πριν από την εμμηνόπαυση. Οι γυναίκες με σύνδρομο Lynch έχουν τον κίνδυνο 40-60% να αναπτύξουν καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, υψηλότερα από τον κίνδυνο της ανάπτυξης ορθοκολικού (εντέρου) ή του καρκίνου των ωοθηκών. [3] των ωοθηκών και του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου αναπτυχθεί ταυτόχρονα σε 20% των ανθρώπων. Καρκίνος του ενδομητρίου αναπτύσσεται σχεδόν πάντοτε πριν από τον καρκίνο του παχέος εντέρου, κατά μέσο όρο, 11 χρόνια πριν από [12] καρκινογένεση στον Lynch σύνδρομο προέρχεται από μια μετάλλαξη στο MLH1 ή / και MLH2:. Τα γονίδια που συμμετέχουν στη διαδικασία της αναντιστοιχίας επισκευή, η οποία επιτρέπει σε ένα κύτταρο για να διορθώσει λάθη στο DNA. [7] Άλλα γονίδια μεταλλαγμένα στο σύνδρομο Lynch περιλαμβάνουν MSH2, MSH6 και PMS2, οι οποίες είναι επίσης αναντιστοιχία γονίδια επισκευής. Οι γυναίκες με το σύνδρομο Lynch αντιπροσωπεύουν το 2-3% των περιπτώσεων καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου? μερικές πηγές τοποθετούν αυτό τόσο υψηλό όπως 5%. [12] [5] Ανάλογα με τη μετάλλαξη γονιδίων, οι γυναίκες με σύνδρομο Lynch έχουν διαφορετικές κίνδυνοι για καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Με MLH1 μεταλλάξεις, ο κίνδυνος είναι 54%? με MSH2, 21%? και με MSH6, 16%. [6]

Οι γυναίκες με οικογενειακό ιστορικό καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου είναι σε μεγαλύτερο κίνδυνο. [7] Δύο γονίδια πιο συχνά συνδέονται με ορισμένες άλλες γυναικείες μορφές καρκίνου, το BRCA1 και BRCA2, δεν προκαλούν καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Υπάρχει μια εμφανής σχέση με αυτά τα γονίδια, αλλά αυτό οφείλεται στη χρήση της ταμοξιφαίνης, ένα φάρμακο που το ίδιο μπορεί να προκαλέσει καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, σε καρκίνους μαστού και ωοθήκης. [7] Η κληρονομική σύνδρομο Cowden γενετική κατάσταση μπορεί επίσης να προκαλέσει καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Οι γυναίκες με αυτή τη διαταραχή έχουν κίνδυνο ζωής 5-10% της ανάπτυξης του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, [4], σε σύγκριση με τον κίνδυνο 2-3% για ανεπηρέαστες γυναίκες. [12]

Άλλα προβλήματα υγείας

Ορισμένες θεραπείες για άλλες μορφές καρκίνου αυξάνουν τον κίνδυνο διάρκειας ζωής του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, η οποία είναι μια βασική 2-3%. [1] Tamoxifen, ένα φάρμακο που χρησιμοποιείται για τη θεραπεία οιστρογόνων θετικούς καρκίνους του μαστού, έχει συσχετισθεί με τον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου σε περίπου 0,1% των χρηστών, ιδίως των ηλικιωμένων γυναικών, αλλά τα οφέλη για την επιβίωση από την ταμοξιφαίνη γενικά αντισταθμίζει τον κίνδυνο καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [20] μια πορεία 1-2 έτος ταμοξιφαίνη περίπου διπλασιάζει τον κίνδυνο καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, και ένα 5-ετή πορεία της θεραπείας τετραπλασιάζει ο κίνδυνος αυτός. [3] η ραλοξιφαίνη, ένα παρόμοιο φάρμακο, δεν αυξάνει τον κίνδυνο καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. [4] Προηγουμένως έχουν καρκίνο των ωοθηκών είναι ένας παράγοντας κινδύνου για καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, [22], όπως ότι είχε προηγούμενη ακτινοθεραπεία στην πύελο. Συγκεκριμένα, οι όγκοι των ωοθηκών κοκκιωδών κυττάρων και θηκώματα είναι όγκοι που σχετίζονται με τον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Χαμηλή ανοσολογική λειτουργία έχει επίσης ενοχοποιηθεί στον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. [6] Η υψηλή αρτηριακή πίεση είναι επίσης ένας παράγοντας κινδύνου, [7], αλλά αυτό μπορεί να είναι λόγω της σύνδεσής του με την παχυσαρκία. [8]

