Ιαπωνική γλώσσα: Διαφορά μεταξύ των αναθεωρήσεων

μ αφαιρέθηκε η Κατηγορία:Ιαπωνία (με το HotCat) |

Χωρίς σύνοψη επεξεργασίας |

||

| Γραμμή 40: | Γραμμή 40: | ||

== Ταξινόμηση == |

== Ταξινόμηση == |

||

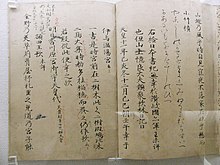

[[File:Genryaku_Manyosyu.JPG|σύνδεσμος=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Genryaku_Manyosyu.JPG|εναλλ.=Page from the Man'yōshū|μικρογραφία|Σελίδα από το [[Μαν γιοσού]], την παλαιότερη ανθολογία της κλασικής ιαπωνικής ποίησης]] |

|||

[[File:Genji_emaki_01003_001.jpg|σύνδεσμος=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Genji_emaki_01003_001.jpg|εναλλ.=Two pages from Genji Monogatari emaki scroll|μικρογραφία|Σελίδας από την [[Ιστορία του Γκέντζι]], από τα σημαντικότερα λογοτεχνικά κείμενα της ιαπωνικής αλλά και παγκόσμιας λογοτεχνίας, 11ος αιώνας]] |

|||

[[File:Japanese_dialects-en.png|σύνδεσμος=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_dialects-en.png|μικρογραφία|Γεωγραφική κατανομή της ιαπωνικής γλώσσας με τις διάφορες διαλέκτους της]] |

|||

[[File:Nihongo_ichiran_01-converted.svg|σύνδεσμος=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nihongo_ichiran_01-converted.svg|μικρογραφία|Πίνακας των χαρακτήρων [[Κάνα]], με τα [[Χιραγκάνα]] στην κορυφή, τα [[Κατακάνα]] στο κέντρο, και τις εκλατινισμένες μορφές τους στην κάτω πλευρά]] |

|||

Οι [[Ιστορική γλωσσολογία|ιστορικοί γλωσσολόγοι]] που εξειδικεύονται στην Ιαπωνική συμφωνούν ότι είναι ένα από τα δύο μέλη της Ιαπωνικής [[γλωσσική οικογένεια|γλωσσικής οικογένειας]]. Το άλλο μέλος είναι η [[Ριουκιουάν γλώσσα]]. (Μια παλαιότερη άποψή, την οποία ασπάζονται αρκετοί μη γλωσσολόγοι, είναι ότι η Ιαπωνική είναι [[απομονωμένη γλώσσα]], της οποίας οι Ριουκιουάν γλώσσες είναι [[διάλεκτος|διάλεκτοι]].) |

Οι [[Ιστορική γλωσσολογία|ιστορικοί γλωσσολόγοι]] που εξειδικεύονται στην Ιαπωνική συμφωνούν ότι είναι ένα από τα δύο μέλη της Ιαπωνικής [[γλωσσική οικογένεια|γλωσσικής οικογένειας]]. Το άλλο μέλος είναι η [[Ριουκιουάν γλώσσα]]. (Μια παλαιότερη άποψή, την οποία ασπάζονται αρκετοί μη γλωσσολόγοι, είναι ότι η Ιαπωνική είναι [[απομονωμένη γλώσσα]], της οποίας οι Ριουκιουάν γλώσσες είναι [[διάλεκτος|διάλεκτοι]].) |

||

| Γραμμή 53: | Γραμμή 56: | ||

Η στερεότυπη Ιαπωνική μπορεί επίσης να διαιρεθεί σε (文語, ''bungo'') ή "λογοτεχνική γλώσσα" και η (口語, ''kōgo'') ή "προφορική γλώσσα", που έχει διαφορετικούς κανόνες [[γραμματική]]ς και διαφορές στο [[λεξιλόγιο]]. Η ''Bungo'' μέθοδος ήταν ο κύριος τρόπος γραφής των Ιαπωνικών έως τα τέλη της δεκαετίας 1940, και χρησιμοποιείται ακόμη από [[Ιστορία|ιστορικούς]], [[Φιλόλογος|φιλολόγους]] και [[νομική|νομικούς]] (αρκετοί ιαπωνικοί [[νόμος|νόμοι]] που επεβίωσαν του [[Β' Παγκόσμιος Πόλεμος|Β' Π.Π.]] είναι ακόμη γραμμένοι σε ''bungo'', αν και γίνονται συνεχείς προσπάθειες εκσυγχρονισμού της γλώσσας). Κυρίαρχος τρόπος ομιλίας και γραφής στην Ιαπωνία σήμερα είναι η ''Kōgo'' μέθοδος, αν και η ''bungo'' γραμματική και λεξιλόγιο χρησιμοποιούνται συχνά για εντυπωσιασμό στη σύγχρονη Ιαπωνική. |

Η στερεότυπη Ιαπωνική μπορεί επίσης να διαιρεθεί σε (文語, ''bungo'') ή "λογοτεχνική γλώσσα" και η (口語, ''kōgo'') ή "προφορική γλώσσα", που έχει διαφορετικούς κανόνες [[γραμματική]]ς και διαφορές στο [[λεξιλόγιο]]. Η ''Bungo'' μέθοδος ήταν ο κύριος τρόπος γραφής των Ιαπωνικών έως τα τέλη της δεκαετίας 1940, και χρησιμοποιείται ακόμη από [[Ιστορία|ιστορικούς]], [[Φιλόλογος|φιλολόγους]] και [[νομική|νομικούς]] (αρκετοί ιαπωνικοί [[νόμος|νόμοι]] που επεβίωσαν του [[Β' Παγκόσμιος Πόλεμος|Β' Π.Π.]] είναι ακόμη γραμμένοι σε ''bungo'', αν και γίνονται συνεχείς προσπάθειες εκσυγχρονισμού της γλώσσας). Κυρίαρχος τρόπος ομιλίας και γραφής στην Ιαπωνία σήμερα είναι η ''Kōgo'' μέθοδος, αν και η ''bungo'' γραμματική και λεξιλόγιο χρησιμοποιούνται συχνά για εντυπωσιασμό στη σύγχρονη Ιαπωνική. |

