Οστεοαρθρίτιδα: Διαφορά μεταξύ των αναθεωρήσεων

Νέα σελίδα: {{Infobox disease | Name = Οστεοαρθρίτις | Image = Gonarthrose-Knorpelaufbrauch.jpg | Caption = | DiseasesDB = 9313 | ... Ετικέτα: μεγάλη προσθήκη |

(Καμία διαφορά)

|

Έκδοση από την 20:58, 20 Νοεμβρίου 2012

| Οστεοαρθρίτιδα | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ειδικότητα | οικογενειακή ιατρική, Ορθοπεδική και ρευματολογία |

| Συμπτώματα | αρθρίτιδα[1] |

| Ταξινόμηση | |

| ICD-10 | M15-M19, M47 |

| ICD-9 | 715 |

| OMIM | 165720 |

| DiseasesDB | 9313 |

| MedlinePlus | 000423 |

| eMedicine | med/1682 orthoped/427 pmr/93 radio/492 |

| MeSH | D010003 |

«Οστεοαρθρίτιδα (ΟΑ), επίσης γνωστή ως εκφυλιστική αρθρίτιδα 'ή εκφυλιστική νόσος των αρθρώσεων 'ή οστεοαρθρίτιδα», είναι μια ομάδα μηχανικών ανωμαλίες συνεπάγονται υποβάθμιση της κοινή s, Σφάλμα αναφοράς: Λείπει η ετικέτα κλεισίματος </ref> για την ετικέτα <ref> including articular cartilage and subchondral bone. Symptoms may include joint pain, tenderness, stiffness, locking, and sometimes an effusion. A variety of causes—hereditary, developmental, metabolic, and mechanical—may initiate processes leading to loss of cartilage. When bone surfaces become less well protected by cartilage, bone may be exposed and damaged. As a result of decreased movement secondary to pain, regional muscles may atrophy, and ligaments may become more lax.[2]

Treatment generally involves a combination of exercise, lifestyle modification, and analgesics. If pain becomes debilitating, joint replacement surgery may be used to improve the quality of life. OA is the most common form of arthritis,[2] and the leading cause of chronic disability in the United States.[3] It affects about 8 million people in the United Kingdom and nearly 27 million people in the United States.[εκκρεμεί παραπομπή]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom is pain, causing loss of ability and often stiffness. "Pain" is generally described as a sharp ache, or a burning sensation in the associate muscles and tendons. OA can cause a crackling noise (called "crepitus") when the affected joint is moved or touched, and patients may experience muscle spasm and contractions in the tendons. Occasionally, the joints may also be filled with fluid. Humid and cold weather increases the pain in many patients.[4][5]

OA commonly affects the hands, feet, spine, and the large weight bearing joints, such as the hips and knees, although in theory, any joint in the body can be affected. As OA progresses, the affected joints appear larger, are stiff and painful, and usually feel better with gentle use but worse with excessive or prolonged use, thus distinguishing it from rheumatoid arthritis.

In smaller joints, such as at the fingers, hard bony enlargements, called Heberden's nodes (on the distal interphalangeal joints) and/or Bouchard's nodes (on the proximal interphalangeal joints), may form, and though they are not necessarily painful, they do limit the movement of the fingers significantly. OA at the toes leads to the formation of bunions, rendering them red or swollen. Some people notice these physical changes before they experience any pain.

OA is the most common cause of joint effusion, sometimes called water on the knee in lay terms, an accumulation of excess fluid in or around the knee joint.[6]

Causes

Some investigators believe that mechanical stress on joints underlies all osteoarthritis, with many and varied sources of mechanical stress, including misalignments of bones caused by congenital or pathogenic causes; mechanical injury; overweight; loss of strength in muscles supporting joints; and impairment of peripheral nerves, leading to sudden or uncoordinated movements that overstress joints.[7] However exercise, including running in the absence of injury, has not been found to increase one's risk of developing osteoarthritis.[8] Nor has cracking ones knuckles been found to play a role.[9]