Προστατευτικοί παράγοντες

Το κάπνισμα και η χρήση της προγεστερόνης είναι τα δύο προστατευτικά έναντι του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. Το κάπνισμα παρέχει προστασία αλλάζοντας τον μεταβολισμό των οιστρογόνων και την προώθηση της απώλειας βάρους και πρόωρη εμμηνόπαυση. Αυτό το προστατευτικό αποτέλεσμα διαρκεί μεγάλο χρονικό διάστημα μετά το κάπνισμα έχει διακοπεί. Προγεστίνης είναι παρούσα στο συνδυασμένο από του στόματος αντισυλληπτικό χάπι και το ορμονικό ενδομήτρια συσκευή (IUD) [1] συνδυασμένα από του στόματος αντισυλληπτικά μειώνουν τον κίνδυνο περισσότερο η μακρόχρονη λήψη:. Κατά 56% μετά από 4 χρόνια, το 67% μετά από 8 χρόνια, και το 72% μετά και 12 χρόνια. Αυτή η μείωση του κινδύνου συνεχίζεται για τουλάχιστον 15 έτη μετά τη χρήση αντισυλληπτικών έχει σταματήσει. [21] Οι παχύσαρκες γυναίκες μπορεί να χρειαστούν υψηλότερες δόσεις προγεστερόνης να προστατεύονται. [7] Αφού είχε περισσότερο από 5 βρέφη (ο μεγάλος αριθμός γεννήσεων) είναι επίσης ένας προστατευτικός παράγοντας, [3], και έχει τουλάχιστον ένα παιδί μειώνει τον κίνδυνο κατά 35%. Ο θηλασμός για περισσότερο από 18 μήνες μειώνει τον κίνδυνο κατά 23%. Η αυξημένη σωματική δραστηριότητα μειώνει τον κίνδυνο ενός ατόμου από 38-46%. Υπάρχει μια προκαταρκτική απόδειξη ότι η κατανάλωση της σόγιας είναι προστατευτική. [21]

Παθοφυσιολογία

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ενδομητρίου μορφές καρκίνου όταν υπάρχουν σφάλματα στην κανονική ανάπτυξη του ενδομητρίου κυττάρου. Συνήθως, όταν τα κύτταρα γεράσουν ή να καταστραφεί, να πεθάνουν, και νέα κύτταρα παίρνουν τη θέση τους. Καρκίνος ξεκινά όταν τα νέα κύτταρα σχηματίζουν αχρείαστα, και παλιά ή κατεστραμμένα κύτταρα δεν πεθαίνουν, όπως θα έπρεπε. Η συσσώρευση επιπλέον κυττάρων συχνά σχηματίζει μια μάζα ιστού που ονομάζεται μια αύξηση ή όγκου. Αυτά τα ανώμαλα καρκινικά κύτταρα έχουν πολλές γενετικές ανωμαλίες που προκαλούν τους για να αυξηθεί υπερβολικά. [1]