||

<!-- |

|||

=== Διάλεκτοι === |

|||

:''βλ. κύριο άρθρο [[Ιαπωνικές διάλεκτοι]]'' |

|||

Στην Ιαπωνία ομιλούνται δεκάδες διάλεκτοι, κάτι που ανάγεται σε πολλούς παράγοντες, συμπεριλαμβανομένων της μακράς ανθρώπινης παρουσίας στο ιαπωνικό αρχιπέλαγος, του ορεινού αναγλύφου της χώρας και της μακράς της ιστορικά απομόνωσης - εσωτερικής και εξωτερικής. Τυπικά οι διάλεκτοι διαφέρουν στον τρόπο τονισμού, στη γραμματική, το λεξιλόγιο και στη χρήση των μορίων. Λίγες διαθέτουν και διαφοροποιημένες δεξαμενές φωνηέντων και συμφώνων. |

|||

Δεκάδες διάλεκτοι ομιλούνται στην Ιαπωνία. The profusion is due to many factors, including the length of time the archipelago has been inhabited, its mountainous island terrain, and Japan's long history of both external and internal isolation. Dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional [[morphology (linguistics)|morphology]], [[vocabulary]], and particle usage. Some even differ in [[vowel]] and [[consonant]] inventories, although this is uncommon. |

|||

The main distinction in Japanese dialects is between Tokyo-type (東京式, ''Tōkyō-shiki'') and Western-type (京阪式, ''Keihan-shiki''), though Kyushu-type dialects form a smaller third group. Within each type are several subdivisions. The Western-type dialects are actually in the central region, with borders roughly formed by [[Toyama Prefecture|Toyama]], [[Kyoto Prefecture|Kyōto]], [[Hyogo Prefecture|Hyōgo]], and [[Mie Prefecture|Mie]] Prefectures; most [[Shikoku]] dialects are also Western-type. Dialects further west are actually of the Tokyo type. The final category of dialects are those that are descended from the Eastern dialect of [[Old Japanese]]; these dialects are spoken in [[Hachijojima]], [[Tosa Province|Tosa]], and a very few other locations. |

|||

Dialects from peripheral regions, such as [[Tōhoku Region|Tōhoku]] or [[Tsushima]], may be unintelligible to speakers from other parts of the country. The several dialects used in [[Kagoshima]] in southern [[Kyūshū]] are famous for being unintelligible not only to speakers of standard Japanese but to speakers of nearby dialects elsewhere in Kyūshū as well, probably due in part to the Kagoshima dialects' peculiarities of pronunciation, which include the existence of closed syllables (i.e., syllables that end in a consonant, such as {{IPA|/kob/}} or {{IPA|/koʔ/}} for Standard Japanese {{IPA|/kumo/}} "spider"). The vocabulary of Kagoshima dialect is 84% cognate with standard Tokyo dialect. [[Kansai-ben]], a group of dialects from west-central Japan, is spoken by many Japanese; the Osaka dialect in particular is associated with comedy. |

|||

The [[Ryukyuan languages]], while closely related to Japanese, are distinct enough to be considered a separate branch of the [[Japonic languages|Japonic]] family, and are not dialects of Japanese. They are spoken in the [[Ryukyu Islands]] and in some islands that are politically part of [[Kagoshima Prefecture]]. Not only is each language unintelligible to Japanese speakers, but most are unintelligible to those who speak other Ryukyuan languages. |

|||

Recently, Standard Japanese has become prevalent nationwide, due not only to [[television]] and [[radio]], but also to increased mobility within Japan due to its system of roads, railways, and airports. Young people usually speak their local dialect and the standard language, though in most cases, the local dialect is influenced by the standard, and regional versions of "standard" Japanese have local-dialect influence. |

|||

== Φθόγγοι == |

|||

Τα φωνήεντα της Ιαπωνικής είναι «καθαρά» φωνήεντα, ανάλογα με αυτά της Ελληνικής, της Ισπανικής ή της Ιταλικής. Ξεχωρίζει μόνο το υψηλό οπίσθιο φωνήεν {{IPA|/ɯ/}}, το οποίο ομοιάζει με το {{IPA|/u/}}, αλλά προφέρεται με τα χείλη λιγότερο στρογγυλεμένα. Τα φωνήεντα είναι συνολικά πέντε – όσα και της Ελληνικής – και εμφανίζουν μία βραχεία και μία μακρά μορφή. |

|||

Some Japanese consonants have several [[allophone]]s, which may give the impression of a larger inventory of sounds. However, some of these allophones have since become phonemic. For example, in the Japanese up to and including the first half of the twentieth century, the phonemic sequence {{IPA|/ti/}} was [[palatalization|palatalized]] and realized phonetically as {{IPA|[tɕi]}}, approximately ''chi''; however, now {{IPA|/ti/}} and {{IPA|/tɕi/}} are distinct, as evidenced by words like ''paatii'' {{IPA|[paatii]}} "party" and ''chi'' {{IPA|[tɕi]}} "ground." |

|||

The syllabic structure and the [[phonotactics]] are very simple: the only [[consonant cluster]]s allowed within a syllable consist of one of a subset of the consonants plus /j/. This type of clusters only occurs in onsets. However, consonant clusters across syllables are allowed as long as the two consonants are a nasal followed a homo-organic consonant. The consonant length (geminates) is also phonemic. |

|||

== Grammar == |

|||

{{main|Japanese grammar}} |

|||

=== Sentence structure === |

|||

The basic Japanese word order is [[Subject Object Verb]]. Subject, Object, and other grammatical relations are usually marked by [[Japanese particles|particles]], which are suffixed to the words that they modify, and are thus properly called [[postposition]]s. |