Primary

Primary osteoarthritis is a chronic degenerative disorder related to but not caused by aging, as there are people well into their nineties who have no clinical or functional signs of the disease. As a person ages, the water content of the cartilage decreases[10] as a result of a reduced proteoglycan content, thus causing the cartilage to be less resilient. Without the protective effects of the proteoglycans, the collagen fibers of the cartilage can become susceptible to degradation and thus exacerbate the degeneration. Inflammation of the surrounding joint capsule can also occur, though often mild (compared to what occurs in rheumatoid arthritis). This can happen as breakdown products from the cartilage are released into the synovial space, and the cells lining the joint attempt to remove them. New bone outgrowths, called "spurs" or osteophytes, can form on the margins of the joints, possibly in an attempt to improve the congruence of the articular cartilage surfaces. These bone changes, together with the inflammation, can be both painful and debilitating.

A number of studies have shown that there is a greater prevalence of the disease among siblings and especially identical twins, indicating a hereditary basis.[11] Up to 60% of OA cases are thought to result from genetic factors.

Both primary generalized nodal OA and erosive OA (EOA. also called inflammatory OA) are sub-sets of primary OA. EOA is a much less common, and more aggressive inflammatory form of OA which often affects the distal interphalangeal joints and has characteristic changes on x-ray.

Secondary

This type of OA is caused by other factors but the resulting pathology is the same as for primary OA:

- Alkaptonuria

- Congenital disorders of joints

- Diabetes.

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease

- Inflammatory diseases (such as Perthes' disease), (Lyme disease), and all chronic forms of arthritis (e.g. costochondritis, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis). In gout, uric acid crystals cause the cartilage to degenerate at a faster pace.

- Injury to joints or ligaments (such as the ACL), as a result of an accident or orthodontic operations.

- Ligamentous deterioration or instability may be a factor.

- Marfan syndrome

- Obesity

- Septic arthritis (infection of a joint )

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made with reasonable certainty based on history and clinical examination.[12][13] X-rays may confirm the diagnosis. The typical changes seen on X-ray include: joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis (increased bone formation around the joint), subchondral cyst formation, and osteophytes.[14] Plain films may not correlate with the findings on physical examination or with the degree of pain.[15] Usually other imaging techniques are not necessary to clinically diagnose osteoarthritis.

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology, using data from a multi-center study, developed a set of criteria for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis based on hard tissue enlargement and swelling of certain joints. These criteria were found to be 92% sensitive and 98% specific for hand osteoarthritis versus other entities such as rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathies.[16]

Related pathologies whose names may be confused with osteoarthritis include pseudo-arthrosis. This is derived from the Greek words pseudo, meaning "false", and arthrosis, meaning "joint." Radiographic diagnosis results in diagnosis of a fracture within a joint, which is not to be confused with osteoarthritis which is a degenerative pathology affecting a high incidence of distal phalangeal joints of female patients. A polished ivory-like appearance may also develop on the bones of the affected joints, reflecting a change calledeburnation.[17]

-

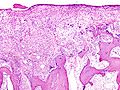

Damaged cartilage in gross pathological specimen from sows. (a) cartilage erosion (b)cartilage ulceration (c)cartilage repair (d)osteophyte (bone spur) formation.

-

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female.

-

Severe osteoarthritis and osteopenia of the carpal joint and 1st carpometacarpel joint.

Classification

Osteoarthritis can be classified into either primary or secondary depending on whether or not there is an identifiable underlying cause.

Management

Lifestyle modification (such as weight loss and exercise) and analgesics are the mainstay of treatment. Acetaminophen / paracetamol is used first line and NSAIDs are only recommended as add on therapy if pain relief is not sufficient.[18] This is due to the relative greater safety of acetaminophen.[18]

Lifestyle modification

For overweight people, weight loss may be an important factor. Patient education has been shown to be helpful in the self-management of arthritis. It decreases pain, improving function, reducing stiffness and fatigue, and reducing medical usage.[19] A meta-analysis has shown patient education can provide on average 20% more pain relief when compared to NSAIDs alone in patients with hip OA.[19]

Physical measures

For most people with OA, graded exercise should be the mainstay of their self-management. Moderate exercise leads to improved functioning and decreased pain in people with osteoarthritis of the knee.[19][8] While there is some evidence for certain physical therapies evidence for the combined program is limited.[20]