Σε 10-20% των καρκίνων του ενδομητρίου, κυρίως Βαθμού 3 (το υψηλότερο βαθμό ιστολογική), οι μεταλλάξεις βρίσκονται σε ένα γονίδιο καταστολέα όγκου, συνήθως ρ53 ή ΡΤΕΝ. Στο 20% των ενδομήτριων υπερπλασίες και το 50% των καρκίνων ενδομητριοειδές, ΡΤΕΝ υποφέρει μία μετάλλαξη απώλειας λειτουργίας ή μια μηδενική μετάλλαξη, καθιστώντας το λιγότερο αποτελεσματικό ή τελείως αναποτελεσματική. [24] Η απώλεια της λειτουργίας του ΡΤΕΝ οδηγεί σε άνω-ρύθμιση της ΡΙ3Κ / Akt / mTOR μονοπάτι, το οποίο προκαλεί την ανάπτυξη των κυττάρων. [3] Το μονοπάτι ρ53 μπορεί είτε να κατασταλεί ή εξαιρετικά ενεργοποιημένα στον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. Όταν μια μεταλλαγμένη εκδοχή του ρ53 υπερεκφράζεται, ο καρκίνος τείνει να είναι ιδιαίτερα επιθετική. [24] Ρ53 μεταλλάξεων και χρωμοσωμικών αστάθεια συνδέονται με ορώδης καρκινώματα, τα οποία τείνουν να μοιάζουν ωοθηκών και ωαγωγών καρκινωμάτων. Οι ορώδες καρκίνωμα φαίνεται να αναπτύξουν από ενδομητρίου ενδοεπιθηλιακή καρκίνωμα. [15]

ΡΤΕΝ και ρ27 μεταλλάξεις απώλειας λειτουργίας συνδέονται με μια καλή πρόγνωση, ιδιαίτερα σε παχύσαρκες γυναίκες. Το HER2 / neu ογκογονιδίου, το οποίο δείχνει μια κακή πρόγνωση, εκφράζεται στο 20% των ενδομητριοειδές και ορώδες καρκίνωμα. CTNNB1 (βήτα-κατενίνης? Ένα γονίδιο μεταγραφής) Οι μεταλλάξεις που βρίσκονται σε 14-44% των καρκίνων του ενδομητρίου και μπορεί να υποδεικνύουν μία καλή πρόγνωση, αλλά τα δεδομένα είναι σαφές είναι [24] Βήτα-κατενίνη μεταλλάξεις που βρίσκονται συνήθως σε καρκίνους ενδομητρίου με πλακώδη κύτταρα. .. οι [15] FGFR2 μεταλλάξεις που βρίσκονται σε περίπου 10% των καρκίνων του ενδομητρίου, και προγνωστική σημασία τους δεν είναι σαφής [24] είναι μια άλλη SPOP ογκοκατασταλτικό γονίδιο βρέθηκε να μεταλλαχθεί σε ορισμένες περιπτώσεις, του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου: 9% διαυγούς κυττάρου ενδομητρίου καρκινώματα και 8% των ορώδες καρκίνωμα του ενδομητρίου έχουν μεταλλάξεις σε αυτό το γονίδιο. [25]

Τύπου Ι και καρκίνους Τύπου II (εξηγείται παρακάτω) τείνουν να έχουν διαφορετικές μεταλλάξεις που εμπλέκονται. ARID1A, τα οποία συχνά φέρει μία σημειακή μετάλλαξη σε Τύπου Ι καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, επίσης μεταλλαγμένο στο 26% των σαφών καρκινώματα του ενδομητρίου, και 18% των ορώδους καρκινωμάτων. Οι επιγενετική σίγηση και σημειακές μεταλλάξεις διαφόρων γονιδίων που βρίσκονται συνήθως σε Τύπου Ι καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. [5] [6] Μεταλλάξεις σε γονίδια καταστολής όγκων είναι κοινά σε Τύπου II καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. [4] PIK3CA συνήθως μεταλλάσσεται τόσο Τύπου Ι και Τύπου II καρκίνους. [23] Σε γυναίκες με Lynch σύνδρομο που σχετίζεται με καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, μικροδορυφορική αστάθεια είναι κοινή. [15]