|||

The basic sentence structure is [[topic-comment]]. For example, ''Kochira-wa Tanaka-san desu.'' ''Kochira'' ("this") is the topic of the sentence, indicated by the particle ''-wa''. The verb is ''desu'', a [[copula]], commonly translated as "to be" (though there are other verbs that can be translated as "to be"). As a phrase, ''Tanaka-san desu'' is the comment. This sentence loosely translates to "As for this person, (it) is Mr./Mrs./Ms. Tanaka". Thus Japanese, like [[Chinese language|Chinese]], [[Korean language|Korean]], and many other Asian languages, is often called a [[topic-prominent language]], which means it has a strong tendency to indicate the topic separately from the subject, and the two do not always coincide. The sentence ''Zō-wa hana-ga nagai (desu)'' literally means, "As for elephants, (their) noses are long". The topic is ''zō'' "elephant", and the subject is ''hana'' "nose". |

|||

Japanese is a [[pro-drop language]], meaning that the subject or object of a sentence need not be stated if it is obvious from context. In addition, it is commonly felt that the shorter a Japanese sentence is, the better (a quality called "[[Iki (aesthetic ideal)|iki]]" in Japanese). As a result of this grammatical permissiveness and tendency towards brevity, Japanese speakers tend naturally to omit words from sentences, rather than refer to them with [[pronoun]]s. In the context of the above example, ''hana-ga nagai'' would mean "[their] noses are long," while ''nagai'' by itself would mean "[they] are long." A single verb can be a complete sentence: ''Yatta!'' "[I / we / they / etc] did [it]!". In addition, since adjectives can form the predicate in a Japanese sentence (below), a single adjective can be a complete sentence: ''Urayamashii!'' "[I'm] jealous [of it]!". |

|||

While the language has some words that are translated as pronouns, these are not used as frequently as pronouns in some [[Indo-European language]]s, and function differently. Instead, Japanese typically relies on special verb forms and auxiliary verbs to indicate the "direction" of an action: "down" to the speaker or persons related to the speaker, or "up" to the listener or other person. For example, ''setsumei shite moratta'' (literally, "[I/we] obtained explaining") means "[he/she] explained it to [me/us]". Similarly, ''oshiete ageta'' (literally, "teach-handed up") is commonly used to mean "[I/we] told [him/her]". Such "directional" auxiliary verbs thus serve a function comparable to that of pronouns and prepositions in Indo-European languages to indicate the actor and the recipient of an action. |

|||

Japanese "pronouns" also function differently from Indo-European pronouns (and more like nouns) in that they can take modifiers as any other noun may. For instance, you cannot say in English: |

|||

: *The big he ran down the street. (ungrammatical) |

|||

But you ''can'' grammatically say essentially the same thing in Japanese: |

|||

: ''Ōkii kare-wa michi-o hashitte itta.'' (grammatically correct) |

|||

This is partly due to the fact that these words evolved from regular nouns, such as ''kimi'' "you" (君 "lord"), ''anata'' "you" (貴方 "that side, yonder"), and ''boku'' "I" (僕 "servant"). This is why some linguists do not classify Japanese "pronouns" as pronouns, but rather as referential nouns. Japanese personal pronouns are generally used only in situations requiring special emphasis as to who is doing what to whom. |

|||

The choice of words used as pronouns is correlated with the sex of the speaker and the social situation in which they are spoken: men and women alike in a formal situation generally refer to themselves as ''watashi'' or ''watakushi'', while men in rougher or intimate conversation are much more likely to use the word ''ore'' or ''boku''. Similarly, different words such as ''anata'', ''kimi'', and ''omae'' may be used to refer to a listener depending on the listener's relative social position and the degree of familiarity between the speaker and the listener. |

|||

Japanese often use titles of the person referred to where pronouns would be used in English. For example, when speaking to one's teacher, it is appropriate to use ''sensei'' (先生, teacher), but inappropriate to use ''anata''. This is because ''anata'' is used to refer to people of equal or lower status, and one's teacher has higher status. |

|||

It is very common for English speakers to include ''watashi-wa'' or ''anata-wa'' at the beginning of every Japanese sentence. Though these sentences are grammatically correct, they sound terribly strange even in very formal situations. It is roughly the equivalent of using a noun over and over in English, when a pronoun would suffice "John is coming over, so make sure you fix John a sandwich, because John loves sandwiches. I hope John likes the dress I'm wearing..." |

|||

=== Inflection and conjugation === |

|||

Japanese nouns have neither number nor gender. Thus ''hon'' may mean "book" or "books". It is possible to explicitly indicate more than one, either by providing a quantity (often with a [[Japanese counter word|counter word]]) or by adding a suffix (which is rare). Words for people are usually understood as singular. Thus ''Tanaka-san'' usually means ''Mr./Ms. Tanaka''. Words that refer to people and animals can be made to indicate a group of individuals through the addition of a collective suffix (a noun suffix that indicates a group), such as ''-tachi''. Though some words, like ''hitobito'' "people", always refer to more than one, Japanese nouns without such additions are neither singular nor plural. ''Hito'' (人) could mean "person" or "people", ''ki'' (木) could be "tree" or "trees" without any implied preference for singular or plural. |

|||

Verbs are [[Japanese verb conjugations|conjugated]] to show tenses, of which there are two: past and present, or non-past, which is used for the present and the future. For verbs that represent an ongoing process, the ''-te iru'' form indicates a continuous (or progressive) tense. For others that represent a change of state, the ''-te iru'' form indicates a perfect tense. For example, ''kite iru'' means "He has come (and is still here)", but ''tabete iru'' means "He is eating". |