There is sufficient evidence to indicate that physical interventions can reduce pain and improve function.[21] There is some evidence that manual therapy is more effective than exercise for the treatment of hip osteoarthritis, however this evidence could be considered to be inconclusive.[22] Functional, gait, and balance training has been recommended to address impairments of proprioception, balance, and strength in individuals with lower extremity arthritis as these can contribute to higher falls in older individuals.[23] Splinting of the base of the thumb for OA leads to improvements after one year.[24]

Medication

- Analgesics

Acetaminophen is the first line treatment for OA.[18][25] For mild to moderate symptoms effectiveness is similar to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), though for more severe symptoms NSAIDs may be more effective.[18] NSAIDs such as ibuprofen while more effective in severe cases are associated with greater side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding.[18] Another class of NSAIDs, COX-2 selective inhibitors (such as celecoxib) are equally effective to NSAIDs with lower rates of adverse gastrointestinal adverse effects but higher rates of cardiovascular disease such as myocardial infarction.[26] They are also much more expensive. There are several NSAIDs available for topical use including diclofenac. They have fewer systemic side-effects and at least some therapeutic effect.[27] While opioid analgesic such as morphine and fentanyl improve pain this benefit is outweighed by frequent adverse events and thus they should not routinely be used.[28]

- Other

Oral steroids are not recommended in the treatment of OA because of their modest benefit and high rate of adverse effects. Injection of glucocorticoids (such as hydrocortisone) leads to short term pain relief that may last between a few weeks and a few months.[29] Topical capsaicin and joint injections of hyaluronic acid have not been found to lead to significant improvement.[27][30] Hyaluronic acid injects have been associated with significant harm.[30]

Surgery

If disability is significant and the above management is ineffective, joint replacement surgery or resurfacing may be recommended. Evidence supports joint replacement for both knees and hips.[31] For the knee it improves both pain and functioning.[32] Arthroscopic surgical intervention for osteoarthritis of the knee however has been found to be no better than placebo at relieving symptoms.[33]

Alternative medicine

Many alternative medicines are purporting to decrease pain associated with arthritis. However, there is little evidence supporting benefits for most alternative treatments including: vitamin A, C, and E, ginger, turmeric, omega-3 fatty acids, chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine. These treatments are thus not recommended.[34][35] Glucosamine was once believed to be effective,[36] but a recent analysis has found that it is no better than placebo.[37] S-Adenosyl methionine may relieve pain similar to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[36][38] While electrostimulation techniques (NEST) have been used for twenty years to treat osteoarthritis in the knee, there is no evidence to show that it reduces pain or disability.[39] Three studies support the use of cat's claw.[34]

- Acupuncture

A Cochrane review found that while acupuncture leads to a statistically significant improvement in pain relief, this improvement is small and may be of questionable clinical significance. Waiting list-controlled trials for peripheral joint osteoarthritis do show clinically relevant benefits, but these may be due to placebo effects.[40] Acupuncture does not seem to produce long-term benefits.[41]

- Glucosamine

Controversy surrounds glucosamine.[42] A 2010 meta-analysis has found that it is no better than placebo.[37] Some older reviews conclude that glucosamine sulfate was an effective treatment[43][44] while some others have found it ineffective.[45][46] A difference has been found between trials involving glucosamine sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride, with glucosamine sulfate showing a benefit and glucosamine hydrochloride not. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) recommends that glucosamine be discontinued if no effect is observed after six months.[47]

Epidemiology

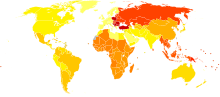

no data ≤ 200 200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 | 300–320 320–340 340–360 360–380 380–400 ≥ 400 |

Osteoarthritis affects nearly 27 million people in the United States, accounting for 25% of visits to primary care physicians, and half of all NSAID prescriptions. It is estimated that 80% of the population have radiographic evidence of OA by age 65, although only 60% of those will have symptoms.[49] In the United States, hospitalizations for osteoarthritis increased from 322,000 in 1993 to 735,000 in 2006.[50]

Globally osteoarthritis causes moderate to severe disability in 43.4 million people as of 2004.[51]

Etymology

Osteoarthritis is derived from the Greek word part osteo-, meaning "of the bone", combined with arthritis: arthr-, meaning "joint", and -itis, the meaning of which has come to be associated with inflammation. The -itis of osteoarthritis could be considered misleading as inflammation is not a conspicuous feature. Some clinicians refer to this condition as osteoarthosis to signify the lack of inflammatory response.