Ανάπτυξη του ενδομητρίου υπερπλασίας (υπερανάπτυξη του ενδομητρίου κύτταρα) είναι ένας σημαντικός παράγοντας κινδύνου, επειδή υπερπλασίες μπορούν και συχνά αναπτύσσουν σε αδενοκαρκίνωμα, αν και ο καρκίνος μπορεί να αναπτυχθεί χωρίς την παρουσία ενός υπερπλασία. [7] Εντός 10 χρόνια, 8-30% των άτυπων ενδομητρίου υπερπλασίες εξελιχθούν σε καρκίνο, ενώ 1-3% των μη άτυπων υπερπλασιών πράξουν. [26] μία άτυπη υπερπλασία είναι μία με ορατές ανωμαλίες στους πυρήνες. Τα προ-καρκινικές ενδομητρίου υπερπλασίες που αναφέρεται επίσης ως ενδομητρίου ενδοεπιθηλιακή νεοπλασία. [9] Μεταλλάξεις στο γονίδιο KRAS μπορεί να προκαλέσει υπερπλασία του ενδομητρίου και επομένως Τύπου Ι καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου. [24] υπερπλασία του ενδομητρίου τυπικά συμβαίνει μετά την ηλικία των 40. [5] του ενδομητρίου αδενική δυσπλασία συμβαίνει με υπερέκφραση της ρ53, και αναπτύσσεται σε ορώδης καρκίνωμα. [10]

Διάγνωση

![An ultrasound image showing an endometrial fluid accumulation (darker area) in a [[1]] woman, a finding that is highly suspicious for endometrial cancer](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Endometrial_fluid_accumulation%2C_postmenopausal.jpg/220px-Endometrial_fluid_accumulation%2C_postmenopausal.jpg)

Διάγνωση του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου γίνεται για πρώτη φορά από μια φυσική εξέταση και διαστολή και απόξεση (αφαίρεση του ενδομήτριου ιστού). Αυτός ο ιστός στη συνέχεια εξετάζονται ιστολογικά για τα χαρακτηριστικά του καρκίνου. Αν βρεθεί ο καρκίνος, ιατρική απεικόνιση μπορεί να γίνει για να δούμε αν ο καρκίνος έχει εξαπλωθεί ή εισέβαλε ιστού.

Εξέταση

Έλεγχο ρουτίνας του ασυμπτωματικές γυναίκες δεν ενδείκνυται, επειδή η ασθένεια είναι εξαιρετικά ιάσιμη σε πρώιμο, συμπτωματική στάδια. Αντ 'αυτού, οι γυναίκες, ιδιαίτερα γυναίκες στην εμμηνόπαυση, πρέπει να γνωρίζουν τα συμπτώματα και τους παράγοντες κινδύνου καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου. Μια δοκιμασία διαλογής του τραχήλου της μήτρας, όπως ένα τεστ Παπανικολάου, δεν είναι ένα χρήσιμο διαγνωστικό εργαλείο για τον καρκίνο του ενδομητρίου, επειδή το επίχρισμα θα είναι κανονικά το 50% του χρόνου. [1] Ενα τεστ Παπανικολάου μπορεί να ανιχνεύσει ασθένεια που έχει εξαπλωθεί στον τράχηλο. [2 ] τα αποτελέσματα από μια πυελική εξέταση είναι συχνά φυσιολογική, ιδιαίτερα στα πρώτα στάδια της νόσου. Αλλαγές στο μέγεθος, το σχήμα ή τη συνοχή της μήτρας ή / και τον περιβάλλοντα, υποστηρικτικών δομών του μπορεί να υπάρχουν όταν η νόσος είναι πιο προχωρημένη. [1] στένωση του τραχήλου, η στένωση του τραχήλου της μήτρας άνοιγμα, είναι ένα σημάδι του καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου, όταν πύον ή αίμα βρέθηκε συλλέγονται στη μήτρα (πυομήτρας ή hematometra). [3]

Οι γυναίκες με το σύνδρομο Lynch θα πρέπει να αρχίσει να έχει ετήσιος έλεγχος βιοψία στην ηλικία των 35. Μερικές γυναίκες με σύνδρομο Lynch να επιλέξουν την προφυλακτική υστερεκτομή και σαλπιγγοεκτομή να μειώσει σημαντικά τον κίνδυνο καρκίνου του ενδομητρίου και των ωοθηκών. [1]