|||

Questions (both with an interrogative pronoun and yes/no questions) have the same structure as affirmative sentences, but with intonation rising at the end. In the formal register, the question particle ''-ka'' is added. For example, ''Ii desu'' "It is OK" becomes ''Ii desu-ka'' "Is it OK?". In a more informal tone sometimes the particle ''-no'' is added instead to show a personal interest of the speaker: ''Dōshite konai-no?'' "Why aren't (you) coming?". Some simple queries are formed simply by mentioning the topic with an interrogative intonation to call for the hearer's attention: ''Kore-wa?'' "(What about) this?"; ''Namae-wa?'' "(What's your) name?". |

|||

Negatives are formed by inflecting the verb. For example, ''Pan-o taberu'' "I will eat bread" or "I eat bread" becomes ''Pan-o tabenai'' "I will not eat bread" or "I do not eat bread". |

|||

The so-called ''-te'' verb form is used for a variety of purposes: either progressive or perfect aspect (see above); combining verbs in a temporal sequence (''Asagohan-o tabete sugu dekakeru'' "I'll eat breakfast and leave at once"), simple commands, conditional statements and permissions (''Dekakete-mo ii?'' "May I go out?"), etc. |

|||

The word ''da'' (plain), ''desu'' (polite) is the [[copula]] verb. It corresponds approximately to the English ''be'', but often takes on other roles. Two additional common verbs are used to indicate existence ("there is") or, in some contexts, property: ''aru'' (negative ''nai'') and ''iru'' (negative ''inai''), for inanimate and animate things, respectively. For example, ''Neko ga iru'' "There's a cat", ''Ii kangae-ga nai'' "[I] haven't got a good idea". |

|||

The verb "to do" (''suru'', polite form ''shimasu'') is often used to make verbs from nouns (''ai suru'' "to love", ''benkyō suru'' "to study", etc.) and has been productive in creating modern slang words (eg: ''Bushu-o suru'' "to do a Bush" in historical reference to an embarrassing diplomatic faux-pas in 1992 when US President [[George Bush Sr]] inadvertently vomited on the unfortunate Japanese Prime Minister). Japanese also has a huge number of compound verbs to express concepts that are described in English using a verb and a preposition (e.g. ''tobidasu'' "to fly out, to flee," from ''tobu'' "to fly, to jump" + ''dasu'' "to put out, to emit"). |

|||

There are three types of [[Japanese adjectives|adjective]] (see also [[Japanese adjectives]]): |

|||

# ''keiyōshi'', or ''i'' adjectives, which have a [[Japanese verb conjugations|conjugating]] ending ''i'' (such as ''atsui'', "to be hot") which can become past (''atsukatta'' - "it was hot"), or negative (''atsuku nai'' - "it is not hot"). Note that ''nai'' is also an ''i'' adjective, which can become past (''atsuku nakatta'' - it was not hot). |

|||

#: ''atsui hi'' "a hot day". |

|||

# ''keiyōdōshi'', or ''na'' adjectives, which are followed by a form of the [[copula]], usually ''na''. For example ''hen'' (strange) |

|||

#: ''hen na hito'' "a strange person". |

|||

# ''rentaishi'', also called true adjectives, such as ''onaji'' "the same" |

|||

#: ''onaji hi'' "the same day". |

|||

Both ''keiyōshi'' and ''keiyōdōshi'' may [[predicate]] sentences. For example, |

|||

: ''Gohan-ga atsui.'' "The rice is hot." |

|||

: ''Kare-wa hen da.'' "He's strange." |

|||

Both inflect, though they do not show the full range of conjugation found in true verbs. |

|||

The ''rentaishi'' in Modern Japanese are few in number, and unlike the other words, are limited to directly modifying nouns. They never predicate sentences. Examples include ''ookina'' "big" and ''onaji'' "the same" (although there is also a noun ''onaji'' that can be followed by ''da'', as in ''onaji da''). |

|||

Both ''keiyōdōshi'' and ''keiyōshi'' form [[adverb]]s, by following with ''ni'' in the case of ''keiyōdōshi'': |

|||

: ''hen ni naru'' "become strange", |

|||

and by changing ''i'' to ''ku'' in the case of ''keiyōshi'': |

|||

: ''atsuku naru'' "become hot". |

|||

The grammatical function of nouns is indicated by [[postposition]]s, also called [[Japanese particles|particles]]. These include for example: |

|||

* '''''no''''' for possession, or nominalizing phrases. |

|||

: ''Watashi '''no''' kamera'' "My camera" / ''Sukii-ni iku '''no''' ga suki desu'' "(I) like going skiing." |

|||

* '''''ga''''' for subject. |

|||

: ''Kare '''ga''' yatta.'' "He did it." |

|||

* '''''o''''' for direct object |

|||

: ''Nani '''o''' tabemasu ka?'' "What will (you) eat?" |

|||

* '''''ni''''' for indirect object. |

|||

: ''Tanaka-san '''ni''' kiite kudasai'' "Please ask Mr./Ms. Tanaka". |

|||

* '''''wa''''' for the topic. |

|||

: ''Watashi '''wa''' tai ryōri-ga ii desu.'' "As for me, Thai food is good." <small>(Note that English generally makes no distinction between sentence topic and subject.)</small> |

|||

=== Politeness === |

|||

{{main|Japanese honorifics|Japanese titles}} |

|||

Unlike most western languages, Japanese has an extensive grammatical system to express politeness and formality. |

|||

Broadly speaking, there are three main politeness levels in spoken Japanese: the '''plain form''' (''kudaketa'' 砕けた or ''futsuu'' 普通), the '''simple polite form''' (''teineigo'' 丁寧語) and the '''advanced polite form''' (''[[keigo]]'' 敬語). |

|||

Since most relationships are not equal in Japanese [[society]], one person typically has a higher position. This position is determined by a variety of factors including job, age, experience, or even psychological state (e.g., a person asking a favour tends to do so politely). The person in the lower position is expected to use a polite form of speech, whereas the other might use a more plain form. Strangers will also speak to each other politely. Japanese children rarely use polite speech until they are teens, at which point they are expected to begin speaking in a more adult manner. ''See [[uchi-soto]]'' |