History

Evidence for osteoarthritis found in the fossil record is studied by paleopathologists, specialists in ancient disease and injury. Osteoarthritis has been reported in fossils of the large carnivorous dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis.[52]

Research

There are ongoing efforts to determine if there are agents that modify outcomes in osteoarthritis. There is tentative evidence that strontium ranelate may decrease degeneration in osteoarthritis and improve outcomes.[53][54]

References

- ↑ (Αγγλικά) οντολογία των ασθενειών. 27 Μαΐου 2016. purl

.obolibrary .org /obo /doid .owl. Ανακτήθηκε στις 30 Νοεμβρίου 2020. - ↑ 2,0 2,1 Conaghan, Phillip. «Osteoarthritis — National clinical guideline for care and management in adults» (PDF). Ανακτήθηκε στις 29 Απριλίου 2008.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (February 2001). «Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999». MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 50 (7): 120–5. PMID 11393491.

- ↑ McAlindon T., Formica M., Schmid C.H., Fletcher J. (2007). «Changes in barometric pressure and ambient temperature influence osteoarthritis pain». The American Journal of Medicine 120 (5): 429–434. doi:. PMID 17466654. http://eclips.consult.com/eclips/article/Medicine/S0084-3873(08)79099-0.

- ↑ Πρότυπο:MedlinePlus

- ↑ Water on the knee, MayoClinic.com

- ↑ Brandt KD, Dieppe P, Radin E (January 2009). «Etiopathogenesis of osteoarthritis». Med. Clin. North Am. 93 (1): 1–24, xv. doi:. PMID 19059018.

- ↑ 8,0 8,1 Bosomworth NJ (September 2009). «Exercise and knee osteoarthritis: benefit or hazard?». Can Fam Physician 55 (9): 871–8. PMID 19752252.

- ↑ Deweber, K; Olszewski, M, Ortolano, R (Mar-Apr 2011). «Knuckle cracking and hand osteoarthritis.». Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM 24 (2): 169–74. doi:. PMID 21383216.

- ↑ Simon, H (8 Μαΐου 2005). «Osteoarthritis». University of Maryland Medical Center. Ανακτήθηκε στις 25 Απριλίου 2009. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (βοήθεια) - ↑ Valdes AM, Spector TD (August 2008). «The contribution of genes to osteoarthritis». Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 34 (3): 581–603. doi:. PMID 18687274.

- ↑ Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G και άλλοι. (March 2010). «EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis». Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 (3): 483–9. doi:. PMID 19762361.

- ↑ Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Oster JD, Bernsen RM, Verhaar JA, Ginai AZ, Bohnen AM (August 2002). «Joint space narrowing and relationship with symptoms and signs in adults consulting for hip pain in primary care». J. Rheumatol. 29 (8): 1713–8. PMID 12180735. http://www.jrheum.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12180735.

- ↑ Πρότυπο:MerckManual

- ↑ Phillips CR, Brasington RD (2010). «Osteoarthritis treatment update: Are NSAIDs still in the picture?». Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine 27 (2). http://www.musculoskeletalnetwork.com/display/article/1145622/1517357.

- ↑ Altman R, Alarcón G, Appelrouth D και άλλοι. (1990). «The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand». Arthritis Rheum. 33 (11): 1601–10. doi:. PMID 2242058.

- ↑ Neil Vasan; Le, Tao; Bhushan, Vikas (2010). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, 2010 (First Aid USMLE). McGraw-Hill Medical. σελ. 378. ISBN 0-07-163340-5.

- ↑ 18,0 18,1 18,2 18,3 18,4 Flood J (March 2010). «The role of acetaminophen in the treatment of osteoarthritis». Am J Manag Care 16 (Suppl Management): S48–54. PMID 20297877.