|||

The '''plain form''' in Japanese is recognized by the shorter, dictionary form of verbs, and the ''da'' form of the [[copula]]. At the '''''teinei''''' level, [[verb]]s end with the helping verb ''-masu'', and the copula ''desu'' is used. The advanced polite form, '''''[[keigo]]''''', actually consists of two kinds of politeness: '''honorific''' language (''sonkeigo'') and '''humble''' (''kenjōgo'') language. Whereas ''teineigo'' is an [[inflection|inflectional]] system, ''keigo'' often employs many special (often [[irregular verb|irregular]]) honorific and humble verb forms: ''iku'' "to go" becomes ''ikimasu'' in polite form, but is replaced by ''mairimasu'' in humble form and ''irasshaimasu'' in honorific form. |

|||

The difference between honorific and humble speech is particularly pronounced in the Japanese language. Humble language is used to talk about oneself or one's own group (company, family) whilst honorific language is mostly used when describing the interlocutor and his/her group. For example, the ''-san'' suffix ("Mr" or "Ms") is an example of honorific language. It is not used to talk about oneself or when talking about someone from one's company to an external person, since the company is the speaker's "group". When speaking directly to one's superior in one's company or when speaking with other employees within one's company about a superior, a Japanese person will use vocabulary and inflections of the honorific register to refer to the in-group superior and his or her speech and actions. When speaking to a person from another company (i.e., a member of an out-group), however, a Japanese person will use the plain or the humble register to refer to the speech and actions of his or her own in-group superiors. In short, the register used in Japanese to refer to the person, speech, or actions of any particular individual varies depending on the relationship (either in-group or out-group) between the speaker and listener, as well as depending on the relative status of the speaker, listener, and third-person referents. For this reason, the Japanese system for explicit indication of social register is known as a system of "relative honorifics." This stands in stark contrast to the [[Korean language|Korean]] system of "absolute honorifics," in which the same register is used to refer to a particular individual (e.g. one's father, one's company president, etc.) in any context regardless of the relationship between the speaker and interlocutor. Thus, polite Korean speech can sound very presumptuous when translated verbatim into Japanese, as in Korean it is acceptable and normal to say things like "Our '''Mr.''' Company-President..." when communicating with a member of an out-group, which would be very inappropriate in a Japanese social context. |

|||

Most [[noun]]s in the Japanese language may be made polite by the addition of ''o-'' or ''go-''; as a prefix. ''o-'' is generally used for words of native Japanese origin, whereas ''go-'' is affixed to words of Chinese derivation. In some cases, the prefix has become a fixed part of the word, and is included even in regular speech, such as ''gohan'' 'cooked rice; meal.' Such a construction often indicates deference to either the item's owner or to the object itself. For example, the word ''tomodachi'' 'friend,' would become ''o-tomodachi'' when referring to the friend of someone of higher status (though mothers often use this form to refer to their children's friends). On the other hand, a polite female speaker may sometimes refer to ''mizu'' 'water' as ''o-mizu'' merely to show politeness; this contrasts with the more abrupt speech of rude men (though men may also use very polite forms when speaking to superiors). ''See [[Gender differences in spoken Japanese]]''. |

|||

Most Japanese people employ politeness to indicate a lack of familiarity. That is, they use polite forms for new acquaintances, but if a relationship becomes more intimate, they no longer use them. This occurs regardless of age, social class, or gender. |

|||

Many researchers report that since the [[1990s]], the use of polite forms has become rarer. Needless to say, many older people disapprove of this trend. Young people usually receive extensive training in the "proper" use of polite language when they start to work for a company. |

|||

== Vocabulary == |

|||

The original language of Japan, or at least the original language of a certain population that was ancestral to a significant portion of the historical and present Japanese nation, was the so-called ''yamato kotoba'' (大和言葉 or 大和詞, i.e. "[[Yamato period|Yamato]] words"), which in scholarly contexts is sometimes referred to as ''wa-go'' (倭語 or 和語, i.e. the "[[Wa]] language"). In addition to words from this original language, present-day Japanese includes a great number of words that were either borrowed from [[Chinese language|Chinese]] or constructed from Chinese roots following Chinese patterns. These words, known as ''[[Sino-Japanese|kango]]'', entered the language from the fifth century onwards via contact with Chinese culture, both directly and through Korea. According to some estimates, Chinese-based words comprise as much as seventy percent of the total vocabulary of the modern Japanese language and form as much as thirty to forty percent of words used in speech. |

|||

Like Latin-derived words in English, ''[[Sino-Japanese|kango]]'' words typically are perceived as somewhat formal or academic compared to equivalent Yamato words. Indeed, it is generally fair to say that an English word derived from Latin/French roots typically corresponds to a Sino-Japanese word in Japanese, whereas a simpler Anglo-Saxon word would best be translated by a Yamato equivalent. |

|||

A much smaller number of words (in fact, an almost negligible number) has been borrowed from [[Korean language|Korean]] and [[Ainu language|Ainu]]. Japan has also borrowed a number of words from other languages, particularly ones of European extraction, which are called ''[[gairaigo]]''. This began with [[Japanese words of Portuguese origin|borrowings from Portuguese]] in the [[16th century]], followed by borrowing from Dutch during Japan's [[sakoku|long isolation]] of the [[Edo period]]. With the [[Meiji Restoration]] and the reopening of Japan in the [[19th century]], borrowing occurred from [[German language|German]], [[French language|French]] and [[English language|English]]. Currently, words of English origin are the most commonly borrowed. |

|||

In the Meiji era, the Japanese also coined many neologisms using Chinese roots and morphology to translate Western concepts. The Chinese and Koreans imported many of these pseudo-Chinese words into [[Chinese language|Chinese]], [[Korean language|Korean]], and [[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]] via their [[kanji]] characters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, 政治 ''seiji'' ("politics"), and 化学 ''kagaku'' ("chemistry") are words derived from [[Sinitic]] etyma that were first created and used by the Japanese, and only later borrowed into Chinese and other East Asian languages. As a result, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese share a large common corpus of vocabulary in the same way a large number of Greco-Roman words is shared among modern European languages, although many such academic words formed from Greco-Roman etyma were certainly coined by native speakers of other languages, such as English. |

|||

In the past few decades, ''[[wasei-eigo]]'' (made-in-Japan English) has become a prominent phenomenon. Words such as ''wanpataan'' (< ''one'' + ''pattern'', "to be in a rut", "to have a one-track mind") and ''sukinshippu'' (< ''skin'' + ''-ship'', "physical contact"), although coined by compounding English roots, are nonsensical in a non-Japanese context. A small number of such words have been borrowed back into English. |

|||

Additionally, many native Japanese words have become commonplace in English, due to the popularity of many Japanese cultural exports. Words such as [[sushi]], [[judo]], [[karate]], [[sumo]], [[karaoke]], [[origami]], [[tsunami]], [[samurai]], [[haiku]], [[ninja]], [[sayonara]], [[rickshaw]] (from 人力車 ''jinrikisha''), [[futon]], and many others have become part of the English language. See [[list of English words of Japanese origin]] for more. |

|||

== Writing system == |

|||

{{main|Japanese writing system}} |

|||

Before the [[5th century]], the Japanese had no [[writing]] system of their own. They began to adopt the [[Chinese writing]] script along with many other aspects of [[Culture of China|Chinese culture]] after their introduction by [[Korea]]n monks and scholars during the 5th and 6th centuries AD. |

|||

At first, the Japanese wrote in [[Classical Chinese]], with Japanese names represented by characters used for their sounds and not their meanings. Later, this latter principle was used to write pure Japanese poetry and prose; however, some Japanese words were written with characters for their meaning and not the original Chinese sound. An example of this mixed style is the [[Kojiki]], which was written in 712 AD. They then started to use Chinese characters to write Japanese in a style known as ''man'yōgana'', a syllabic script which used Chinese characters for their sounds in order to transcribe the words of Japanese speech syllable by syllable. |

|||

Over time, a writing system evolved. [[Chinese characters]] ([[kanji]]) were used to write either words borrowed from Chinese, or Japanese words with the same or similar meanings. Chinese characters were also used to write grammatical elements, were simplified, and eventually became two syllabic scripts: [[hiragana]] and [[katakana]]. |

|||

Modern Japanese is written in a mixture of three main systems: [[kanji]], characters of Chinese origin used to represent both Chinese [[loanword]]s into Japanese and a number of native Japanese [[morpheme]]s; and two [[syllabary|syllabaries]]: [[hiragana]] and [[katakana]]. The [[Latin alphabet]] is also sometimes used. Arabic numerals are much more common than the kanji characters when used in counting, but kanji numerals are still used in compounds, such as 統一 ''tōitsu'' "unification." |

|||

Hiragana are used for words without kanji representation, for words no longer written in kanji, and also following kanji to show conjugational endings. Because of the way verbs (and adjectives) in Japanese are [[conjugated]], kanji alone cannot fully convey Japanese tense and mood, as kanji cannot be subject to variation when written without losing its meaning. For this reason, hiragana are suffixed to the ends of kanji to show verb and adjective conjugations. Hiragana used in this way are called [[okurigana]]. Hiragana are also written in a superscript called [[furigana]] above or beside a kanji to show the proper reading. This is done to facilitate learning, as well as to clarify particularly old or obscure (or sometimes invented) readings. |

|||

Katakana, like hiragana, are a syllabary; katakana are primarily used to write foreign words, plant and animal names, and for emphasis. For example "Australia" has been adapted as ''Ōsutoraria'', and "supermarket" has been adapted and shortened into ''sūpā''. [[romaji|''Rōmaji'']], literally "Roman letters," is the Japanese term for the [[Latin alphabet]]. ''Rōmaji'' are used for some loan words like "CD", "DVD", etc., and also for some Japanese creations like "Sony." |

|||

Japanese students begin to learn kanji characters from their first year at elementary school. A guideline created by the Japanese Ministry of Education, the list of [[kyōiku kanji]], specifies the 1,006 simple characters a child is to learn by the end of sixth grade. Children continue to study another 939 characters in junior high school, covering in total 1,945 ''[[jōyō kanji]]'' ("common use kanji") characters, which is generally considered sufficient for everyday life, although many kanji used in everyday life are not included in the list. An appendix of 290 additional characters for names was decreed in 1951. Various semi-official bodies were set up to monitor and enforce restrictions on the use of kanji in the press, publishing, in television broadcasts, etc. Thereafter, the official list of [[kyōiku kanji]] was repeatedly revised, but the total number of officially sanctioned characters remained largely unchanged. |

|||

A different list of officially approved kanji is used for purposes of registering personal names. Names containing unapproved characters are denied registration. However, as with the list of [[kyōiku kanji]], criteria for inclusion were often arbitrary and led to many common and popular characters being disapproved for use. Under popular pressure and following a court decision holding the exclusion of common characters unlawful, the list of "approved" characters was substantially extended. Furthermore, families whose names are not on these lists were permitted to continue using the older forms. |

|||

Historically, attempts to limit the number of kanji in use commenced in the mid-19th century, but did not become a matter of government intervention until after Japan's defeat in the Second World War. During the period of post-war occupation (and influenced by the views of some U.S. officials), various schemes including the complete abolition of kanji and exclusive use of rōmaji were considered. The [[kyōiku kanji]] scheme arose as a compromise solution. |