- ↑ 19,0 19,1 19,2 Cibulka MT, White DM, Woehrle J, et al. (April 2009). «Hip pain and mobility deficits—hip osteoarthritis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association». J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 39 (4): A1–25. doi:. PMID 19352008.

- ↑ Wang, SY; Olson-Kellogg, B; Shamliyan, TA; Choi, JY; Ramakrishnan, R; Kane, RL (2012 Nov 6). «Physical therapy interventions for knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis: a systematic review.». Annals of internal medicine 157 (9): 632-44. PMID 23128863.

- ↑ Page CJ, Hinman RS, Bennell KL (2011). «Physiotherapy management of knee osteoarthritis». Int J Rheum Dis 14 (2): 145–152. doi:. PMID 21518313.

- ↑ French HP, Brennan A, White B, Cusack T (2011). «Manual therapy for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee — a systematic review». Man Ther 16 (2): 109–117. doi:. PMID 21146444.

- ↑ Sturnieks DL, Tiedemann A, Chapman K, Munro B, Murray SM, Lord SR (November 2004). «Physiological risk factors for falls in older people with lower limb arthritis». J. Rheumatol. 31 (11): 2272–9. PMID 15517643. http://www.jrheum.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15517643.

- ↑ Rannou F, Dimet J, Boutron I, et al. (May 2009). «Splint for base-of-thumb osteoarthritis: a randomized trial». Ann. Intern. Med. 150 (10): 661–9. PMID 19451573. http://www.annals.org/article.aspx?volume=150&page=661.

- ↑ Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G και άλλοι. (September 2007). «OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence». Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15 (9): 981–1000. doi:. PMID 17719803.

- ↑ Chen, YF; Jobanputra, P; Barton, P; Bryan, S; Fry-Smith, A; Harris, G; Taylor, RS (April 2008). «Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation.». Health technology assessment 12 (11): 1–278, iii. PMID 18405470.

- ↑ 27,0 27,1 Altman R, Barkin RL (March 2009). «Topical therapy for osteoarthritis: clinical and pharmacologic perspectives». Postgrad Med 121 (2): 139–47. doi:. PMID 19332972.

- ↑ Nüesch E, Rutjes AW, Husni E, Welch V, Jüni P (2009). Nüesch, Eveline, επιμ. «Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip». Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003115. doi:. PMID 19821302.

- ↑ Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F (April 2004). «Corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis of the knee: meta-analysis». BMJ 328 (7444): 869. doi:. PMID 15039276.

- ↑ 30,0 30,1 Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S (August 2012). «Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis». Ann. Intern. Med. 157 (3): 180–91. doi:. PMID 22868835. http://www.annals.org/article.aspx?volume=157&page=180.

- ↑ Santaguida, PL; Hawker, GA, Hudak, PL, Glazier, R, Mahomed, NN, Kreder, HJ, Coyte, PC, Wright, JG (December 2008). «Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review». Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie 51 (6): 428–36. PMID 19057730.

- ↑ Carr, AJ; Robertsson, O; Graves, S; Price, AJ; Arden, NK; Judge, A; Beard, DJ (7 April 2012). «Knee replacement». Lancet 379 (9823): 1331–40. doi:. PMID 22398175.

- ↑ Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ και άλλοι. (2002). «A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee is proven to bring an improvement lasting for about two years». The New England Journal of Medicine 347 (2): 81–8. doi:. PMID 12110735. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/347/2/81.

- ↑ 34,0 34,1 Rosenbaum CC, O'Mathúna DP, Chavez M, Shields K (2010). «Antioxidants and antiinflammatory dietary supplements for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis». Altern Ther Health Med 16 (2): 32–40. PMID 20232616.

- ↑ Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Scherer M και άλλοι. (2007). «Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip». Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (8): 580–90. PMID 17438317.

- ↑ 36,0 36,1 Hardy ML, Coulter I, Morton SC και άλλοι. (August 2003). «S-adenosyl-L-methionine for treatment of depression, osteoarthritis, and liver disease». Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) (64): 1–3. PMID 12899148.