|||

== Learning Japanese == |

|||

Many major universities throughout the world provide Japanese language courses, and a number of secondary and even primary schools worldwide offer courses in the language. International interest in the Japanese language dates to the 1800s but has become more prevalent following Japan's economic bubble of the 1980s and the global popularity of Japanese pop culture in the 1990s and beyond. About 2.3 million people studied the language worldwide in [[2003]]: 900,000 South Koreans, 389,000 [[People's Republic of China|Chinese]], 381,000 Australians, and 140,000 Americans study Japanese in lower and higher educational institutions. In Japan, more than 90,000 foreign students study at [[List of universities in Japan|Japanese universities]] and Japanese [[language school]]s, including 77,000 Chinese and 15,000 South Koreans in 2003. Furthermore, local governments and some [[NPO]] groups provide free Japanese language classes for foreign residents, including [[Japanese Brazilians]] and foreigners married to Japanese nationals. |

|||

The Japanese government provides standard tests to measure spoken and written comprehension of Japanese for second language learners; the most prominent is the [[Japanese Language Proficiency Test]] (JLPT). The Japanese External Trade Organization [[JETRO]] organizes the ''Business Japanese Proficiency Test'', to test ability to understand Japanese in a business setting. |

|||

--> |

|||

== Βλέπε επίσης == |

== Βλέπε επίσης == |

||

* [[Ιαπωνικός πολιτισμός]] |

|||

* [[Ιαπωνική γλώσσα και υπολογιστές]] |

|||

* [[Ιαπωνική λογοτεχνία]] |

|||

* [[Ιαπωνικά ονόματα]] |

|||

* [[Ιαπωνική γραφή]] |

* [[Ιαπωνική γραφή]] |

||

* [[Λατινισμός Χέπμπορν]] |

* [[Λατινισμός Χέπμπορν]] |

||

Έκδοση από την 19:17, 12 Ιουνίου 2016

| Ιαπωνικά | |

|---|---|

| 日本語 | |

| Ταξινόμηση | Ιαπωνικές γλώσσες |

| Σύστημα γραφής | κάντζι, Κάνα, Κατακάνα και Χιραγκάνα |

| Κατάσταση | |

| Επίσημη γλώσσα | De facto στην |

| ISO 639-1 | ja |

| ISO 639-2 | jpn |

| ISO 639-3 | jpn |

| SIL | - |

Η Ιαπωνική (日本語, Nihongo) είναι γλώσσα που ομιλείται από 127 εκατ. ανθρώπους, κυρίως στην Ιαπωνία, αλλά και σε κοινότητες Ιαπώνων μεταναστών σε όλο τον κόσμο. Θεωρείται συγκολλητική γλώσσα και διακρίνεται για το σύνθετο πλέγμα εκφράσεων ευγενείας που απεικονίζουν την ιεραρχική φύση της ιαπωνικής κοινωνίας, με ρηματικούς τύπους και ιδιαίτερο λεξιλόγιο που υποδεικνύει τη σχετική θέση (status) του ομιλητή και του ακροατή. Η δεξαμενή ήχων της Ιαπωνικής είναι σχετικά μικρή και διαθέτει ένα λεξικογραφικά διακριτό σύστημα τόνων (έντασης φωνής). Το ιστορικό αρχείο της γλώσσας ανάγεται στον 8ο αιώνα, όταν συντέθηκαν τα τρία μείζονα έργα της αρχαίας ιαπωνικής.

Η Ιαπωνική γράφεται με συνδυασμό τριών διαφορετικών τύπων χαρακτήρων: Οι κινεζικοί χαρακτήρες (ονομάζονται Κάντζι), ενώ οι δύο συλλαβικές γραφές, χιραγκάνα και κατακάνα. Το λατινικό αλφάβητο (που αποκαλείται ρομάτζι) χρησιμοποιείται συχνά στη σύγχρονη Ιαπωνική, για ονόματα εταιρειών, διαφημιστικούς λόγους ή υπολογιστική χρήση. Η αραβική αρίθμηση χρησιμοποιείται εν γένει, αλλά επίσης κοινός τόπος είναι η παραδοσιακή Κινεζική/Ιαπωνική αρίθμηση.

Το ιαπωνικό λεξιλόγιο έχει επηρεαστεί ιδιαίτερα από δάνεια άλλων γλωσσών. Μεγάλος αριθμός λέξεων προέρχονται από την Κινεζική ή δημιουργήθηκαν βάσει κινεζικών προτύπων, σε μια περίοδο 1.500 τουλάχιστον χρόνων. Από τα τέλη του 19ου αιώνα, η Ιαπωνική δανείστηκε αρκετά μεγάλο αριθμό λέξεων, κυρίως αγγλικών.

Ταξινόμηση

Οι ιστορικοί γλωσσολόγοι που εξειδικεύονται στην Ιαπωνική συμφωνούν ότι είναι ένα από τα δύο μέλη της Ιαπωνικής γλωσσικής οικογένειας. Το άλλο μέλος είναι η Ριουκιουάν γλώσσα. (Μια παλαιότερη άποψή, την οποία ασπάζονται αρκετοί μη γλωσσολόγοι, είναι ότι η Ιαπωνική είναι απομονωμένη γλώσσα, της οποίας οι Ριουκιουάν γλώσσες είναι διάλεκτοι.)

Η γενετική συγγένεια της Ιαπωνικής οικογένειας είναι αβέβαιη. Έχουν προταθεί διάφορες θεωρίες, που τη συνδέουν με μια ποικιλία άλλων γλωσσών και οικογενειών, ανάμεσα στις οποίες περιλαμβάνονται εξαφανισμένες γλώσσες που ομιλούντο από ιστορικούς πολιτισμούς της κορεατικής χερσονήσου, οι Αλταϊκές και οι Αυστρονησιακές. Συχνά προτάθηκε ως κρεολή γλώσσα, καθώς συνδυάζει στοιχεία από αρκετές γλώσσες. Οι διάφορες θεωρίες που έχουν προταθεί εκτίθενται λεπτομερειακά στο άρθρο σχετικά με τις ταξινομήσεις της Ιαπωνικής γλώσσας. Έως τώρα, καμία θεωρία δεν είναι γενικώς αποδεκτή ως ορθή και το θέμα πιθανώς θα παραμείνει υπό αμφισβήτηση και στο μέλλον.

Γεωγραφική κατανομή

Αν και η Ιαπωνική ομιλείται σχεδόν αποκλειστικά στην Ιαπωνία, ομιλείτο και ακόμα ομιλείται ενίοτε και αλλού. Όταν η Ιαπωνία κατέλαβε την Κορέα, την Ταϊβάν, τμήμα της κινεζικής ηπειρωτικής γης και διάφορες νήσους του Ειρηνικού, γηγενείς πληθυσμοί εξαναγκάστηκαν να μάθουν την Ιαπωνική ως τμήμα της πολιτικής διαμόρφωσης της αυτοκρατορίας. Το αποτέλεσμα είναι ότι ακόμη και σήμερα στις συγκεκριμένες χώρες πολλοί μιλούν την Ιαπωνική αντί των τοπικών γλωσσών. Οι κοινότητες Ιαπώνων μεταναστών, (ιδίως αυτή της Βραζιλίας), χρησιμοποιούν την Ιαπωνική ως πρωταρχική τους γλώσσα. Ιάπωνες μετανάστες υπάρχουν επίσης στο Περού, την Αυστραλία (ειδικά το Σίδνεϊ, το Μπρισμπέιν και τη Μελβούρνη) και στις Η.Π.Α. (ιδιαίτερα την Καλιφόρνια και τη Χαβάη). Υπάρχει επίσης μια μικρή κοινότητα μεταναστών στο Νταβάο και τις Φιλιππίνες. Οι απόγονοί τους (γνωστοί ως nikkei 日系, κυριολεκτικά ιαπωνικής καταγωγής), ωστόσο, σπάνια τη μιλούν με ευχέρεια. Εκτιμάται ότι αρκετά εκατομμύρια μη Ιάπωνες μελετούν τη γλώσσα, ενώ τη διδάσκουν πολλά σχολεία της πρωτοβάθμιας και της δευτεροβάθμιας εκπαίδευσης.

Επίσημη κατάσταση

Η Ιαπωνική είναι η επίσημη γλώσσα της Ιαπωνίας. Υπάρχουν δύο μορφές της γλώσσας που θεωρούνται στερεότυπες: (標準語, hyōjungo) ή στερεότυπη Ιαπωνική και (共通語, kyōtsūgo) ή κοινή γλώσσα. Η επίσημη πολιτική για εκσυγχρονισμό της γλώσσας έχει αμβλύνει τις διαφορές ανάμεσα στις δύο. Η Hyōjungo εκδοχή, η οποία συζητείται στο παρόν λήμμα, διδάσκεται στα σχολεία και χρησιμοποιείται στην τηλεόραση και τις επίσημες επικοινωνίες.

Η στερεότυπη Ιαπωνική μπορεί επίσης να διαιρεθεί σε (文語, bungo) ή "λογοτεχνική γλώσσα" και η (口語, kōgo) ή "προφορική γλώσσα", που έχει διαφορετικούς κανόνες γραμματικής και διαφορές στο λεξιλόγιο. Η Bungo μέθοδος ήταν ο κύριος τρόπος γραφής των Ιαπωνικών έως τα τέλη της δεκαετίας 1940, και χρησιμοποιείται ακόμη από ιστορικούς, φιλολόγους και νομικούς (αρκετοί ιαπωνικοί νόμοι που επεβίωσαν του Β' Π.Π. είναι ακόμη γραμμένοι σε bungo, αν και γίνονται συνεχείς προσπάθειες εκσυγχρονισμού της γλώσσας). Κυρίαρχος τρόπος ομιλίας και γραφής στην Ιαπωνία σήμερα είναι η Kōgo μέθοδος, αν και η bungo γραμματική και λεξιλόγιο χρησιμοποιούνται συχνά για εντυπωσιασμό στη σύγχρονη Ιαπωνική.

Βλέπε επίσης

Δικτυακοί τόποι

- Η αναφορά του Εθνολόγου για τον κώδικα JPN

- Ορισμοί των διαφορετικών ιαπωνικών διαλέκτων

- A page dealing with the Kansai dialect of Japanese

Βιβλιογραφία

- Bloch, Bernard. (1946). Studies in colloquial Japanese I: Inflection. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 66, 97-109.

- Bloch, Bernard. (1946). Studies in colloquial Japanese II: Syntax. Language, 22, 200-248.

- Chafe, William L. (1976). Giveness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In C. Li (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 25–56). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-447350-4.

- Kuno, Susumu. (1973). The structure of the Japanese language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-11049-0.

- Kuno, Susumu. (1976). Subject, theme, and the speaker's empathy: A re-examination of relativization phenomena. In Charles N. Li (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 417–444). New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-447350-4.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1975). A reference grammar of Japanese. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01813-4.

- McClain, Yoko Matsuoka. (1981). Handbook of modern Japanese grammar: 口語日本文法便覧 [Kōgo Nihon bumpō]. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press. ISBN 4-590-00570-0; ISBN 0-89346-149-0.

- Miller, Roy. (1967). The Japanese language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Miller, Roy. (1980). Origins of the Japanese language: Lectures in Japan during the academic year, 1977-78. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-95766-2.

- Mizutani, Osamu; & Mizutani, Nobuko. (1987). How to be polite in Japanese: 日本語の敬語 [Nihongo no keigo]. Tokyo: Japan Times. ISBN 4-7890-0338-8; ISBN 4-7890-0338-9.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi. (1990). Japanese. In B. Comrie (Ed.), The major languages of east and south-east Asia. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04739-0.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi. (1990). The languages of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36070-6 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-36918-5 (pbk).

- Shibamoto, Janet S. (1985). Japanese women's language. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-640030-X. Graduate Level

- Tsujimura, Natsuko. (1996). An introduction to Japanese linguistics. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19855-5 (hbk); ISBN 0-631-19856-3 (pbk). Upper Level Textbooks

- Tsujimura, Natsuko. (Ed.) (1999). The handbook of Japanese linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20504-7. Readings/Anthologies

|