- ↑ 37,0 37,1 Wandel S, Jüni P, Tendal B, et al. (2010). «Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with [http://www.acumio.com/dealing-osteoarthritis-guide-afflicted-individuals-485.html osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis»]. BMJ 341: c4675. doi:. PMID 20847017.

- ↑ De Silva, V; El-Metwally, A, Ernst, E, Lewith, G, Macfarlane, GJ, Arthritis Research UK Working Group on Complementary and Alternative, Medicines (May 2011). «Evidence for the efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines in the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review». Rheumatology 50 (5): 911–20. doi:. PMID 21169345.

- ↑ Rutjes AW, Nüesch E, Sterchi R και άλλοι. (2009). Rutjes, Anne WS, επιμ. «Transcutaneous electrostimulation for osteoarthritis of the knee». Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD002823. doi:. PMID 19821296.

- ↑ Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K και άλλοι. (2010). Manheimer, Eric, επιμ. «Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis». Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001977. doi:. PMID 20091527.

- ↑ Wang, S; Kain ZN; White PF (2008). «Acupuncture Analgesia: II. Clinical Considerations». Anesth Analg 106 (2): 611–21. doi:. PMID 18227323. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/.../file/Acupuncture.../CD001977.pdf.

- ↑ The effects of Glucosamine Sulphate on OA of the knee joint. BestBets.

- ↑ Poolsup N, Suthisisang C, Channark P, Kittikulsuth W (2005). «Glucosamine long-term treatment and the progression of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review of randomized controlled trials». The Annals of pharmacotherapy 39 (6): 1080–7. doi:. PMID 15855241.

- ↑ Black C, Clar C, Henderson R και άλλοι. (November 2009). «The clinical effectiveness of glucosamine and chondroitin supplements in slowing or arresting progression of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and economic evaluation». Health Technol Assess 13 (52): 1–148. PMID 19903416. http://www.hta.ac.uk/execsumm/summ1352.htm.

- ↑ McAlindon T, Formica M, LaValley M, Lehmer M, Kabbara K (November 2004). «Effectiveness of glucosamine for symptoms of knee osteoarthritis: results from an internet-based randomized double-blind controlled trial». Am J Med 117 (9): 643–9. doi:. PMID 15501201.

- ↑ Vlad SC, Lavalley MP, McAlindon TE, Felson DT (2007). «Glucosamine for pain in osteoarthritis: Why do trial results differ?». Arthritis & Rheumatism 56 (7): 2267–77. doi:. PMID 17599746.

- ↑ Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G και άλλοι. (February 2008). «OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines». Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16 (2): 137–62. doi:. PMID 18279766. http://www.oarsi.org/pdfs/part_II_OARSI_recommendations_for_management_of_hipknee_OA_2007.pdf.

- ↑ «WHO Disease and injury country estimates». World Health Organization. 2009. Ανακτήθηκε στις Nov. 11, 2009. Ελέγξτε τις τιμές ημερομηνίας στο:

|accessdate=(βοήθεια) - ↑ Green GA (2001). «Understanding NSAIDs: from aspirin to COX-2». Clin Cornerstone 3 (5): 50–60. doi:. PMID 11464731.

- ↑ Hospitalizations for Osteoarthritis Rising Sharply Newswise, Retrieved on September 4, 2008.

- ↑ The global burden of disease : 2004 update.. [Online-Ausg.] ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. ISBN 9789241563710. p. 35.

- ↑ Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 337-363.

- ↑ Civjan, Natanya (2012). Chemical Biology: Approaches to Drug Discovery and Development to Targeting Disease. John Wiley & Sons. σελ. 313. ISBN 9781118437674.

- ↑ Bruyère, O; Burlet, N; Delmas, PD; Rizzoli, R; Cooper, C; Reginster, JY (16 December 2008). «Evaluation of symptomatic slow-acting drugs in osteoarthritis using the GRADE system.». BMC musculoskeletal disorders 9: 165. PMID 19087296.

External links

- American College of Rheumatology Factsheet on OA

- Osteoarthritis The Arthritis Foundation

Πρότυπο:Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue